The Iran Crisis and the Ghosts of the Gulf of Tonkin

John Bolton’s personal history of blatantly attempting to politicize intelligence is reminiscent of a mistake once made by the Johnson administration.

Disturbing similarities between the run-up to the Iraq War of 2003 and the Trump administration’s bellicosity toward Iran keep accumulating. They include war-selling rhetoric seemingly derived from the same script. But in some respects, parallels to the present are even more distinct with an incident that occurred over half a century ago, beyond the living memory of most Americans. The time was August 1964, and the place was the dark nighttime waters of the Gulf of Tonkin.

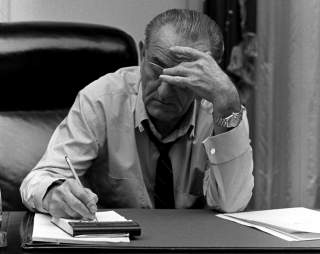

Then, as now, a U.S. administration wanted to show toughness against an Asian country deemed to be an adversary. Lyndon Johnson, who had become president nine months earlier when John Kennedy was assassinated, was facing Barry Goldwater in the coming presidential election. Johnson had to balance his posture as the more peace-loving candidate with evidence that he had the backbone to use force when necessary. In a telephone conversation with his secretary of defense, Robert McNamara, Johnson interpreted the political environment this way as the Tonkin incident began to unfold: “The people that’re calling me up all feel that the Navy responded wonderfully . . . but they want to be damned sure I don’t pull ’em out and run. That’s what all the country wants because Goldwater is raising so much hell about how he’s gonna blow ’em off the moon.”

Then, as now, the United States was deploying its military forces assertively, to the point of brinksmanship, in the backyard of the would-be adversary. U.S. and South Vietnamese naval forces were conducting two operations at the time in the Gulf of Tonkin. One was intelligence-gathering by U.S. warships, including the two destroyers that would be involved in the incident, the Maddox and the Turner Joy. The other was a series of South Vietnamese raids and infiltrations along the North Vietnamese coast. Although the two operations were separate, it is unlikely that the North Vietnamese viewed them that way.

Then, as now, policymakers in the U.S. administration welcomed—even sought—an incident as a rationale for air strikes against the adversary, in the absence of anything else that North Vietnam was doing that was a threat to U.S. interests.

The Non-Attack in the Gulf

There never has been any doubt that on August 2, 1964, North Vietnamese patrol boats fired on the Maddox, which was operating close to North Vietnam’s coast. The Maddox quickly retreated to more distant waters in the gulf. Two days later the now keyed-up crews of the Maddox and Turner Joy reported that they were again under attack, citing radar and sonar signals and the efforts of sailors on deck to make sense of glimmers of light on the dark and wind-swept waters. If an attack on August 4 had actually occurred, then it would have been more significant than the earlier attack because it would indicate North Vietnam had aggressive intentions extending beyond protection of its coast.

Later exhaustive study of the subject has shown that there was no second attack. But the Johnson administration let its preferred conclusion get ahead of the evidence. A prompt press leak about reports of a second attack made it difficult for the administration to hold back on a judgment about the reported incident or a retaliatory military strike without being accused of pusillanimously covering up an attack on U.S. forces. The Pentagon issued a statement that flatly asserted that North Vietnam had attacked the Maddox and the Turner Joy in the open waters of the Gulf of Tonkin.

The search for evidence to back up this assertion was unashamedly tendentious. A message from the Joint Chiefs of Staff on August 6 made the intention explicit: “An urgent requirement exists for proof and evidence of second attack by DRV naval units . . . Material must be of type which will convince United Nations Organization that the attack did in fact occur.”

Intelligence professionals were left with no doubt that the mission was to make a case about North Vietnamese aggression and not to focus on any deficiencies in the evidence. A CIA officer who attended meetings on the subject later recalled, “We knew it was bum dope that we were getting from the Seventh Fleet, but we were told to give only the facts with no elaboration on the nature of the evidence. . . . Everyone knew how volatile LBJ was. He didn’t like to deal in uncertainties.”

Analysts at the National Security Agency who were charged with interpreting ambiguous North Vietnamese communications operated in the same environment. A later study by an in-house NSA historian faulted their work for misinterpreting the few intercepts that became part of the administration’s case and not sending forward a larger amount of material that contradicted the case. The historian observed that “there might have been a lot of pressure on the NSA people to produce ‘proof’ is quite likely.”

The politicization was sufficient to carry the day. Congress passed the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, which became the congressional authorization for U.S. airstrikes against North Vietnamese naval facilities and also for a ground war in which fifty-eight thousand Americans would die.

Possible Reprise in the Persian Gulf

Today, spinning an incident into a rationale for offensive military action is likely to involve not just whether an incident occurred but also who was responsible for whatever did occur. The reported sabotage of oil tankers off the coast of the United Arab Emirates is just one example of the kind of incident that could be spun.

As with Vietnam in 1964, politicians are susceptible to being swept up by a mood of revenge and bellicosity. In the current case, follow-the-leader partisanship will accentuate this tendency among members of the president’s party.

Also as with Vietnam in 1964, politicized interpretation and selection of fragmentary and ambiguous intelligence is likely to be part of the spinning. It was part of it in the selling of the Iraq War in 2002–2003, with the pressure including repeated visits by Vice President Richard Cheney to CIA headquarters to try to get analysts to come up with anything that would support the administration’s mythical “alliance” between Iraq and Al Qaeda. Now National Security Advisor John Bolton is convening meetings at CIA headquarters to discuss Iran. The specific topics for discussion have not been revealed, but given Bolton’s personal history of blatantly attempting to politicize intelligence, a replay of something like the Cheney ploy is likely.

Congress—which, unlike the public, can access classified information—bears the principal responsibility for countering such destructive gambits. The average age of members of the current Congress is fifty-eight in the House and sixty-two in the Senate, meaning that the average member was only a young child at the time of the Gulf of Tonkin incident and probably has no direct memory of it. (Disclosure: being somewhat older, I remember the episode well, and served as an Army officer in the Vietnam War.) Some attention to this unfortunate part of U.S. history might help to avoid an additional painful and destructive chapter in that history.

Paul R. Pillar is a contributing editor at the National Interest and the author of Why America Misunderstands the World.

Image: Reuters