General Chen’s Assurance Not Entirely Reassuring

Soothing words from the PLA leader fail to mask a discomforting reality.

During his high-profile visit to the United States last week, General Chen Bingde, the head of China’s armed forces, emphasized that his country posed no threat to the United States or anyone else. In a speech at the National Defense University in Washington, Chen stated categorically: “The world has no need to worry, let alone fear, China’s growth. China never intends to challenge the U.S.” He added that China’s military is decades behind the U.S. military in capabilities and that Beijing wants to focus on economic development, not a mutually debilitating arms race that China could not win in any case.

During his high-profile visit to the United States last week, General Chen Bingde, the head of China’s armed forces, emphasized that his country posed no threat to the United States or anyone else. In a speech at the National Defense University in Washington, Chen stated categorically: “The world has no need to worry, let alone fear, China’s growth. China never intends to challenge the U.S.” He added that China’s military is decades behind the U.S. military in capabilities and that Beijing wants to focus on economic development, not a mutually debilitating arms race that China could not win in any case.

That was not really a new message. Chinese diplomats and political leaders have offered similar assurances (although usually not quite that bluntly) for years. There were lingering suspicions in U.S. policy circles, though, that the leadership of the People’s Liberation Army was not entirely on board regarding that soothing message. General Chen’s statement seemed designed to allay those suspicions and fears.

The statement was also part of a new charm offensive following a series of actions over the previous year or so that the United States and China’s neighbors considered worrisome, if not evidence of outright belligerent intent. Beijing’s more assertive behavior, especially in East and South Asia, led to some push back, most notably the surprisingly in-depth security discussions between Japan and South Korea that seemed to be directed against China. In recent months, it appeared that Chinese leaders learned the lesson that brusque behavior was counterproductive, and they have reverted to a softer stance. General Chen’s trip and speech is part of that new pattern.

U.S. officials should treat his charm offensive with a certain amount of skepticism. Some aspects of his assurance to the United States are very likely true. Chinese leaders learned from the disastrous experience of the Soviet Union that it was economically suicidal to mount a global military challenge to U.S. preeminence. Beijing has no intention of adopting the same course—at least not for several decades. Not only is Chen correct that the gap in military capabilities between the United States and China is too great for a credible challenge, but the top priority of the leadership in Beijing is to perpetuate vigorous economic growth. Excessive military spending would be a drag on the future of a healthy economy.

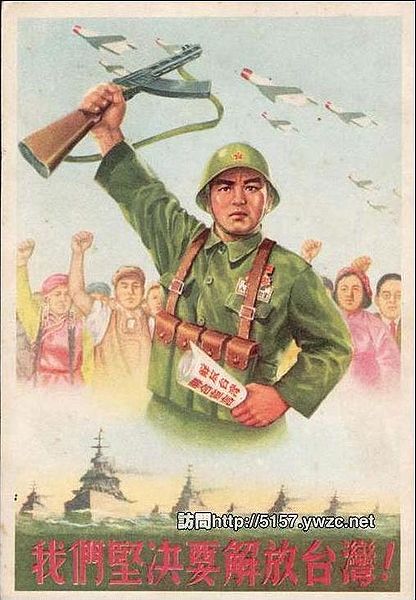

But China’s wise decision not to mount a global military challenge to the United States does not mean that Beijing accepts a continuing U.S. hegemony in East Asia and the western Pacific. Indeed, the focus of the PLA’s modernization effort is on weaponry—from anti-ship missiles, to new submarines, to anti-satellite systems, to cyber warfare capabilities—that is clearly directed against Washington’s ability to intervene in China’s neighborhood. The primary underlying purpose is to deter the United States from intervening on behalf of Taiwan, if a crisis erupted, or failing that, to defeat U.S. forces in a showdown. More broadly, Beijing aims to have the military power to make good on its territorial claims in the East China and South China seas, despite U.S. opposition.

Despite General Chen’s assurance that Beijing has no intention of mounting a global challenge to U.S. power, his country fully intends to mount a regional challenge to U.S. military dominance in East Asia. Indeed, it is already doing so.

U.S. policymakers need to make a sober assessment of the situation and decide if it is worth the cost and risk to try to preserve America’s eroding dominance on China’s eastern oceanic flank. The evidence suggests that within the next decade or two, the cost and risk required to thwart China’s regional strategic objectives will mount to a very high level. General Chen’s soothing words do not change that reality.