Teddy Roosevelt and Taft: The Odd Couple

Mini Teaser: Few American stories of personal fellowship are as poignant as the Roosevelt-Taft friendship—and its brutal disintegration.

Doris Kearns Goodwin, The Bully Pulpit: Theodore Roosevelt, William Howard Taft, and the Golden Age of Journalism (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2013), 928 pp., $40.00.

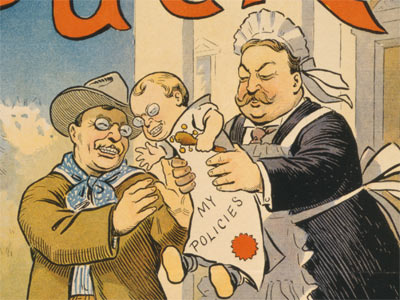

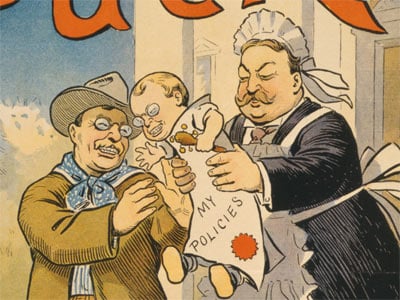

IN THE EARLY 1890s, when Theodore Roosevelt met William Howard Taft during their early stints as government officials in Washington, Roosevelt said, “One loves him at first sight.” Later, as president, Roosevelt extolled the virtues of Taft, then U.S. governor-general of the Philippines: “There is not in this Nation a higher or finer type of public servant than Governor Taft.” After Taft became Roosevelt’s war secretary, the president reported to a friend that the new cabinet chief was “doing excellently, as I knew he would, and is the greatest comfort to me.” Before going on vacation, TR assured the nation that all would be well in Washington because “I have left Taft sitting on the lid.” Subsequently, when Taft expressed embarrassment about a news article unflattering to Roosevelt that had been spawned by a Taft campaign functionary, the president was unmoved. “Good heavens, you beloved individual,” he wrote, suggesting Taft should get used to false characterizations in the press, as he himself had done, although “unlike you I have frequently been myself responsible.”

Such expressions betokened a special relationship between public servants that extended beyond political expediency and touched deep cords of personal affection. For his part, Taft described their friendship as “one of close and sweet intimacy.”

After Taft succeeded Roosevelt as president and sought in his own way to extend the TR legacy, though, the friendship fell apart. Roosevelt, concluding his old chum didn’t measure up, turned on him with a polemical vengeance that negated the mutual affections of old. Going after his former friend, first in an effort to wrest from him the 1912 Republican presidential nomination and then as an independent general-election candidate, Roosevelt destroyed the Taft presidency—and brought down the Republican Party in that year’s canvas. When the Taft forces prevailed in a typical credentials fight at the GOP convention, TR seized upon it as proof of Taft’s mendacity and corruption. “The receiver of stolen goods is no better than the thief,” he declared. When Taft’s political standing began to wane, largely from TR’s own attacks, he dismissed his erstwhile companion as “a dead cock in the pit.” The former president said, “I care nothing for Taft’s personal attitude toward me.”

In the annals of American history, few stories of personal fellowship are as poignant and affecting as the story of the Roosevelt-Taft friendship and its brutal disintegration. But it carries historical significance beyond the shifting personal sentiments of two politicians. This particular story of personalities takes place against the backdrop of the Republican Party’s emotion-laden effort—and the nation’s effort, and these two politicians’ efforts—to grapple with the progressive movement and the pressing contradictions and societal distortions created by industrialization.

Now the distinguished historian Doris Kearns Goodwin scrutinizes the Roosevelt-Taft saga, bringing to it her penchant for presenting history through the prism of personal storytelling. In No Ordinary Time, she illuminated the Franklin Roosevelt presidency by probing the complex and mysterious marriage of Franklin and Eleanor. In Team of Rivals, which examined Abraham Lincoln’s unusual decision to fill his cabinet with his political competitors, she not only laid bare crucial elements of Lincoln’s political temperament but also presented a panoramic survey of his time—and gave currency to a term that now figures prominently in the nation’s political lexicon. And now, with The Bully Pulpit, she deciphers a pivotal time in American politics through the moving tale of TR and Will, girded by her characteristic deft narrative talents and exhaustive research. And there’s a bonus: she weaves into her narrative the story of S. S. McClure’s famous progressive magazine, named after himself and dedicated to the highest standards of expository reporting and lucid writing.

Goodwin’s narrative takes on a particularly powerful drive as the TR-Taft friendship crumbles—and then, after the sands of time have eroded the sharp edges of animus, is restored. The author’s narrative doesn’t bring a strong focus to Roosevelt’s powerful views and actions on foreign policy—his vision of America as preeminent global power, for example, or his dramatic decision to send his Great White Fleet around the world as a display of U.S. naval prowess and a spur to congressional support for his cherished naval buildup. Nor does she trace in elaborate detail the challenging developments in the Philippines, called by TR biographer Kathleen Dalton “the war that would not go away” (although TR finally brought it to a conclusion through a notable level of military brutality directed against insurgent forces). Rather, this is a book about the emergence of the progressive impulse, which sought to apply federal intervention to thwart “the corrupt consolidation of wealth and power” within industrial America. Goodwin clearly believes this counterforce was necessary to protect ordinary Americans from the unchecked machinations of the “selfish rich,” industrial titans, and corrupt local and state governments.

She is correct, of course. The advent of American industrialization had generated substantial economic growth through the latter half of the nineteenth century, and that in turn had fostered the creation of vast new wealth. The Republican Party, as the champion of this development, enjoyed a dominant position in American politics. But the party was beginning to falter at century’s end as it failed to address the attendant problems of the industrial era—predatory monopolies, abuse of the working classes, fraud and malpractice in the distribution of food and medicines. A new turn was necessary, but any suggestion of one antagonized entrenched interests, many within the Republican Party itself. These included industrial plutocrats, their cronies among the urban political bosses and allied members of Congress. A potent political clash was probably inevitable.

ROOSEVELT AND TAFT, born thirteen months apart in the late 1850s, enjoyed comfort and privilege as children. Taft’s father was a prominent Cincinnati lawyer and judge who served as U.S. war secretary and attorney general in the administration of President Ulysses Grant. He was a loving but demanding father who approached life as relentless duty, devoid of anything resembling joy. By contrast, Roosevelt’s father, scion of a family that had amassed a substantial fortune in New York commerce, real estate and banking, took delight in his work but skillfully combined it with a robust social life and exuberant family activities. He was “the most intimate friend of each of his children,” recalled Theodore’s sister, Corinne.

ROOSEVELT AND TAFT, born thirteen months apart in the late 1850s, enjoyed comfort and privilege as children. Taft’s father was a prominent Cincinnati lawyer and judge who served as U.S. war secretary and attorney general in the administration of President Ulysses Grant. He was a loving but demanding father who approached life as relentless duty, devoid of anything resembling joy. By contrast, Roosevelt’s father, scion of a family that had amassed a substantial fortune in New York commerce, real estate and banking, took delight in his work but skillfully combined it with a robust social life and exuberant family activities. He was “the most intimate friend of each of his children,” recalled Theodore’s sister, Corinne.

Both youngsters demonstrated acute intellectual abilities and developed early ambitions to leave a mark on society. Both emerged among their peers as natural leaders to whom others looked for guidance. Both gravitated to the law and to public service and never hankered for private attainment or wealth. Both experienced significant career propulsion at an early age. Both embraced a reformist sensibility dedicated to clean government and opposition to political bossism. Both began their formative years of political consciousness with a mild conservatism of the kind typically found among the privileged, but both later developed an appreciation for elements of the progressive ethos.

There the similarities end. Roosevelt was a man in perpetual motion—restless, forceful, cocky, a “bubbling, explosively exuberant American,” as the Boston Daily Globe put it. A British viscount said he had seen “two tremendous works of nature in America—the Niagara Falls and Mr. Roosevelt.” The writer William Allen White suggested TR’s mind moved “by flashes or whims or sudden impulses.”

Roosevelt’s theatrical self-importance led even his children to acknowledge that he wanted to be “the bride at every wedding and the corpse at every funeral.” His speech sparkled with vivid expressions that reflected his unabashedly held strong opinions. When Supreme Court justice Oliver Wendell Holmes came down on what TR considered the wrong side of an important decision, Roosevelt declared, “I could carve out of a banana a judge with more backbone than that.”

On the other hand, wrote White, Taft’s mind moved “in straight lines and by long, logical habit.” He was easygoing—modest in demeanor, conciliatory by temperament. While Roosevelt garnered attention by putting himself forward with endless quips, asides and pronunciamentos, the more self-conscious Taft let others come to him, and because he stood out as solid and fair-minded they almost always did. White described him as “America incarnate—sham-hating, hardworking, crackling with jokes upon himself, lacking in pomp but never in dignity . . . a great, boyish, wholesome, dauntless, shrewd, sincere, kindly gentleman.”

As the two men made their way in government service, Roosevelt moved amid a constant cloud of controversy. And yet he discovered that his penchant for relentlessly pushing his pet issues to the forefront and forcing decisions could be highly effective. As the youngest member of the New York state legislature, he became one of New York’s leading reform politicians. “I rose like a rocket,” he later explained with characteristic pride.

Taft meanwhile gravitated to the judiciary, which proved compatible with his judicious nature. At the remarkably young age of twenty-nine, he was appointed an Ohio state judge. He distinguished himself sufficiently to win a presidential appointment as U.S. solicitor general in the Benjamin Harrison administration. Thus, he moved with his wife Nellie to Washington and took up residence near Dupont Circle, just a thousand feet from the new residence of Theodore Roosevelt, recently appointed to the Civil Service Commission. The two took to walking together to work each morning.

Pullquote: The country saw the GOP rupture based on atmospherics, brazenly inaccurate accusations, ideological fervor and personal whims writ large. It was the politics of temper tantrum.Image: Essay Types: Book Review

Essay Types: Book Review