Are Sanctions a Fatwa on Iran?

The sanctions are not about Iran's nuclear program. They are aimed at regime change.

New Year's Day saw rhetorical fireworks fly over the straits of Hormuz. A large Iranian military exercise in the Gulf coincided with threats to close the waterway if sanctions are imposed on Iran's oil sector. More than 15 million barrels of crude transit the twenty-one-mile-wide choke point daily, constituting about 35 percent of the worldwide tanker oil shipments. Iran's defiance has been increasing in proportion to the number and severity of the sanctions imposed. So why aren't the sanctions working?

New Year's Day saw rhetorical fireworks fly over the straits of Hormuz. A large Iranian military exercise in the Gulf coincided with threats to close the waterway if sanctions are imposed on Iran's oil sector. More than 15 million barrels of crude transit the twenty-one-mile-wide choke point daily, constituting about 35 percent of the worldwide tanker oil shipments. Iran's defiance has been increasing in proportion to the number and severity of the sanctions imposed. So why aren't the sanctions working?

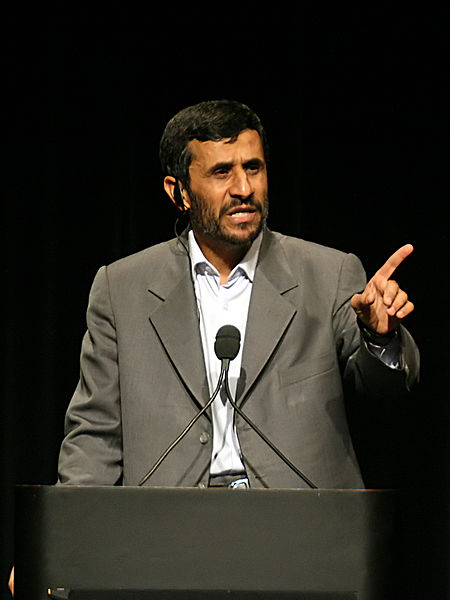

Ostensibly, sanctions have been imposed because Iran is not providing the level of transparency the United States and its allies desire of Iran's nuclear program. The nuclear-related sanctions against Iran date from 2006—all imposed during the tenure of President Ahmedinejad. Besides the multiple unilateral U.S. sanctions, there are also four UN Security Council resolutions: 1737 (imposed in 2006), 1747 (2007), 1803 (2008) and 1929 (2010). The EU and other countries, including Canada, Australia, Japan, South Korea, Israel and India, have each slapped on their own sanctions as well. With all this economic pressure, why won't Tehran cooperate with the West and allow more intrusive inspections of its nuclear facilities?

The reason is simple: the sanctions are not about Iran's nuclear program. They are aimed at regime change.

Conditions for lifting the sanctions go way beyond anything having to do with Iran’s alleged nuclear-weapons program. No matter what Iran does with its nuclear program, they will remain in place. The situation may—intentionally or not—become a prelude to war.

For instance, the U.S. sanctions can only be lifted after the president certifies to Congress

that the government of Iran has: (1) released all political prisoners and detainees; (2) ceased its practices of violence and abuse of Iranian citizens engaging in peaceful political activity; (3) conducted a transparent investigation into the killings and abuse of peaceful political activists in Iran and prosecuted those responsible; and (4) made progress toward establishing an independent judiciary.

Just in case those conditions are insufficiently implausible, the president has to certify further that "the government of Iran has ceased supporting acts of international terrorism and no longer satisfies certain requirements for designation as a state sponsor of terrorism; and [that] Iran has ceased the pursuit, acquisition, and development of nuclear, biological, chemical, and ballistic weapons."

Many U.S. allies, such as Bahrain and Saudi Arabia, could not satisfy all these conditions. So even if Tehran were to stop all uranium enrichment and dump all of Iran’s centrifuges into the Gulf and shutter its nuclear program entirely, Iran would still be sanctioned by the U.S. Congress.

The UN Security Council sanctions have only marginally less impossible goals than the unilateral US ones. While the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) would be happy to simply see slightly more transparency regarding Iran’s nuclear program, nothing short of stopping all uranium enrichment will satisfy the arbitrary conditions of the UN sanctions. The Security Council has "affirmed that it would suspend the sanctions if, and so long as, Iran suspended all enrichment-related and reprocessing activities, as verified by the International Atomic Energy Agency."

This is clearly something that will not happen since virtually all the Iranian polity and people support their sovereign right to enrich uranium, just as Argentina, Brazil, China, France, Germany, India, Israel, Japan, the Netherlands, Pakistan, Russia, the United Kingdom and the United States do.

So while the IAEA initially referred Iran to the UN Security Council over a lack of transparency, the Security Council took that opportunity to slap on additional ad hoc demands: this is like being stopped for a traffic violation and then having your car confiscated for no solid reason. While Iran is probably willing and able to satisfy IAEA demands for greater transparency, such a concession will not satisfy the Security Council demands that require Iran to suspend enrichment indefinitely.

This is possibly why Iran feels it has little to gain by cooperating with the IAEA at this stage. Even if it makes the IAEA happy, the Security Council sanctions and various others would still be fully in effect. So these sanctions are, in fact, a disincentive for Iran to cooperate with the IAEA; if they are going to be sanctioned by the Security Council, the United States and the EU anyway, why should they cooperate with the IAEA?

Further poisoning the waters is the questionable legality of the UN sanctions themselves. Such sanctions are applicable under Chapter 7 of the UN Charter—but only after a determination of "the existence of any threat to the peace, breach of the peace, or act of aggression" is found, something which has never been done in Iran’s case.

The obsession with Iran's nuclear program becomes even more puzzling when viewed in the context of statements from knowledgeable experts. Mohamed El-Baradei, the Nobel Peace Prize recipient who spent more than a decade as the director of the IAEA, recently told investigative journalist Seymour Hersh that he had not "seen a shred of evidence that Iran has been weaponizing, in terms of building nuclear-weapons facilities and using enriched materials. . . . I don’t believe Iran is a clear and present danger. All I see is the hype about the threat posed by Iran."

The U.S. director of national intelligence James Clapper released a new National Intelligence Estimate (NIE) on Iran's nuclear program in 2011. This document represents the consensus view of sixteen U.S. intelligence agencies. Although the content of the new NIE is classified, Clapper confirmed in senate questioning that he has a "high level of confidence" that Iran "has not made a decision as of this point to restart its nuclear weapons program."

The latest (and much ballyhooed) IAEA report on Iran's nuclear program backs this up. The report states that the weapons-research program “was stopped rather abruptly pursuant to a ‘halt order’ instruction issued in late 2003” and that “the agency’s ability to construct an equally good understanding of activities in Iran after the end of 2003 is reduced, due to the more limited information available.”

Recently, Defense Secretary Leon Panetta weighed in: “Are they trying to develop a nuclear weapon? No. But we know that they’re trying to develop a nuclear capability. And that’s what concerns us.”

The most objective reading of Iran’s intentions is that it may be stockpiling enough low-enriched uranium (LEU) to give itself a "break-out" option to weaponize in the future. Unfortunately for the U.S. government and its allies, there is nothing illegal about that. (Note that even the 20 percent enriched uranium is considered LEU by the IAEA). Options and ambitions that the Iranian leadership may harbor in their heads cannot be illegal. To be clear: The fault lies with the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, which allows a latent nuclear-weapons capability, not with Iran which is simply taking advantage of this fact.

But what if Iran does cheat at the last moment and races to the bomb? The U.S. National Defense University looked into this "nightmare scenario" in 2005 (when it was thought Iran did have a nuclear-weapons program) and concluded that its view, "and nearly all experts consulted agree, [was] that Iran would not, as a matter of state policy, give up its control of such weapons to terrorist organizations and risk direct US or Israeli retribution." The study also stated that the "United States has options short of war that it could employ to deter a nuclear-armed Iran and dissuade further proliferation." It ventured that Iran may have desired nuclear weapons in the past because it felt strategically isolated and that "possession of such weapons would give the regime legitimacy, respectability, and protection." That is, for deterrence, not aggression. Indeed, there is no reason to believe that the Iranian regime is suicidal and would kick off a nuclear war with the United States or Israel.

In light of these facts, the UN, United States, European Union and other countries should reevaluate what they hope to accomplish with their increasingly tough sanctions policies. If they want cooperation on the nuclear issue, they should reword the sanctions to clarify that point. If, instead, they are meant as fatwas against the current regime in Iran—as the current wording of the sanctions suggests—we should all prepare for the sequel of the Iraq War, but this time with skyrocketing gas prices and the likelihood of a regional conflagration. It is likely that further “crippling” sanctions will actually encourage Iran to weaponize.

Currently, the sanctions are not directed at Iran’s nuclear program and, in fact, would remain in place even if that nuclear program disappeared overnight. But their dysfunctional nature and inherent opacity may be seen by some Congressional hawks as a benefit. As with Iraq a decade ago, they could say that sanctions have not "worked" and thus justify moving on to the next, and last, resort—war.

Yousaf Butt, a nuclear physicist, serves as a scientific consultant for the Federation of American Scientists. The views expressed are his own.

Image: Daniella Zalcman