A Bad Plan for Obama

The New York Times' proposal for the president's second-term foreign policy combines wooly-headed idealism with half-baked ideas.

After the election, the New York Times editorial board laid out a foreign-policy agenda for President Obama to follow over the next four years. It combines wooly-headed idealism with half-baked thinking.

After the election, the New York Times editorial board laid out a foreign-policy agenda for President Obama to follow over the next four years. It combines wooly-headed idealism with half-baked thinking.

The leading suggestion—which is dedicated much more text than any other—is to aim for a world free of nuclear weapons. Yet zero is the wrong number, because if any one nation hides a few nukes, it would lord over those who do live up to their disarming commitments. One can surely dial down the numbers, but a low level of mutual deterrence is unavoidable—and history shows it works. Moreover, there is no reason to believe that further cuts by the United States and Russia, which the Times holds the president should lead with, will inspire other nations to follow suit. The focus instead ought to be on the hot spots like Iran and especially Pakistan, which is accelerating its production of nuclear arms and which is the most likely place terrorists can get them one way or another.

As to Iran, the Times sees danger in the partisan posturing that occurred during the election. It calls for direct negotiations between Washington and Tehran and believes that sanctions will work. The possibility that they do not is not something the Times’ desk-bound strategists feel they need to consider. They have nothing to say about the merit of keeping the military option on the table to help Iran see the light.

The Times correctly points out that Al-Qaeda is spreading in North Africa and in Pakistan. Ergo? “Dealing with that challenge will likely become harder, as will the choices Mr. Obama must make. For one thing, he will have to examine whether the expanding use of drones is the right approach.” To call for more examination is always a good idea, but—like appointing commissions, study groups and impact evaluations—most of the time it is nothing but a cop out for those who have no idea where to go next.

The most naïve part of the Times agenda is the suggestion that the president should help the Arab Spring countries “to build their economies quickly” and calibrate this help according to each nation’s progress on human rights and democratization. First of all, the president ran on the promise to focus on nation building at home, not overseas. Second, we have shown surprisingly little capacity to quickly rebuild our own economy; why then would anyone believe that we can do so in the Middle East—where conditions are much less favorable? (This is in all the countries that have no gushing oil wells; those that do—Iraq and Libya—can pay their own way and some). Third, the very term Arab Spring is part of the liberal illusion complex. Most Arab countries either maintain some form of authoritarian regime (Saudi Arabia, the Emirates, Bahrain, Algeria, Morocco and Jordan, among others) or are in turmoil (as in Libya, Syria and Lebanon). The jury is out for Egypt—which I predict will end up with a new strongman (or general) in power—as well as for Tunisia. The notion that the United States can pressure all these nations to democratize and respect human rights is a lovely dream, but dreams do not make a foreign policy.

The Times states that “Mr. Obama is expected to use his second term to deepen engagement with Asia to protect American military interests and ensure American access to economic opportunities in that region. This could be a challenge given the coming change of leadership in Beijing.” These fuzzy lines blur the main issue the “pivot” to the Far East faces. Is it really time to pivot from the Near East—where all the hot spots are, and from which practically all the current threats to U.S. core interests emanate—to the Far East? And if the time for the pivot has come, should the United States seek to partner with China (as Henry Kissinger, Zbigniew Brzezinski, and Hugh White recommend)? Or should Washington seek to contain China, by positioning more military forces in the area, forming more military treaties, and conducting more military exercises? The latter option may lead to an arms race with China in space and the cyber world.

I am not saying that the Times agenda is without any merit. If the list it provides is turned on its head, the president may do well over the next four years: The Obama administration should focus in the near term on the Middle East. The first priority must be dealing with the nukes there rather than those of Russia. We must limit our ambition to protecting our security and that of our allies, and refrain from nation building overseas. Only then can we restore our economy and thus be able to discharge our international responsibilties.

Amitai Etzioni served as a senior advisor to the Carter White House; taught at Columbia University, Harvard and The University of California at Berkeley; and is a university professor and professor of international relations at The George Washington University. His latest book is Hot Spots: American Foreign Policy in a Post-Human-Rights World (Transaction, 2012).

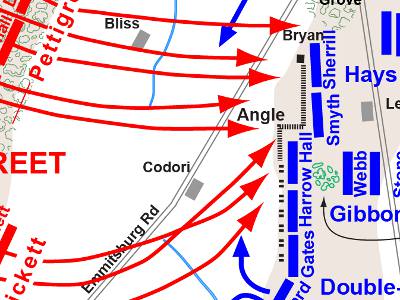

Map by Hal Jespersen, www.posix.com/CW.