Diminishing Nixon

Rather than think about the Nixon Library and the new Watergate exhibit as weapons in a political war, we should let Nixon be Nixon.

“No event in American history,” Richard Nixon once wrote, “is more misunderstood than the Vietnam War. It was misreported then, and it is misremembered now.”

“No event in American history,” Richard Nixon once wrote, “is more misunderstood than the Vietnam War. It was misreported then, and it is misremembered now.”

With a generous heart, one could say pretty much the same thing about Richard Nixon himself. He was misunderstood, misreported and misremembered. He was, in fact, a great president, many of his friends—and a few others—still believe. Who better in foreign affairs, for example? A mistake or two, yes, but who hasn’t made one? Moreover, Watergate was a contrived conspiracy, according to some of his supporters, a concoction of the liberal media, which “accused and vilified” the president and his “pals.”

“So unfair,” lamented blogger Anne Walker, wife of Chairman Ron Walker of the Nixon Foundation. The pals were “convicted of perjury, not wrongdoing,” she wrote, with apparent seriousness, and “end[ed] up in prison.”

Unlike most other presidents, Richard Nixon seems never able to rest in peace. Apparently, not even at the Nixon Library. Recently, a new Watergate Exhibit was opened, and predictably the Walkers were outraged. According to Mrs. Walker, who was in attendance, the current Director, Timothy Naftali, in his introductory remarks, never “missed using one accusatory buzz word” after another: “abuse of power,” “dirty tricks,” “whitewash,” and “cover up.” Naftali was even asked whether Nixon was anti-semitic, and, lo and behold, noted Mrs. Walker, a “very few days later, several news stories contained newly released quotes on that very subject.” She had hoped that the new exhibit would be “fair and balanced,” (a description familiar to any Fox viewer), but “it did not come out that way.”

The Walkers, whose views reflect the prevailing attitude of the Nixon Foundation, believe that a presidential library—indeed, this presidential library—should project a positive, uplifting image of the president and under no circumstances wallow in his occasional misdeeds, i.e., Watergate. Anne and Ron Walker have been loyal to the Nixon legend for decades. Ron was head of Nixon’s advance team at the White House. Sharing his loyalist views are other former staffers, now gathered around the Nixon Foundation: Larry Higby, who was Bob Haldeman’s deputy, and Dwight Chapin, who was deputy assistant to Nixon, among others.

At this time of national uncertainty, they are all pledged to a common goal. They seek a national resurrection of Nixonian values, a revival of a strong, conservative America, and they see the Nixon Library as the best place to glorify their vision of the new, new Nixon. Because the Nixon Foundation continues to provide much of the Nixon Library’s budget, it assumes the Library should reflect its views of the Nixon presidency.

But herein lies the problem, and it is not one just of definition. It is rather one of historical approach, of honesty with the public, of respect for facts. Presidential libraries are not supposed to be flagships of political reinvention, budgetary contributions notwithstanding. They are supposed to be—and most are—historically rooted, philosophically neutral representations of our presidents. Each is a history lesson, a look inside the White House, for waves of American visitors, and others.

Fortunately, the Walker vision of the Nixon Library is not shared by all those associated now, or in the past, with the Nixon Foundation. John Taylor, a former executive director of the Foundation, appears to take a different view, implicitly endorsing comments by historian Robert K. C. Johnson on his blog. Johnson states that Mrs. Walker’s “contentions are ludicrous.” He believes that a “best case scenario” for a presidential library would be the LBJ Library. Lady Bird Johnson and Harry McPherson were both “committed to preserving Lyndon Johnson’s legacy,” but, stresses Johnson, “through honesty with the public and ensuring that scholars had full access to the available documents.”

In Johnson’s blunt judgment, the Walker approach “clearly represents the other extreme.” It may, in fact, at day’s end, diminish Nixon’s stature. Johnson writes that Mrs. Walker “wildly portrays” Naftali as “coordinating a conspiracy designed to spread in the media unflattering (but accurate) quotes from Nixon.” Then, he adds, playfully, “It could be said, I suppose, that Nixon’s associates have unusual expertise on the issue of conspiracies.”

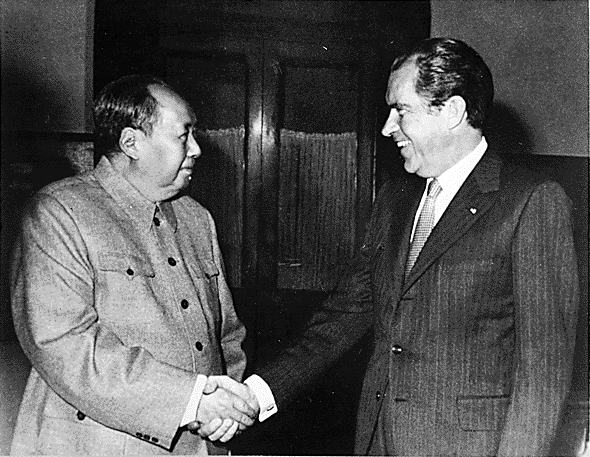

Indeed, during their time in office, they did see conspiracies around every corner and critics as enemies of their secretive style of governance. They engaged in illegal wiretapping of officials and journalists. They misused the CIA. They established an “enemies list.” They lied to Congress and to the American people. And while it is true that Nixon masterfully managed foreign policy during dangerous times in the Cold War, it is also true that he is the only president forced to retire from office, one step ahead of almost certain impeachment.

Rather than think about the Nixon Library as a weapon in a political war, the Walkers might try to let Nixon be Nixon, blemishes and all, and then have faith in the library visitor to reach a “fair and balanced” judgment of Richard Nixon’s place in American history.

Correction: April 18, 2011

The original version of this article incorrectly attributed quotes about Mrs. Walker’s opinions on the LBJ Library and Naftali to John Taylor. Robert KC Johnson in fact made the statements, and the piece has been updated to reflect that.