Libya: The Lost War

Tribal warfare. Chaos, bloodshed and pseudo-democracy. Emboldened tyrants from Tehran to Pyongyang. And that's if we win.

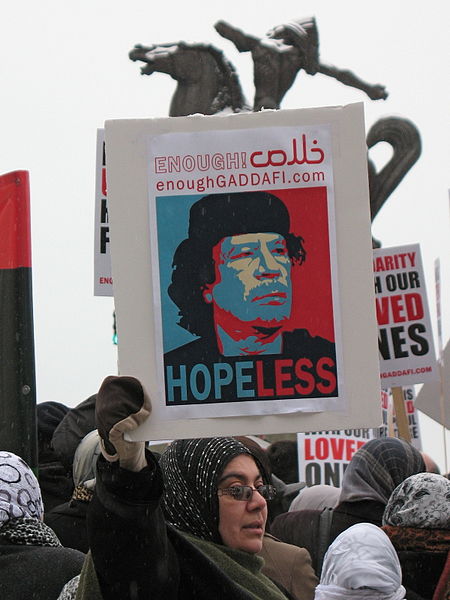

At one hundred days since the United States-led intervention in Libya began, one can draw several key lessons from this operation. Despite the fact that I predict that the stalemate will not last, and Qaddafi will either be killed or quit, there are several strong reasons to conclude that the mission has already failed, including, of course, that it is still ongoing.

At one hundred days since the United States-led intervention in Libya began, one can draw several key lessons from this operation. Despite the fact that I predict that the stalemate will not last, and Qaddafi will either be killed or quit, there are several strong reasons to conclude that the mission has already failed, including, of course, that it is still ongoing.

For one thing, the intervention emboldens Iran. The Obama administration has declared repeatedly that it is “unacceptable” for Iran to obtain nuclear weapons. The same statement was made by the previous White House and endorsed by our European allies. Moreover, the U.S. government has repeatedly stated that “all options are on the table,” the phrase used to threaten military action. WikiLeaks make it clear that defanging Iran is viewed by our main allies in the Middle East as vital to their interests.

Despite these bipartisan, multilateral declarations, the leaders of Iran cannot but conclude that a nation that gives up its program of obtaining of WMDs—as Qaddafi’s Libya did—is much more vulnerable to Western intervention than a nation that succeeds in acquiring them, as North Korea did, and furthermore, that the Western alliance has a hard time dealing with military forces much less impressive than those of Iran. NATO forces, in Secretary Gates’ words, are so weak they face “collective military irrelevance.” At the same time, the United States, already mired in three wars in the Muslim world and desperately looking for ways to cut its deficit, has shown that it would rather have others doing the intervening and has no stomach for another war. To return to Secretary Gates’ candid observations, he urged us to avoid wars of choice and engage only when our vital interests are threatened. And many observers in Europe and the U.S. have already pointed out that Iran is so far not threatening any of our true national interests. All this suggests that Iran cannot but be much emboldened. Other tyrants and autocrats, such as those who govern North Korea and Myanmar, are surely also taking note.

Much has already been made, for good reason, of the confused rationale for the Libya intervention, the inconsistency with which it is applied (especially with regards to nonintervention in Syria), and the mission creep (from humanitarian intervention to regime change). One must now add a major concern: although Qaddafi will be unseated, the result will not be a government that will protect human rights, as Secretary of State Hillary Clinton so eloquently held up as what is required. One cannot foresee at this point how long inter-tribal conflicts will last after Qaddafi is gone, what role the Libyan military will play in the new regime, or what kind of government the rebels—who have already formed death squads of their own—will form. However, we know that Libya has few of the foundations of a liberal democracy: it has a weak civil society, a thin middle class and no democratic tradition to revive. If this unhappy prediction holds true, five or ten years from now, when one looks at the Libya intervention, it will not be the overthrow of a tyrant to make for a liberal democratic regime. It will be God knows what kind of mishmash of chaos, bloodshed, and pseudo-democracy.

While Western officials will surely try to put the best face possible on this regime change, neutral observers will see here one more reason to limit future interventions to either those that are strictly humanitarian interventions (a la Kosovo) those that truly serve our vital national interests (say, if Iran were foolish enough to close the Strait of Hormuz).

One reason the Libyan intervention initially seemed politically attractive was because humanitarian interventions have an appeal both to many liberals (who are rather disappointed in the doings of the Obama administration) and to many conservatives, led by John McCain (who believe in a muscular U.S. out to unseat tyrants). One hopes that both camps will draw on the lessons of the Libya intervention and realize that whether we are driven by idealism (to help others) or arrogance (that we can help others)—our power (that of our allies included) to do good is limited, and the less often we jump in, and the more limited the mission and the more we guard against mission creep, the more good we shall do.