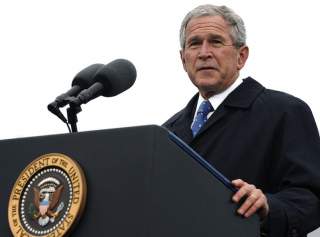

Bush, the Torture Report and the Issue of Accountability

One way to protect the reputation of America: respecting the rule of law that we preach to the rest of the world and giving ourselves the credibility to rally world opinion in condemning enemies who engage in barbaric practices.

While it is appropriate to criticize the Central Intelligence Agency for its practice of torture and for its false claims about the intelligence it derived from torture, the Agency's misdeeds should not obscure the ultimate responsibility for these horrifying practices of former president George W. Bush. Perhaps some information was kept from President Bush and perhaps some CIA officials lied to him about their practices. That does not mitigate his responsibility. To the degree he was ignorant, it was willful ignorance. The practices of the CIA did not contradict the policies he approved. They were the foreseeable results of those policies. By maintaining that the CIA's treatment of detainees was lawful and humane, he fended off examination of its conduct as it was taking place.

Under both international law and the law of the United States, a commander is responsible for war crimes when three conditions are met: when he knows, or has reason to know, about the crimes that are committed; when he is in control of those committing those crimes; and when he does not take all feasible measures to prevent and punish the commission of those crimes.

It is clear that President Bush did nothing to prevent torture or punish those who tortured. He did not even acknowledge that the practices of the CIA constituted torture. This left him unable to do anything about its practices. It is also clear that he had control over the Central Intelligence Agency. He and his closest associates have insisted that it did not act unilaterally. As for knowledge of the abuse of detainees, he certainly had reason to know what was going on. Following World War II, the United States executed a Japanese general, Tomoyuki Yamashita, who had reason to know of the crimes committed by his forces in the Philippines, after the U.S. Supreme Court upheld his conviction by a U.S. military tribunal. Though General Yamashita did not specifically direct the commission of the crimes by his troops, like President Bush, he did not exercise due diligence to prevent those crimes.

The Bush administration liked to refer to "the war against terror." One reason it favored a war metaphor was that it seemed to buttress the president's claim that he was exercising his powers as commander-in-chief in dealing with terrorism. Aided and abetted by Vice President Cheney, this provided an argument for resisting intervention by Congress and the courts with the president's exclusive power to fight terrorism. President Bush's insistence that he acted in accordance with his constitutional power as commander-in-chief underscores his need to accept command responsibility.

It should be clear, of course, that President Bush's culpability for torture does not diminish the responsibility of all other officials who administered torture, or who aided or abetted or covered up the practice. Whether they were CIA agents, White House aides, Justice Department lawyers or Department of Defense medical personnel, they should be held accountable. Experience in many other countries in a wide array of circumstances makes it evident that accountability is difficult. At the same time, it is apparent that unless a good faith attempt is made to punish those with the highest level of responsibility for serious abuses, the chances that those abuses will be repeated are very great.

One of the arguments against making public the Senate Intelligence Committee report on the role of the Bush administration and the Central Intelligence Agency in the practice of torture was that it would exacerbate the danger to American personnel at a time when the United States is engaged in conflict with Islamic militants in several parts of the world. That is a legitimate concern, but it cannot be a basis for a continued effort to cover up such abuses. As we should know by now, whether the United States acknowledges its own misdeeds is not the central factor in creating awareness of its practices.

The best way to protect the good name of the United States is not with cover-ups, which don't work; it is by practicing the respect for the rule of law that we preach to the rest of the world and by giving ourselves the credibility to rally world opinion in condemning enemies who engage in barbaric practices. We will not succeed by pretending that our side did not engage in abuses; we have a better chance of succeeding if we demonstrate our own readiness to expose those abuses and to take action to prevent their repetition.

Aryeh Neier is president emeritus of the Open Society Foundations.