Can China Really Ignore International Law?

History shows that small countries can get the upper hand in the end.

In a recent essay, eminent political scientist Graham Allison downplays international criticism of China’s blatant rejection of an unfavorable legal verdict at The Hague. By pointing out the unlawful behavior of status quo powers, his article gives the misleading impression that China’s noncompliance to the international court’s decision is essentially normal.

“[N]one of the five permanent members of the UN Security Council have ever accepted any international court’s ruling when (in their view) it infringed their sovereignty or national security interests,” Allison argues. “Thus, when China rejects the Court’s decision in this case, it will be doing just what the other great powers have repeatedly done for decades.”

Allison also fell short of mentioning some key facts as far as great powers’ compliance with international arbitration is concerned. For instance, it was not the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) that decided on the Philippines’ complaint against China, but an Arbitral Tribunal constituted under Article 287, Annex VII of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). The PCA only serves as a registry.

Such seemingly minute legal facts inform the nature and implications of the Philippines’ landmark lawfare against China. Crucially, Allison didn’t mention that there have been encouraging instances whereby major powers rejected arbitration, and subsequently an unfavorable verdict, but still ended up complying with it anyway. After all, even for great powers, which aspire to leadership and seek respect and predictability in the international system, ignoring international arbitration carries immense costs.

More Than Meets the Eye

In an authoritative article for The European Journal of International Law, legal scholar Aloysius P. Llamzon (2008) shows that “through complex mechanisms of authority signal and the political inertia induced by [international court] decisions, almost all of the [International Court of Justice] decisions have achieved substantial, albeit imperfect, compliance.”

Keep in mind: the International Court of Justice (ICJ) oversees extremely delicate, if not seemingly intractable, cases such as territorial sovereignty. Take for example, the 1986 Nicaragua vs. the United States case filed before the International Court of Justice. At first, America took a hardline position, arrogantly refusing to participate in the arbitration proceedings at all. Similar to China, it also dismissed the unfavorable verdict. Nicaragua, however, relentlessly stepped up international pressure on America by rallying developing world support behind it. The U.S. refused to pay $370.2 million in damages, but after years of successful Nicaragua-led diplomatic pressure, Washington ended up compensating its Latin American neighbor by offering an even larger development aid package during the Victoria Chamorro administration.

True, the United States continues to alienate allies and undermine its moral authority by failing to ratify UNCLOS. And it is high time for belligerent elements within the U.S. Senate to change course. But the U.S. government, as a signatory, has actually complied with the relevant provisions of UNCLOS as a matter of customary international law.

This was more than evident when Washington allowed Chinese warships to pass through America’s two-hundred-nautical-mile Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) in the Pacific, while magnanimously respecting Chinese warships’ right to innocent passage within America’s territorial sea in the shores of Alaska.

In contrast, China, which has ratified UNCLOS, has consistently refused to reciprocate America’s operational observance of prevailing international law, placing restrictions on the movement of foreign military assets well beyond its territorial sea and contiguous zone. Chinese harassment of America’s lawful reconnaissance missions and warships operating in international waters has increased over the years.

China has also rattled most of its neighbors by claiming “historic rights” over adjacent waters such as the South China Sea. In fact, as the Hague verdict makes clear, China has violated the rights of countries such as the Philippines to exploit natural resources within their EEZ. Its massive reclamation activities, almost two dozen times more than that of all other claimant countries combined, has also caused severe ecological damage, the tribunal at The Hague ruled.

Light at the End of the Tunnel

One factor that explains broad compliance with international arbitration, even among great powers, is the concern over reputational cost and long-term consequences of ignoring international law, which is crucial to securing a rule-based global order. This may explain why even an increasingly aggressive Russia, which recently occupied Crimea and has adopted a belligerent position in its “near abroad,” also eventually complied, albeit informally, with the verdict of an arbitration proceeding, which it rejected from the onset.

In the “Arctic Sunrise” case, the Kingdom of Netherlands successfully filed a case at the International Tribunal on the Law of the Sea (ITLOS), complaining that Russia unlawfully placed environmental activists aboard a Greenpeace vessel under detention. Eventually, the Russian legislature approved the release of the crew and the vessel, despite Moscow’s official rejection of the verdict. In short, there was informal compliance.

In South Asia, regional powerhouse India also initially adopted an uncompromising position vis-à-vis its maritime borders with Bangladesh, which took the case to international court despite New Delhi’s opposition. The Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) favored Bangladesh in its final award at the Bay of Bengal, and India complied. The key to ensuring compliance is concerted international pressure, especially when one speaks of a hubristic status quo power (America during Cold War) or assertive revisionist power (China).

This is precisely why it is paramount for China’s neighbors, including Japan, South Korea, India, Australia and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) to consistently push for compliance and encourage China to align its claims with prevailing international law, not obscurely concocted doctrines purportedly based on “historic rights,” lousy cartography and premodern historiography.

Based on the Hague verdict, concerned naval powers, through Freedom of Navigation Operations can utilize the arbitration verdict to challenge China’s baseless sovereignty claims in the Spratlys over low-tide-elevations, which were artificially transformed into islands. If China continues to refuse compliance, the Philippines (and other claimant states) can ask the International Seabed Authority, constituted under the UNCLOS, to revoke China’s license to extract seabed resources in international waters.

Since the Hague verdict clearly states that there are no overlapping EEZs between China and the Philippines, Manila also has the option of filing additional legal complaints if Chinese energy companies unilaterally drill within its EEZ. Not to mention, Vietnam, Malaysia, Japan and Indonesia can also file similar compulsory arbitration cases against China. In short, there will be huge costs if China doesn’t recalibrate its maritime posturing.

So far, it seems that China has successfully tamed its smaller and divided neighbors in Southeast Asia, including the Philippines, but major Asia-Pacific powers such as Japan, South Korea, Australia, India and America have been more forthcoming in their call for compliance with international law and legally binding court verdicts. As the supposed anchor of the Asia-Pacific order, the United States shouldn’t only ratify the UNCLOS, to gain moral ascendancy, but also lead a coalition of law-abiding countries to ensure China operates within the boundaries of prevailing international law. No less than the future of the Asian and the broader global liberal order are at stake.

Richard Javad Heydarian teaches political science at De La Salle University, and formerly served a policy adviser at the Philippine House of Representatives (2009-2015). The Manila Bulletin, a leading national daily, has described him as one of the Philippines’ “foremost foreign policy and economic analysts.” He is the author of Asia’s New Battlefield: The US, China, and the Struggle for Western Pacific (Zed, London). Follow him @Richeydarian.

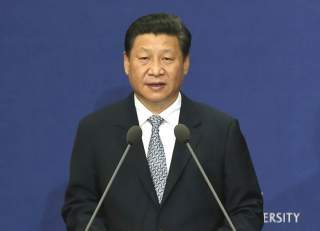

Image: President Xi Jinping at Seoul National University. Flickr/Republic of Korea.