China's Big Course Correction in the South China Sea?

"Washington should at least explore whether a serious rapprochement with China can be pursued."

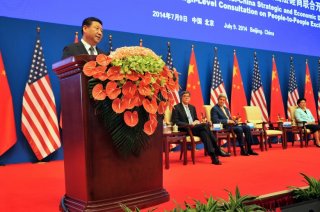

After many months of taking increasingly bold actions at the expense of its neighbors in East Asia, there are recent indications that Beijing may be adopting more conciliatory policies. China has unexpectedly removed a controversial oil-drilling rig that it had deployed in waters near Vietnam. In late June, Chinese president Xi Jinping conducted a high-profile summit meeting with South Korean president Park Geun-hye, seeking to improve relations with that country following last year’s tensions over Beijing’s proclamation of a new air-defense identification zone (ADIZ) in the East China Sea. Even the tone of China’s boilerplate warnings to the United States to stay out of the territorial disputes in the South China Sea has become somewhat more muted. Instead of shrill accusations of U.S. meddling, Chinese officials now urge Washington to be “fair” in its assessment of the issues at stake.

It is possible that the emergence of a more conciliatory stance may only be a temporary, purely tactical shift. But there is also a more encouraging alternative explanation. Beijing may finally have realized that it overreached in pressing its claims in the region, and that its behavior was provoking its neighbors to become more receptive to a U.S.-orchestrated containment policy directed against China. Given its own multitude of geostrategic headaches elsewhere in the world, Washington should at least explore whether a serious rapprochement with China can be pursued.

There is certainly enough evidence of rising anger among East Asian countries regarding China’s conduct over the past three or four years, and only the most obtuse Chinese officials could be unaware of the warning signs. The most obvious, and from Beijing’s standpoint, the most worrisome, development has been Japan’s growing assertiveness on security issues. Tokyo’s “reinterpretation” of Article 9 of the Japanese constitution to allow the country’s participation in collective-defense measures is a watershed event, but there have been other, more subtle changes. In June, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe stated that his government would support Vietnam and other nations that have territorial disputes with China. A few months earlier, Japan had joined with the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) to explore efforts to better secure navigation rights—a clear slap at China’s expansive territorial claims in the South China Sea.

Japan’s new approach clearly envisions a growing array of security partnerships. Tokyo and Canberra negotiated a deal to sell Japanese submarine technology to Australia. Likewise, Japan let it be known that it would consider providing naval patrol vessels to Vietnam, although because of Tokyo’s own tensions with China, the transfer might require some time. Security relations between Japan and India are at a point where respected scholars are now speaking of the possible emergence of a Japanese-Indian alliance.

But Beijing’s worries are not confined to Tokyo’s expanding initiatives in the security arena. China’s smaller neighbors are reacting to what they see as China’s increasingly aggressive behavior. Vietnam and the Philippines have noticeably increased their diplomatic and military cooperation. South Korea agreed to transfer a naval vessel to the Philippines navy in late June. Indonesia is shifting more of its military focus to deal with contingencies in Southeast Asia, implicitly because of growing concerns about China’s ambitions. Despite the extensive and mutually beneficial bilateral economic ties, Australia issued a pointed warning to China that its actions in the South China Sea were unhelpful and provocative. Shortly thereafter, Canberra agreed to a $11.6 billion purchase of 58 F-35 fighters from the United States—a major upgrade of the country’s air force.

It would not be surprising if more astute Chinese officials became alarmed at the surge of anti-China measures among its neighbors. Beijing’s abrasive behavior had reached the point of creating a self-fulfilling prophecy: widespread support for a policy led by the United States and Japan to contain China’s power in the region. Prudence would dictate a course correction and the adoption of a more conciliatory, circumspect approach on Beijing’s part.

That move also creates an opportunity for the United States to dampen the growing animosity in Sino-American relations and to help reduce overall tensions in East Asia. Such a prospect should be sufficient incentive by itself to prod U.S. officials to explore whether China’s recent, more accommodating behavior is genuine. But there are additional incentives. Washington’s geopolitical plate is overflowing with problems and crises, including the chaotic violence in Syria, Iraq, Libya and Ukraine, as well as the drug war-induced turmoil in Mexico and Central America. Especially alarming is that the relationship with Vladimir Putin’s Russia has deteriorated to the point that it is approaching Cold War-era levels.

Washington needs better relations with China so that U.S. officials have more latitude to address the multitude of other problems. It is especially important that the United States not end up in crisis mode with Moscow and Beijing simultaneously. Circumstances now dictate that a rapprochement with an apparently chastened China be explored in the most serious manner.

Ted Galen Carpenter, a senior fellow at the Cato Institute and a contributing editor at The National Interest, is the author of nine books and more than 550 articles and policy studies on international affairs.