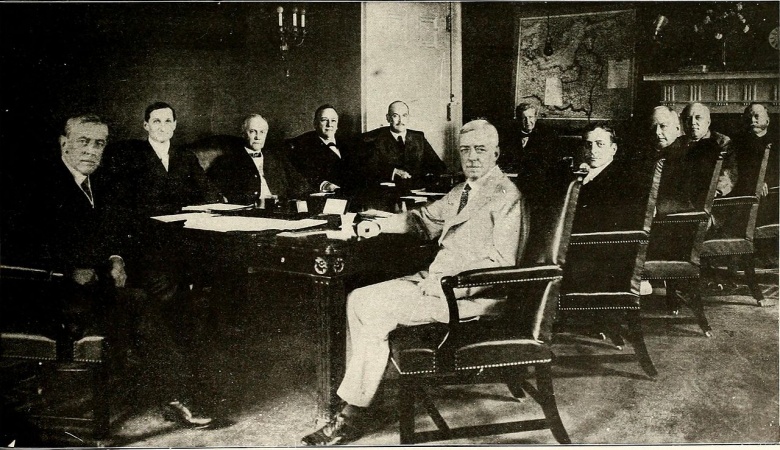

Did Woodrow Wilson Destroy the American Presidency?

Robert W. Merry’s recent post, “The Six Best U.S. Presidents of All Time,” posed some provocative questions as to how one should define “greatness in the presidency.” Unfortunately, in scholarly circles, “greatness” is too often defined as activist presidents pursuing progressive policies. Far too many scholars have a predilection for presidents such as Woodrow Wilson, Harry Truman, John F. Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson, while “caretaker” presidents, like William H. Taft, Calvin Coolidge, Dwight Eisenhower or Gerald Ford, are slighted in such polls because of their unwillingness to remake American society.

This bias toward progressive presidencies is part of Woodrow Wilson’s legacy, for the Princeton professor changed the way both practitioners and his fellow academics thought about the presidency. Both Professor Wilson and President Wilson believed that the Constitution was not fit for the complexities of twentieth-century American life. A document written at a time when the horse and buggy was the main mode of transportation was seen as an obstacle to creating an activist government capable of checking big business. Wilson held that it was the responsibility of the president to break the gridlock caused by the Constitution’s separation of powers and unleash the power of the federal government to restrain the barons of industry.

The president would break this gridlock by serving as his party’s leader, thereby bridging the separation of powers between the executive and the legislature, and would preside over an executive branch composed of experts who would regulate the economy in the interest of the common man. In addition to presiding over this regulatory state, the president would serve as an educator and visionary who would lead the nation through his oratorical skills.

The president would no longer be indebted to a political party for his selection, for presidential nominees would be chosen through primaries and the nominee would then impose his will on his party, not the other way around. Wilson’s chief executive was free to be as big a man as he wanted to be, with his power no longer anchored in the Constitution or in his party, but rooted in his personal charisma; presidential effectiveness would hinge on his personal attributes, not on any formal grant of power.

More than a century later, we continue to live under Woodrow Wilson’s regime, as scholars judge Wilson’s successors by the standards he set. Wilson upended the Founding or Constitutional understanding of the role of the president and overturned the expectations of what a president could be expected to achieve. Unfortunately, the Wilsonian conception of the presidency, adopted wholeheartedly by Democrats and eventually by Republicans, produced a massive expectations gap—a long train of heightened expectations followed by dashed hopes. The impact of Wilson’s personal presidency, or personalized presidency, can be seen in the following examples from the era of “presidential government”:

John F. Kennedy

JFK was not the choice of party leaders; his campaign was a family effort, not a party effort. Kennedy claimed that “man can be as big as he wants. No problem of human destiny is beyond human beings. Man’s reason and spirit have often solved the seemingly unsolvable—and we believe they can do it again” and that the president “must be prepared to exercise the fullest powers of his office—all that are specified and some that are not.” His vision of American omnipotence led him to proclaim that the United States would “bear any burden, pay any price” to defend liberty around the globe, including in the swamps of South Vietnam.

Lyndon B. Johnson

Johnson believed that America could win the hearts and minds of the South Vietnamese by exporting a model similar to the Tennessee Valley Authority to the Mekong Delta. His “War on Poverty” was accompanied by extravagant claims by members of his administration that poverty would be abolished in the United States by 1975. Johnson saw no boundary between himself and the office he held; when a young military officer tried to direct Johnson to his presidential helicopter, LBJ snapped, “Son, they are all my helicopters.”

Richard M. Nixon

In response to a question about alleged abuses of power during his presidency, Nixon responded, “when the President does it, that means it is not illegal.” Nixon also launched a “War on Drugs,” which is now America’s longest war, having been fought, unsuccessfully, for forty-three years.

Jimmy Carter

Carter pledged to abolish depravity in government, promising an administration that was “as good and honest, decent, truthful, and competent, and compassionate, and as filled with love, as are the American people.” Carter’s Vice President, Walter Mondale, argued that it was the proper role of government to assist “the sad.”

George W. Bush

Bush fought a “War on Terror” and sought to transform Iraq and Afghanistan.

Barack Obama

Obama noted when he clinched his party’s nomination that “this was the moment . . . when the rise of the oceans began to slow and our planet began to heal.”

These extravagant claims, and many others, produced an “expectations gap” that is fueled by inflated rhetoric, demagoguery and pandering, and would repulse the Founding Fathers (although it should be noted, in fairness, that it is also fueled by the insatiable demands of the American public). The Founding Fathers understood something many modern politicians and political scientists do not: the more you personalize the presidency and the more you inflate the presidential portfolio, the more you diminish it. It is important to note that the Founders presidency provided both a floor and a ceiling that protected but also energized the office; without this, the office is trapped in a cycle of raised expectations followed by public disappointment and cynicism.

A century of progressive disregard for the Constitution has damaged our nation’s polity, possibly beyond repair. Too much is expected of the federal government, especially the presidency. Even strong nationalists like Alexander Hamilton acknowledged limits to what the presidency should do: it should concentrate on administering the government, conduct foreign negotiations, oversee military preparations, and if need be, direct a war. The president was to avoid demagogic appeals, engage in the steady administration of the law, protect the right to property, and conduct (in partial concert with the Senate) the nation’s foreign relations. It should not attempt to democratize the world, comfort the sad, or heal the planet.

Unfortunately, the Founders’ understanding of the presidency died over a hundred years ago with the election of Woodrow Wilson (our nation’s only President with a PhD—which should serve as a warning). The prospects are remote that we can restore the Founders’ “energetic executive” and rollback some of the excesses of the Wilsonian presidency. But scholars could start by defining “great presidents” as those with an appreciation for the Constitution and a grasp of the virtue of humility.

Stephen F. Knott is a Professor of National Security Affairs at the United States Naval War College.

Image: Wikimedia Commons