A Growing Climate for Trilateral Economic Cooperation

Time for the United States, Japan and Vietnam to further increase their economic cooperation, paving the way for new trade and investment relationships.

Recent events are merging with shared strategic interests to form the basis of a strong economic partnership between the United States, Vietnam, and Japan. In July 2013, when Vietnamese president Truong Tan Sang visited Washington for the first time and signed an agreement with U.S. president Barack Obama regarding a bilateral “comprehensive partnership,” it created a strong foundation for future economic cooperation between the three nations. In 2008, Japan and Vietnam signed a bilateral economic partnership agreement (EPA)—the first such agreement for Hanoi. All three nations are also members of the World Trade Organization (WTO) and Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC), and are all aspirants to the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), which could boost their economic ties considerably.

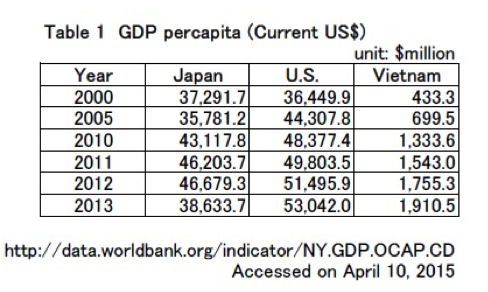

While all three countries share various common interests, they also differ in several important points of comparison. For example, all three countries have different population sizes (Japan: 127 million, United States: 325 million, and Vietnam: 93 million). All are in different stages of economic development (See table below: GDP per capita in 2013: Japan: $38,634, United States: $53,042, and Vietnam: $1,910), urbanization, and globalization, and have distinctive political histories due to different political systems. Their dissimilar geopolitical environments affect their respective priorities for the distribution of their national resources. Yet there is a growing climate for closer economic cooperation between all three nations. A look at specific opportunities in several key areas clearly demonstrates how trilateral cooperation can be enhanced. These include: (1) stronger economic ties between Japan and Vietnam and between the United States and Vietnam in the realms of trade and investment; (2) the TPP; (3) development aid to Vietnam; (4) Mekong Delta development; and (5) nuclear energy.

Vietnam: An Economic Opportunity for Japan and the United States

Vietnam’s Enhanced Trade Status

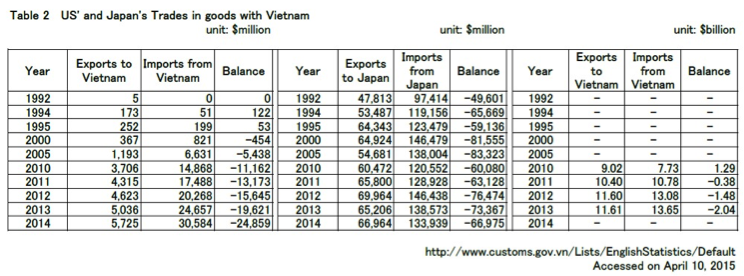

According to 2013 trade statistics, Japan ($25.2 billion) was the fourth-largest trading partner for Vietnam after China ($50.2 billion), the United States ($29.7 billion), and South Korea ($27.3 billion).[1] Vietnam held a large trade deficit with China and South Korea, whereas it had a large trade surplus with the United States ($24.7 billion for exports and $5.0 billion for imports). Japan had a fairly balanced trade relationship with Vietnam (See Table below: $11.6 billion in exports and $13.6 billion for imports).

The United States entered the Vietnamese market later than Japan did. Washington and Hanoi normalized their official relations in 1995, whereas Tokyo established diplomatic relations in 1973, twenty-two years earlier. During the Vietnam War, Japan was already a large trading partner of South Vietnam. It began to extend economic aid to unified Vietnam after 1975. However, in 1978, when Vietnam invaded Cambodia, Japan imposed economic sanctions, except for humanitarian aid, until 1991 when sanctions were lifted.

The United States imposed a trade embargo on all of Vietnam in 1975 and prohibited all bilateral trade activities. It was not until 1994 that the United States lifted its trade embargo. A bilateral trade agreement (BTA) was signed in July 2000, with trade quickly growing thereafter.

In 2006, the U.S. government granted permanent, normal trade-relations status to Vietnam, which was part of Vietnam’s accession to the WTO. In 2007, Vietnam joined the WTO as the 159th member. Vietnam and the United States concluded a trade and investment framework agreement (TIFA) that year. The two governments’ representatives met on a regular basis under the TIFA to implement Vietnam’s WTO commitments and resolve their economic- and legal-reform issues. In 2013, trade between the United States and Vietnam totaled $29.7 billion. Vietnam was the twenty-ninth-largest trading partner for the United States, but the United States was the second-largest trading partner for Vietnam after China.

Main Imports, Exports, and Points of Contention

In 2013, Japan’s main exports to Vietnam were apparel (17.5 percent) and crude oil (15.3 percent), while its main imports from Vietnam were machinery and equipment (25.5 percent), computer-related equipment and parts (15.6 percent), and iron and scrap (12.5 percent).[2] Top U.S. exports to Vietnam included agricultural products (23.2 percent), food manufactures (16.3 percent), and computer and electronic products (14.3 percent), whereas top U.S. imports from Vietnam were apparel and household goods—cotton (17 percent), apparel and other textiles (16 percent), and furniture, household items, and baskets (11 percent).[3]

Both Tokyo and Washington are concerned over the large role that state-owned enterprises still play in Vietnam over the industrial sector, such as mining and energy, and also the formal and informal control by the Vietnamese government over prices in the market. America treats Vietnam as a “nonmarket economy” under its trade law, while Hanoi wants this designation to be changed to “market economy.” Yet on the whole, the Vietnamese economy is growing quickly, providing benefits to both itself and its two partners.

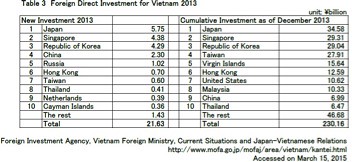

Expanding Investment

Since 2006, foreign direct investment in Vietnam has been growing rapidly. The sum of investment for 2007 was $8 billion, increasing to $11.5 billion the following year. In 2013, Japan was the top investor in Vietnam. Tokyo’s investment of $5.75 billion is one quarter of the total amount of direct foreign investment ($21.63 billion) that Vietnam approved that year (see table on next page for additional information).[4] The accumulated investment ($230.16 billion) that year also placed Japan ($34.58 billion or 15.0 percent) on top. This was the result of important bilateral agreements, including the Japan-Vietnam Joint Initiative (2003), the Japan-Vietnam Investment Agreement (2004), and the bilateral EPA (2009). The Joint Initiative for investment was to formulate “an action plan” for the government and private sectors to improve Vietnam’s investment environment through five phases. The agreement was to promote the liberalization of investment and to protect investors’ rights.

In 2013, the United States was not among the top ten investors in Vietnam; however, it ranked as the seventh-largest investing country, in terms of accumulated investment, with $10.62 billion.

Vietnamese firms have begun to take interest in investing in the United States. Vietnamese furniture companies have expressed interest in investing $5 million to set up a manufacturing facility for storage furniture and kitchen cabinets.

The Vietnamese government plans to industrialize its economy by 2020, with its electronics, agricultural-machinery, agricultural and marine-resources-processing, shipbuilding, environmental-improvement and energy-saving, and automobile and parts fields functioning as strategic industries. Prolonged labor-intensive industries and the stagnant transition to industrialization may induce foreign firms to move to other countries where labor wages are lower, as Vietnam will have to raise labor wages when supply chains enter from ASEAN countries and China.

The Trans-Pacific Partnership: Tough but Hopeful Talks

Background

The TPP was originally signed by four nations in May 2006: Brunei, Chile, New Zealand, and Singapore. Between January 2010 and July 2013, eight other nations expressed interest in signing on, including Japan, the United States, and Vietnam. While these eight countries have been negotiating to finalize an agreement, the two biggest participants are clearly Japan and the United States, whose GDPs together equal 81 percent of the total twelve possible TPP nations’ combined GDP and 29 percent of the global GDP.

As of early May 2015, negotiations between Japan and the United States have been pressing ahead. The prevailing view is that the negotiations should be settled before the end of 2015, so that the TPP will not be entangled in the upcoming U.S. presidential campaign. Yet it is difficult to see the end of negotiations in the near future, although the two sides acknowledged in late April that they are much closer to a final agreement.

Economic Benefits of the TPP

Is an enhanced partnership between Japan, the United States, and Vietnam likely to come about under the framework of the TPP? At the very least, if the TPP is adopted, the impact on all three nations could be wide reaching.

One research study estimated in 2012 that if the TPP became a reality, the United States could expect real income benefits of $77.5 billion per year and U.S. exports could increase by 124.2 billion by 2025.[5] Similarly, Japan’s GDP could increase by $119.5 billion, and Vietnam’s by $46.1 billion. The same research noted that Japan’s exports would increase by $175.7 billion, and Vietnam’s by $89.1 billion.

Vietnam will probably lag behind other prospective members of the TPP in terms of opening its own market, since Hanoi’s average tariff rate is the highest (10.9 percent) among the negotiating countries.[6] Nonetheless, it is speculated that if the TPP does go into effect, Vietnam will be able to compete favorably with China in exporting textiles to the U.S. market, since the United States conditions the import of Vietnamese apparel, made only from yarns of Vietnamese origin. In fact, Vietnam may be among those TPP members that benefit the most.

The TPP and the U.S. “Rebalance” to Asia

Beyond the economic realm, the TPP is an important strategic part of the U.S. “rebalance” policy—seeking to restrain China’s economic power. Japan shares with the United States the goal of promoting a regional free market along with liberal democratic principles through TPP. Yet, as of early May 2015, the two Pacific nations cannot agree on areas where important concerns remain, including automobiles and agricultural products.