Pariahs in Tehran

Mini Teaser: We shouldn't believe all we hear about the success of Obama's Iran strategy. The world needs to put a stranglehold on Tehran.

THE MOST interesting thing about the Obama administration’s Iran policy is that it is working, but it probably isn’t going to work.

THE MOST interesting thing about the Obama administration’s Iran policy is that it is working, but it probably isn’t going to work.

The United States has achieved some truly remarkable feats in pursuit of the White House’s Iran policy over the course of the past twelve months, achievements many critics from left, right and center all thought impossible. With perseverance and perspicacity, and some help from the stupidity of the Islamic Republic’s leadership, Washington has secured widespread backing in Europe, East Asia and the Middle East for imposing various new sanctions on the country.

Of greatest importance, in June 2010 the administration secured the passage of a new UN Security Council resolution (number 1929) that imposed a fourth round of sanctions on Tehran for its failure to comply with its obligations to the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) and its failure to cease its nuclear-enrichment activities. In concert with France, Britain and Germany (and some quiet help from Israel, Saudi Arabia and the UAE), the United States convinced both Russia and China to agree to the new resolution as well. Resolution 1929 bans arms sales to Tehran, something most thought unthinkable given the Russian and Chinese ardor to continue profiting from that market. It also included language that enabled member states to impose harsh new financial controls and limits on investment in the Iranian energy sector.

The Russians have even gone so far as to privately convince their own oil giant, Lukoil, to stop selling gasoline to Iran. The Europeans have likewise pushed Shell and a variety of other major firms on the Continent to reduce their purchases of Iranian oil, and major European banks and businesses are shutting down their operations in the Islamic Republic. The new sanctions, both those contained in the resolution itself and those enacted by member states (particularly the EU, Japan and South Korea) in conformity with the provisions of the resolution, go far beyond what most believed possible. They truly are harsh measures, something U.S. officials had hoped for and threatened, but in private had doubted would be diplomatically feasible. And they have gotten Tehran’s attention, with no less a figure than former-President Ayatollah Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani warning his countrymen that the sanctions are no joke and that the country’s situation is dire.

Indeed, since the passage of the UNSCR, the Iranian regime has been broadcasting on all frequencies, overt and covert, that it is ready to talk seriously with Washington about its nuclear program. For this reason, it seems likely that the United States, along with Britain, France, Russia, China and Germany (the P5+1), will sit down with Iranian representatives before the end of this year for formal negotiations. It is also likely that Iran will offer to discuss reprocessing its low-enriched uranium (LEU) to refuel the Tehran Research Reactor, something it already agreed to in a deal brokered by Brazil and Turkey in an eleventh-hour effort to stave off the UN sanctions vote. The Iranians are reportedly hinting that such an agreement with the P5+1 could lead to further deal making over its nuclear program more generally.

All of this constitutes a tremendous turnaround from Bush 43. It’s not surprising that the White House would want to believe that its successes will pay off, compelling Tehran to bow to international pressure and agree to a deal on its nuclear program in toto.

But just because the administration’s critics have been wrong, does not mean that they will be wrong.

THE PROBLEM with Washington’s current approach is that it is intended to put intense-enough pressure on Tehran that the government will negotiate a halt (or even a rollback) of its current nuclear program. It is a reasonable position—one I proposed back in 2004 and staunchly supported up until Iran’s disputed presidential election on June 12, 2009. But it is no longer enough.

June 12, 2009, and the weeks that followed were a watershed for the Islamic Republic. The regime confronted its most dangerous internal threat ever as millions of Iranians took to the streets and to their rooftops to protest what they believed was a stolen election. For the first time, they demanded the resignation of Iranian Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. In effect, they demanded an end to the Islamic Republic itself.

At that moment, the more moderate voices within the Iranian establishment counseled making concessions to the opposition. These were the leaders of the Iranian reform movement and, not coincidentally, the same people who had shown a willingness to negotiate with the West in the hope of alleviating Iran’s crippling economic and diplomatic problems—from unemployment to declining oil revenues to rampant corruption. However, Tehran’s hard-liners, particularly the leadership of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, insisted on cracking down on the opposition instead. So too did the supreme leader, who apparently believes that the shah fell because he was weak, having compromised with the revolutionaries (including himself). The ayatollah sees those very concessions as the beginning of the end of the shah’s rule. Neither Khamenei nor the Revolutionary Guard, nor any of Iran’s other hard-line leadership, plans to be ousted the way that the shah was, and they have made clear that they will employ whatever levels of violence are necessary to retain power.

In the weeks and months that followed, the regime embarked on a massive, systematic and brutal, but also highly sophisticated, crackdown that for all intents and purposes crushed the street protests of the opposition Green movement. Simultaneously, the regime’s hard-liners effectively “purged” the government’s more moderate elements. Some were imprisoned; most were simply left in place but deprived of power—which in Iran’s Byzantine system of personal politics derives largely from informal influence ultimately bestowed by the supreme leader himself.

Thus, today, Tehran’s hard-liners dominate Iranian decision making in ways that they have not since the early 1980s. Of course, there are still fissures even within these innermost circles—it is Iran after all. However, the problem for the Obama administration is that Iran’s hard-liners have shown absolute consensus in consistently maintaining that Iran needs, and is entitled to, its nuclear program. Some have gone so far as to question the utility of Iran remaining part of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT); some have openly supported the acquisition of nuclear weapons. Ayatollah Muhammad Taqi Mesbah-Yazdi, a member of the Assembly of Experts and an important adviser to President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, wrote that Tehran “must” produce nuclear weapons even if Iran’s “enemies” don’t like it.

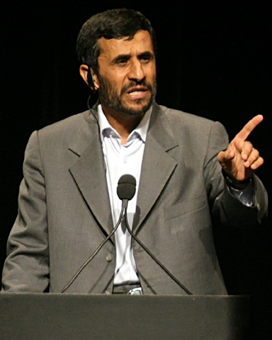

What’s more, the hard-liners overwhelmingly neither want nor care about having a better relationship with the United States. President Ahmadinejad is the exception that proves the rule: alone among the hard-liners, he has called for negotiations with the Americans, but only to demonstrate that Iran is so powerful and important that it must be seen as an equal by the United States. Ahmadinejad has been fiercely opposed by the rest of the Islamic Republic’s hard-line establishment, including (as best we can tell) by Khamenei himself.

Ultimately, Tehran’s hard-liners insist that Iran is strong enough to withstand and outlast any sanctions that might be imposed upon it, and they are certain that everyone else will realize that the world needs Iran more than Iran needs the rest of the world. Certainly, they might ultimately change their minds. Muammar el-Qaddafi once believed much the same about Libya. He eventually figured out that he was mistaken, and he was forced to give up his own nuclear program and make amends with the United States and the international community. But even that took ten years, and Iran is a lot bigger and a lot richer than Libya—a point that Tehran’s hard-liners regularly recite.

As Iran scholar Ray Takeyh nicely summarized the problem:

The essence of Washington’s approach is that confronted with a choice of debilitating isolation or rejoining the community of nations, Iran will eventually make the “right” decision. The Islamic Republic, however, is too wedded to its ideological verities and too subsumed by its rivalries to engage in such judicious determinations.

So even if the Obama administration is able to build a sanctions regime as harsh as that imposed on Libya, we should not assume that it is going to succeed—be it in months or in years. Given Iran’s size, oil wealth, internal paralysis, and ideological and nationalist stubbornness, history suggests it is going to take a long time to work—if it ever will.

OF COURSE, the catch is that unless and until the sanctions succeed, Iran’s nuclear program will keep plugging along. Within a few years, Iran is likely to have the capability to produce nuclear weapons and, should the regime so desire, could deploy a full-blown arsenal soon after.

This is why a growing number of Americans want to give up on pressure and persuasion altogether and instead just bomb Iran’s nuclear program. It’s easy to empathize with the fear and frustration that drives smart, patriotic people to embrace air strikes as a means of eradicating the potential threat from Iran’s nuclear program. It is not an option I would rule out unequivocally, but it is an option with a great many flaws.

Image: Pullquote: The United States needs to make Iran a true pariah state, and one squeezed enough from both outside and inside that it eventually recognizes it would be better to make some concessions than continue under the strain.Essay Types: Essay

Pullquote: The United States needs to make Iran a true pariah state, and one squeezed enough from both outside and inside that it eventually recognizes it would be better to make some concessions than continue under the strain.Essay Types: Essay