Arizona – The Last Navy Super Dreadnought Battleship

It has been common practice in recent years for U.S. Navy sailors who served on the battleship USS Arizona (BB-39) to have their ashes scattered over the wreck site – a way for them to be reunited with those crew members who were lost when the ship was sunk on December 7, 1941. More than thirty sailors who survived the attack had chosen the site as their final resting place.

The warship had been moored inboard of the repair ship Vestal (AR-4) on that fateful Sunday morning in December. She was struck by several bombs, which caused damage to her aft and midship sections. The massive explosions that followed have never been fully explained – and many theories abound – but it caused a fire that burned furiously for more than two days.

A total of 1,177 officers and crewmen were killed, including Rear Admiral Isaac C. Kidd, Commander Battleship Division One, and the ship’s Commanding Officer, Captain Franklin Van Valkenburgh.

The destruction of USS Arizona was a devastating blow for the United States given the tremendous loss of life, and no doubt the Japanese saw her destruction as a victory; the truth is that the warship was rather antiquated at the time.

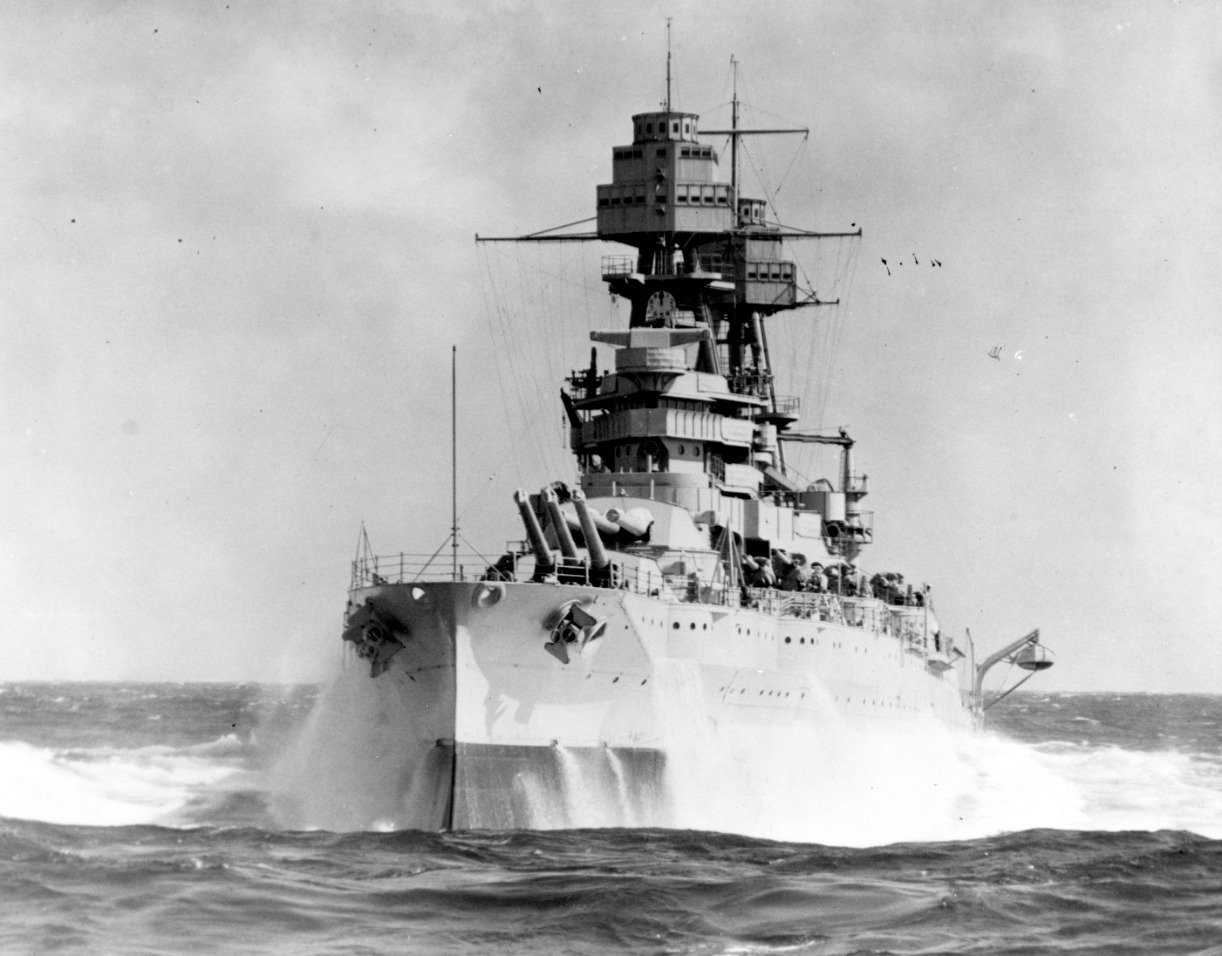

She was, however, the second and last of Pennsylvania-class of “super-dreadnoughts” built for the United States Navy in the early 20th century.

Here is a short history of the iconic battleship:

USS Arizona: The Navy’s Super Dreadnought

Construction of Arizona – then known simply as Battleship 39 – began in March 1914 at the Brooklyn Navy Yard, which ran twenty-four hours per day and at full capacity employed 70,000 workers. It was originally assumed the warship would be named North Carolina in honor of the home state of Josephus Daniels, the Navy secretary.

Commissioned in 1916, the battleship remained stateside during the First World War but was one of several warships that escorted President Woodrow Wilson to the Paris Peace Conference in the summer of 1919.

The Pennsylvania-class was meant to greatly improve upon the Nevada-class – and the vessels were the largest U.S. Navy battleships built to that point. They were 608 feet long and had a beam of 97 feet at the waterline. Each carried twelve 14-inch/45 caliber guns in triple turrets, as well as twenty-two 5-inch/51 caliber guns. However, the twelve water-tube boilers and four shafts gave the warships a top speed of just twenty-one knots. They were essentially slow, lumbering beasts.

BB-39 underwent a comprehensive modernization effort from 1929-31, much of which can actually be seen in the 1934 film Here Comes the Navy, which starred James Cagney. In the late 1930s, she was largely used for training exercises and had been sent with the rest of the Pacific Fleet from California to Pearl Harbor as a deterrent to Japanese imperialism.

Unlike many of the other U.S. Navy warships that were sunk or damaged during the attack on Pearl Harbor, Arizona did not return to duty. It was determined she could not be salvaged, and instead, her surviving superstructure was taken down in 1942 while her main armament was salvaged and used for coastal defense batteries. One of those batteries fired for the first and only time on V-J Day in August 1945. Additionally, guns from Turret II were salvaged and later installed on the USS Nevada (BB-36), which had also been damaged on the December 7 attacks. The guns were fired on Japanese positions in Okinawa and Iwo Jima.

Today, Arizona is unique in that the wreck site is now under the control of the National Park Service, but the warship retains the right, in perpetuity, to fly the United States Flag. In 1949, the Pacific War Memorial Commission was established to create a permanent tribute to those who lost their lives, but it wasn’t until a decade later that President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed the legislation to create a national memorial. Funds to build it came from both the public sector as well as private donors.

The memorial received more than ten percent – $50,000 – from a benefit concert in March 1961 featuring Elvis Presley, who had recently finished his service with the U.S. Army.

Peter Suciu is a Michigan-based writer who has contributed to more than four dozen magazines, newspapers, and websites.