Coronavirus Could Force Universal Healthcare to Be a 2020 Election Issue

A lot can change in a few months.

Richard Titmuss, a British pioneer of social policy, published an influential book called The Gift Relationship in 1970. It reflects on the altruism that underpins voluntary blood-donation systems like those of the UK and most other European nations.

He demonstrated that such systems were superior to those based on market principles, such as the US, where donors were paid for blood by private enterprises. Compared to the UK, this resulted in fewer donations and poorer quality blood. The Gift Relationship became a bestseller in the US, and it led the nation to move away from market-based blood collection.

Around the same time, health economists were reflecting on the more general question of healthcare as a commodity. In parallel with Titmuss, they landed on the notion of the caring externality. This is the idea that markets do not serve us well when the commodity in question is one where we care about, and thus value, the access of others.

The best way of extracting money from those who care and transferring it to those in need is the tax system. Combined with the inequities and high administration costs of private insurance, it explains why the NHS has endured in the UK – along with similar systems throughout advanced economies. It also explains why many other countries have the same goal.

American exceptionalism

The US is the exception among richer nations. It has not done with healthcare what it did for blood donation, despite extending coverage to some extent over the years. Health spending per capita is way above rival economies, and yet almost one in ten Americans have no healthcare coverage in this system.

Indeed, “system” is a misnomer in US healthcare. It comprises several systems including not only private insurance but the Veterans Administration, Medicare and Medicaid, much of which is not integrated with either primary care or public health.

Attempts to move to publicly funded universal coverage have continually failed or been compromised. Most recently, President Donald Trump promised to “immediately” introduce health insurance for everybody at much lower prices than Obamacare, but this remains in the long grass nearly four years after he was elected.

Now American healthcare is under the microscope like never before. Bernie Sanders’ presidential campaign set the scene by making universal health coverage a cornerstone policy. The Vermont Senator’s “Medicare for All” would have virtually eliminated private insurance in favour of full publicly funded coverage – with a few exceptions in relation to dentistry, certain surgeries and so forth.

Joe Biden, Democratic nominee apparent, is not backing such a transformation, but he has gone as far as committing to a “public option”. This would enable anyone, regardless of income, to buy into a pre-existing public scheme that would probably end up much cheaper than private insurance.

Enter the coronavirus

How is the global pandemic affecting this debate? The key is how the US public views the efforts of more coordinated publicly funded systems in dealing with the virus. There are of course caveats about demographics, different stages of disease progression, and what measures are possible in different cultures. But many nations, including the ultra-interventionist Chinese, appear to have been better at marshalling testing, isolation and treatment – as well as behavioural initiatives to fight the virus.

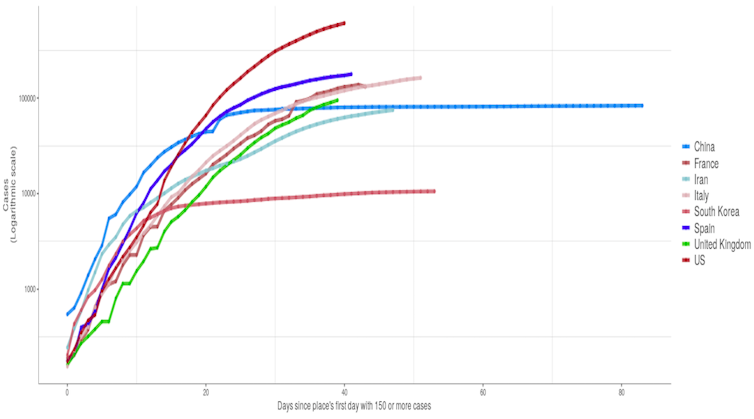

In terms of deaths, the US is already accelerating past the likes of China and South Korea – click on the graph below to make it bigger. China’s death rate, in mid-blue, has completely flattened out. The other flattened line is South Korea, whose fast-response regime of test-and-isolate has kept deaths relatively low so far.

Cases since first day with 150+ cumulative infections

The US public might well be asking if their own system somehow lacks the ability to organise in such similar ways – particularly when poor people and black people are being hit disproportionately hard by the virus. This is inevitably being pointed out by supporters of Medicare for All, which includes the American College of Physicians.

But voters appear to be moving in the same direction. Two in five Americans say that the pandemic had made them more likely to support universal healthcare, including one in four Republicans. Another survey showed twice as many voters in favour of Medicare for All than those against it.

Biden said several weeks ago that the pandemic had not changed his mind on Sanders’s scheme, pointing out that Italy has such a single-payer system and has still been hit very hard. New York’s Democrat governor, Andrew Cuomo, has also refused to back such reforms, but he has certainly been loudly highlighting the inadequacies of the system.

In light of this and the unfolding public health disaster in the US, it seems like the sort of climate in which great shifts might be possible. Perhaps it is time for the American public not only to adopt the mindset of The Gift Relationship and the caring externality, but actually to ensure they are enacted into public policy.

For his part, Trump recently said he wants to extend Medicare/Medicaid to the 30 million Americans who don’t have it. Such an acutely political operator will certainly be aware that having the wrong policy on American healthcare going into the presidential election could bring about almost anyone’s downfall in a year like 2020. With a long and difficult period ahead for the US, who can say what will be on the table by the autumn.

![]()

Cam Donaldson, Yunus Chair and Pro Vice Chancellor Research, Glasgow Caledonian University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Image: Reuters