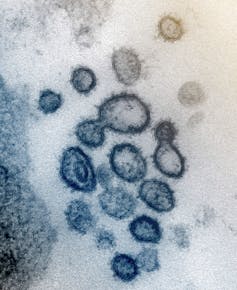

A Coronavirus Vaccine Must Be Affordable and Accessible to the Public

Globally, billions of dollars in public funds have been committed to a COVID-19 vaccine development. It’s crucial that the resulting vaccine be accessible to all.

The race is on to develop a vaccine to protect against COVID-19. Germany, the United States, the European Union and others have collectively committed more than a billion dollars.

On March 11, Canada announced it would provide $275 million toward the research and development of some of the world’s most promising candidate vaccines, diagnostics and therapeutics, among other public health and clinical research.

Public funds are the backbone of the underlying science that’s needed to develop the medical tools that we need and use. But today there is little indication — and no requirement — that the billions of public dollars being spent will result in a vaccine or treatment for COVID-19 that is affordable.

Instead, governments appear poised to let the private market sort out the details of who gets access and at what price. Their logic is that public funding should be used to support early stage discovery, but that the research should ultimately transferred to private companies in order to be fully developed and priced based on what the market can bear. This logic, whether for COVID-19 or for any other disease, is flawed.

For its $275 million investment, Canada has yet to announce what safeguards it will enact to ensure that the vaccines, diagnostics and therapeutics it develops are affordable and accessible to the people and health systems that need them. Given the massive public contributions being made, governments must ensure that the return on these investments comes in the form of lifesaving health services that are free for patients and affordable for health systems — not in the form of high profits for private companies. This is not only the ethical thing to do, it’s also what makes sense as a matter of global public health policy.

Lessons from the Ebola vaccine

Canada has recent experience in developing a vaccine that the world needed. The rVSV-ZEBOV vaccine for Ebola was developped by researchers working at the National Microbiology Laboratory in Winnipeg in the early 2000s. Yet the vaccine was only approved for use by the European Medicines Agency and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in the fall of 2019, nearly 20 years after it was first developed and many years after the completion of the clinical trial showing it was effective.

Why the delay? For a long time, there was simply no financial interest from the private sector in moving it forward — Ebola outbreaks occur in countries that can’t afford the prices that make vaccine development lucrative for pharmaceutical companies.

As the Canadian government shopped around for a private sector partner to develop and commercialize the vaccine, there was little interest. One company with no previous experience bringing a vaccine to market acquired the rights in 2010 for $205,000 and has since sub-licensed the vaccine to Merck for US$50 million after having apparently done little to advance the development of the vaccine despite being contractually obligated to do so.

As a colleague put it recently in testimony to Parliament’s Standing Committee on Health, there is no law of physics that says that the private pharmaceutical industry has to do research and development of lifesaving drugs and vaccines. In fact, the private sector has shown itself to be remarkably out-of-step with many global public health priorities, walking away from research and development of things we all need — like new antibiotics. They have, however, become adept at demanding high prices under the threat of delaying the launch of new medicines if these pricing demands aren’t met.

Public funds don’t guarantee accessible drugs

It is essential that we learn the lessons from the Ebola vaccine and many other discoveries that have been supported by public funds and get it right, not only with COVID-19 but with our whole approach to publicly funded health innovation. Governments around the world play an integral role in supporting the science that leads to discovering lifesaving technologies.

In Canada alone, researchers in publicly funded labs have discovered an Ebola vaccine, insulin, the cardiac pacemaker, a vaccine for haemophilus influenzae and many others.

While Canada and other governments have supported this important work by directing funding towards universities and research institutes, these funding models generally fail to capture the process from discovery through to use, and instead rely on universities or the researchers themselves to figure out how to get their game-changing discoveries to patients.

Historically, they’ve done this by commercializing their discoveries via the private sector, giving one company exclusive rights to do the subsequent development of the technologies and then to control the sale and price of them when they become a product — with no safeguards or assurances to ensure that patients would have affordable access once the drug or vaccine hits the market.

This no-strings-attached approach to science is foolhardy in an era of patients dying because health systems can’t afford drugs that now routinely cost hundreds of thousands of dollars for some conditions, and where companies are already gearing up to massively profit off of COVID-19 vaccines and therapeutics.

As these new medical tools are developed, licensed and become commercially available, there is a real risk that, given the way the biomedical innovation system works today, they may be rendered inaccessible to those who need them. This should be unacceptable to Canadians, considering the significant public investment that’s been made.

Making access a priority

Canada can get this right. We have world-class scientists who by all accounts have promising candidate vaccines and therapeutics for COVID-19 in the works. We should support their work with public funds through Canada’s research granting councils and other mechanisms.

But we should not blindly accept that the only way these productive, world-class scientists can get their vaccines and therapeutics to patients is by selling them to pharmaceutical companies without negotiating access for patients and health systems upfront. We need safeguards that ensure that if the public paid for it, Canadians and everyone else around the world who needs it will be able to access it quickly and affordably, at a fair price. Public funds should deliver medicines and vaccines that are affordable for the public.

Read more: Coronavirus weekly: expert analysis from The Conversation global network

Canada may not even have to depend on commercial partners to bring medical innovation from the lab bench to the patient’s bedside. The experience of the Ebola vaccine’s development shows that public sector researchers did much of the heavy lifting in the development and even manufacturing of early batches of the vaccine. We have experts in clinical trials in our hospitals, universities and vaccine research groups who are more than capable of doing the necessary clinical trials to develop and deliver new health technologies quickly and affordably.

We can do health research and development differently, in a way that prioritizes access and affordability for patients and ends the profiteering off sick people in times of crisis. Let’s get to work.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Jason Nickerson is a Humanitarian Affairs Advisor at L’Université d’Ottawa/University of Ottawa.

Image: Reuters