The Hand Cannon That Failed: The Army Had High Hopes for the T-148 Grenade Launcher

In 1953, U.S. Army Lt. Col. Roy Rayle took up his new post at Springfield Armory. Best known for his work on the M-14 rifle and M-60 machine gun, he spent his time at the government arsenal taking part in several different projects — including the development of the T-148 grenade launcher.

The Army hoped the 40-millimeter weapon and its three-round magazine would make for a deadly hand-cannon. In theory, it would give soldiers even more firepower compared to the single-shot version Springfield engineers were cooking up at the same time.

“The Infantry Board at Fort Benning had specified a three-shot grenade launcher, and that was our main effort,” Rayle recalled in Random Shots: Episodes in the Life of a Weapons Developer. “By 1955 … I began to worry about the awkwardness and poor accuracy of the three-shot launcher.”

The Army weaponeer was right to be concerned. Over the next decade and a half, American troops in Vietnam found that the launcher was simply too bulky and fragile for combat.

The T-148 developed from a larger project to give troops the ability to launch explosives, and do so accurately, farther than they could chuck hand grenades. Experiences from World War II and the Korean War undoubtedly informed the Army’s goals.

“Men in battle cannot think as grenadiers unless they have been specifically schooled as grenadiers,” U.S. Army historian Brig. Gen. S.L.A. Marshall complained in a detailed 1951 analysis of weapons used on the Korean Peninsula — his emphasis. “For almost 30 years now, the Army has discounted the value of systematic grenade training.”

Marshall found that commanders gave extra grenades to soldiers they saw as having the strongest arms, regardless of how well they could actually toss the small bombs. Officers were dismissive of rifle grenade launchers — a device attached to the front of a rifle that lobs grenades at longer ranges — and individuals who had skill with them.

By the end of 1951, the Army had started work on an all-new grenade launcher. The weapon would fire a new, self-contained projectile that looked like an oversize bullet.

This 40-millimeter cartridge was something of a revolution. The projectiles only armed after they flew, spinning, away from the barrel — making them relatively safe to carry and shoot.

If a grenadier accidentally missed the mark and hit something close by, the grenade likely wouldn’t explode. Dropping a live hand grenade was not nearly as forgiving.

On top of that, the new rounds could easily fly more than 400 yards. This was well beyond the distance most people could accurately throw a baseball, let alone a hand grenade and was approaching the minimum effective range of a small mortar.

However, unlike a mortar, recoilless rifle or heavy machine gun, the prospective launcher promised to have such little recoil that it could still be relatively light and compact. The grenade rounds were so tame that Rayle and his companions experimented with a pistol-type launcher similar to an emergency flare gun, but that weapon turned out to be too inaccurate.

Enter the T-148.

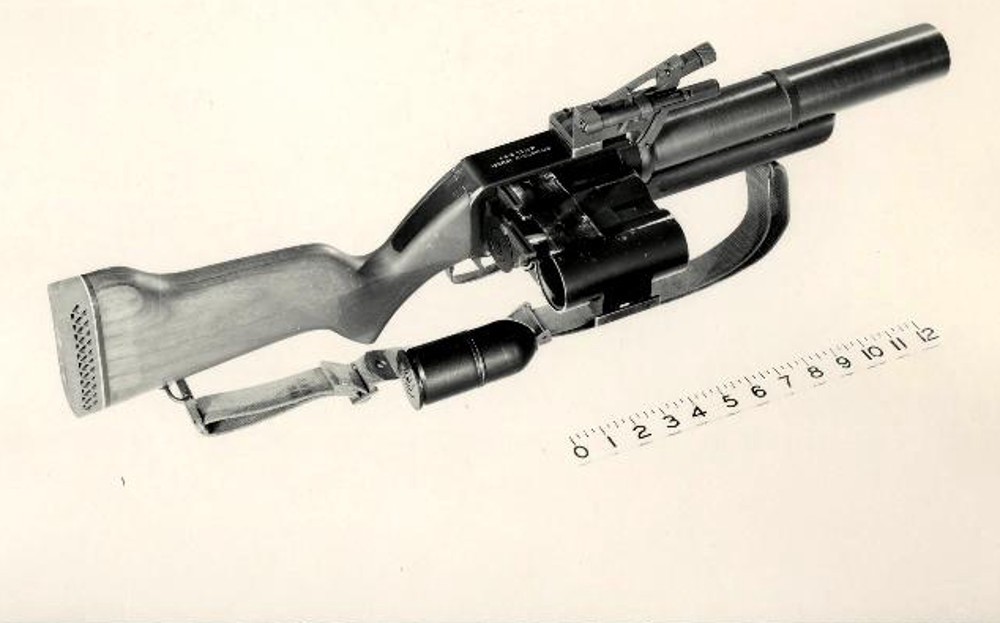

With a weight of less than nine pounds and a length of just under 30 inches, according to a 1960 Army training manual, the launcher was effectively the same size as the M-1 and M-14 infantry rifles. Looking something like an over-sized shotgun, troops fed the gun with rectangular three-round magazines.

Unlike more common gun designs, a soldier would slot the ammunition into the right side of the T-148. The bulky magazine would then slide to the left as the shooter squeezed off shots.

This arrangement is commonly known as a “harmonica gun,” since the rounds slide akin to how the musical instrument moves in a player’s mouth. But the magazine would never fall out the other side, even after the shooter ran out of ammunition.

To reload, the solider could either remove the cluster of empty chambers or keep it attached to the gun and add three fresh rounds individually. Separately, the Army designed special belts, bandoliers and vests to carry spare 40-millimeter grenades.

But despite its potential, the T-148 was hardly perfect. As Rayle discovered, it was awkward and bulky.

Each 40-millimeter round weighed eight ounces. This was enough for the shooter to feel the weight of the whole gun shift as they fired one grenade after another — easily throwing off a person’s aim.

The ammunition feed was fragile to begin with and had large, open spaces for dirt and other things to get jammed in. Springfield Armory eventually developed three groups of prototypes, with the final T-148E2 featuring stronger materials throughout.

In addition, Rayle and his fellow weapon designers had started work on a backup launcher. This weapon — dubbed the XM-79 — was a crude, but simple single-shot grenade gun that worked like a break-action hunting shotgun.

In spite of the problems, Army officials remained most interested in the T-148 and other multi-shot designs. However, they had to concede that the simpler alternative was working out much better.

As American troops — especially elite Special Forces soldiers — began heading to South Vietnam in greater numbers, many arrived carrying the final production version of the M-79. A small number of T-148s made it onto the Southeast Asian battlefield, too.

There, it seems, Army troops confirmed Rayle’s negative experiences with the gun. Though some soldiers continued to use the T-148s well into the 1960s, no one was apparently begging for more of them. The U.S. Navy SEALs reportedly obtained one and quickly decided it was more trouble than it was worth.

Even after troops got launchers they could strap underneath their rifles, the M-79 soldiered on. Regular American troops and commandos were still using the launchers in combat in Afghanistan and Iraq in the early 2000s.

The T-148 quickly faded from view. In Random Shots, Rayle himself never refers to it as anything other than “the three-shot launcher.”

This article by Joseph Trevithick originally appeared at War is Boring in 2017.

Image: U.S. Army