How the Royal Navy Used Radar to Sink the Deadly Nazi Battleship Scharnhorst

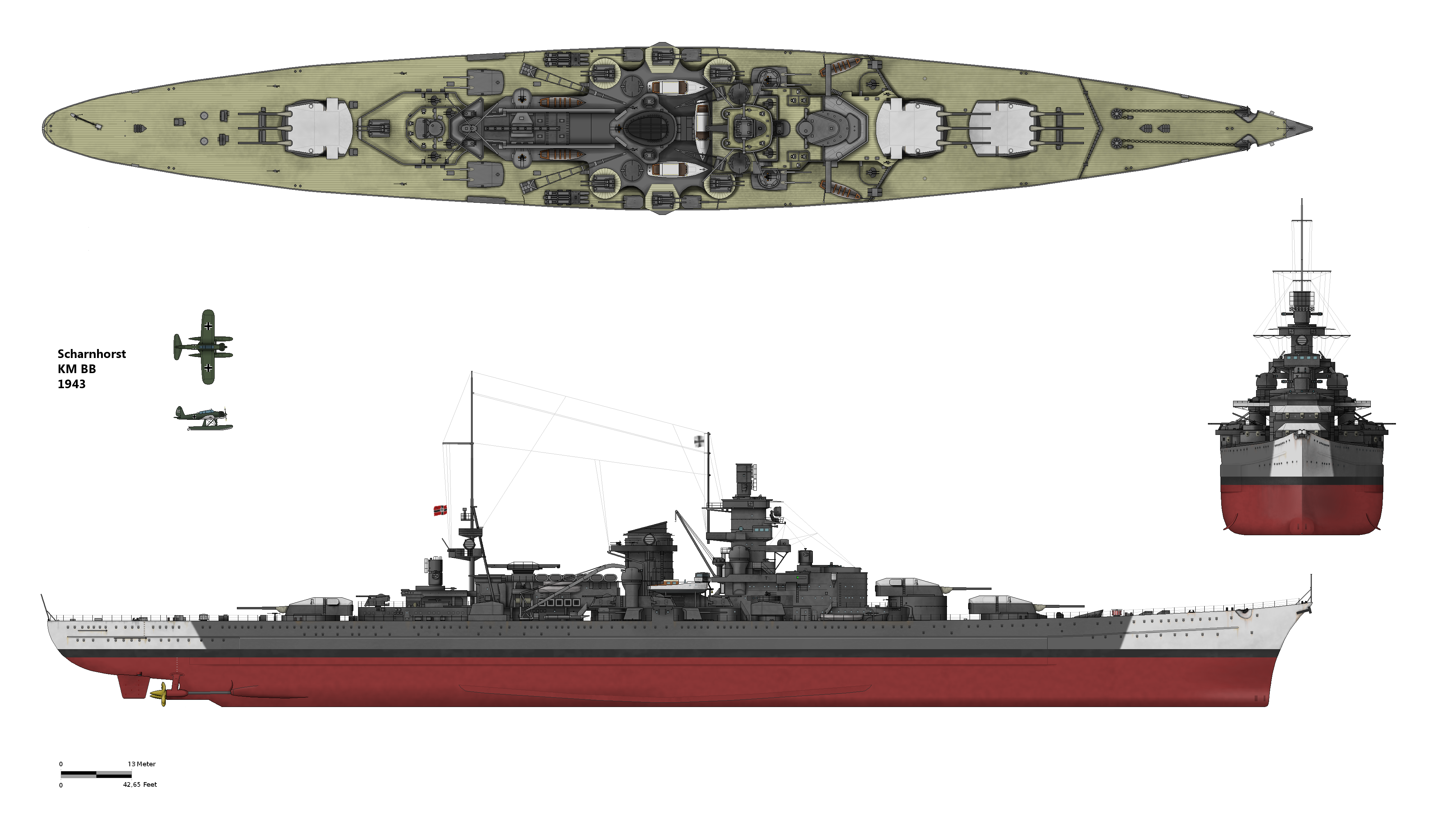

The Scharnhorst was far from the most heavily armed battleship deployed by the Kriegsmarine—but she arguably was its most successful. She and sistership Gneisenau were laid down in 1935 with nine 283-millimeter guns with a range of twenty-five miles—significantly smaller than those on British battleships so as not to spook London over German rearmament.

Nonetheless, Scharnhorst measured 234 meters, which is longer than two football fields, and displaced a massive forty-two thousand tons fully loaded with fuel, ammunition and a wartime-crew of nearly two thousand men. The ship’s three Swiss-built steam turbines allowed her to attain flank speeds of thirty-one knots or higher—fast enough to outrun most warships. Indeed, Scharnhorst was a battlecruiser designed to chase down and overmatch smaller vessels rather than duel enemy battleships.

The Scharnhorst’s guns were mounted in 750-ton triple-gun turrets named Anton and Bruno in the bow, and Caesar on the stern. Twelve quick-firing 150-millimeter guns provided additional firepower. The Scharnhorst’s two Seetakt radars, one forward and one rearward-facing, had a surface-search range of around ten miles and were primarily used for gun-laying. Three Arado 196 seaplanes served as the battlecruiser’s long-range “eyes.”

For air defense, the Scharnhorst additionally mounted seven twin 105-millimeter flak turrets that could spit air-bursting shells up to forty-thousand-feet high, and dozens of smaller thirty-seven-millimeter and twenty-millimeter auto-cannons for close defense. She was well-protected from long-range hits by up to fourteen inches of Krupp cemented steel girding her turrets, bridge and hull. However, her two-inch deck armor was vulnerable.

For all her speed, the Scharnhorst was not highly maneuverable and frequently returned to port damaged by rough seas. In sea trials after commissioning in January 1939, the Scharnhorst’s bow took on so much water she was promptly refitted with a flared “clipper-style” bow.

Despite these flaws, the Scharnhorst proved far more than the Kriegsmarine’s other capital ships. On her maiden war-cruise in November 1939, she sank the auxiliary cruiser HMS Rawalpindi. Then in June 1940, the battlecruiser ambushed the aircraft carrier HMS Glorious, sinking her and two escorting destroyers, though Scharnhorst sustained a torpedo hit in battle.

Like an outlaw continually outwitting justice, the Scharnhorst was a notoriously “lucky” battleship, weathering numerous attacks by British bombers. In 1941, she managed to slip into the Atlantic and sink ten merchant ships, then evaded retribution under cover of sea squall to make port at Brest, France where she was outfitted with six torpedo tubes.

Heavily damaged in a July 1941 air-raid, Scharnhorst joined other German capital ships five months later in the notorious “Channel Dash” that was staged under the nose of Britain’s coastal defense, though she struck two mines in the process.

However, by 1943, German capital ships had fallen out of favor with Hitler after the Battle of the Barents Sea, a botched attack on an Arctic convoy carrying Allied aid for the Soviet Union. The Fuhrer had to be talked back from scrapping all his capital ships.

As the Wehrmacht’s woes in Russia mounted, in December 1943 Adm. Karl Donitz decided to again attempt a surface sortie targeting the Arctic convoys as they skirted past German-occupied Norway—and tapped Scharnhorst for the job.

However, not only were the British listening in to Donitz’s radio messages, but Home Fleet commander Adm. Bruce Fraser was already planning to lure the Scharnhorst into battle. Though the Royal Navy far outnumbered German surface combatants, it had to devote disproportionate resource to guard against possible sorties.

Fraser planned to use JW 55B as bait, reinforcing her ten escorting destroyers with three cruisers in “Force 1” under Vice Adm. Robert Burnett, which had just escorted a preceding convoy. Meanwhile, “Force 2” would sortie from the west, including the battleship Duke of York, the heavy cruiser Jamaica and four S-class destroyers.

The Brits made no effort to prevent German patrol planes from spotting the convoy on December 22. On Christmas Day, Fraser was pleased to learn that Scharnhorst and five destroyers had departed Altafjord at 7 p.m. under command of Adm. Erich Bay.

However, the German force failed to contact the nineteen-ship convoy. This far north, there was less than an hour of daylight, and gale-force winds were gusting heavy snowfall over the water. Bay fanned out his destroyers to extend his search—ultimately depriving his flagship of badly needed support.

At 9 a.m., the light cruiser Belfast of Force 1 picked up the Scharnhorst with her superior radar. The two sides finally spotted each other at a distance of about 7.5 miles and exchanged fire. While Scharnhorst missed, she was struck twice. One 8-inch shell fatefully smashed the battlecruiser’s forward-looking radar, crippling her situational awareness and the accuracy of her guns.

Scharnhorst disengaged, while the British escorts withdrew to screen the convoy as Force 2 raced to support them. But Bey circled Scharnhorst around and at noon bumped into Force 1 a second time. This time the battlecruiser’s guns twice struck the Norfolk, the huge 727-pound armored-piercing rounds passing clean through, knocking out a gun turret and radar.

Bey then decided to head south back to port with Force 1 in pursuit—though only the lighter Belfast could keep up.

However, the more numerous and powerful radars on Force 2’s Duke of York finally picked up the Scharnhorst twenty-five miles away after 4 p.m. Her sole forward radar knocked out, and nightfall and blizzard decreasing visibility, Scharnhorst was blind to the powerful British force barreling towards her from the west. Force 2 finally opened fire at six-miles range.

Norman Scarth, a sailor onboard the destroyer Matchless described the moment in a BBC interview:

All of us met up and all hell broke loose. Although it was pitch black the sky was lit up, bright as day, by star shells, which fired into the sky like fireworks, providing brilliant light illuminating the area as broad as day.

One huge fourteen-inch shell jammed the in Anton turret, silencing its triple-guns. Another strike triggered an ammunition fire in Bruno, forcing the gun crew to flood the turret to avoid an explosion. Now only Caesar could return fire—and fire she did, in turn knocking out a radar on the Duke of York.

However, the superior British fire-control radars gave British warships greater accuracy, while their flash-less charge left them difficult to spot with the naked eye.

Bey tried tacking back north away from Force 2, only to run afoul of the cruisers of Force 1. The battlecruiser finally began pulling away eastward at maximum speed. However, a long-range fourteen-foot abruptly penetrated Scharnhorst’s belt armor and blew apart one of her boiler rooms, reducing her speed to just twelve knots. Bey radioed his superiors “We will fight on until the last shell is fired.”

As the British barrage relentlessly crippled Scharnhorst’s main guns, smaller British destroyers swarmed in to attempt torpedo runs. Some of Scharnhorst’s smaller guns remained active, though, and one blasted a shell straight through the fire control tower of the Saumarez, killing eleven crew. Meanwhile, the Savage and Norwegian destroyer Stord dashed up to within a mile of the beleaguered battlecruiser and slammed three twenty-one-inch torpedoes into her port side approaching 7 p.m.

For nearly an hour more, the British ships relentlessly pounded the crippled Scharnhorst, with shells and torpedoes. The latter were known to occasionally sink capital ships with just a few lucky hits. The Scharnhorst, however, sustained nineteen torpedoes before she finally capsized.

As Scarth recounted:

She looked magnificent and beautiful . . . She was firing with all guns still available to her. Most of the big guns were put out. They were gradually disabled one by one. As we were steaming past at full speed a twenty-millimeter cannon was firing tracer bullets from the Scharnhorst.

A twenty-millimeter cannon was like a pea-shooter compared to the other guns and it could have no part in this battle . . . And that’s one of the things that remains in my memory—a futile gesture but it was a gesture of defiance right to the very end.

Afterward, Matchless and Scorpion picked up just thirty-six survivors from the freezing Arctic waters before receiving the order to abandon the rest for fear of a counterattack.

German battleships never engaged their British peers again in battle. Fifty-seven years later, a Norwegian-led expedition located the Scharnhorst’s mangled wreckage 290-meters deep on the seafloor.

Sébastien Roblin holds a master’s degree in conflict resolution from Georgetown University and served as a university instructor for the Peace Corps in China. He has also worked in education, editing, and refugee resettlement in France and the United States. He currently writes on security and military history for War Is Boring.

Image: Wikimedia Commons.