RAH-66 Comanche: Why America’s Stealth Helicopter Never Got Off the Ground

Despite a $7 billion investment, the Comanche never entered production—and frankly, never even came close.

Why doesn’t the United States operate a stealth helicopter? It’s not for lack of trying.

In the world of aerospace, stealth technology has become something of a prerequisite for new designs—at least with respect to American fighters and bombers. Ever since the F-117 Nighthawk, the world’s first stealth aircraft, debuted in the late 1980s, American designers have been incorporating stealth technology into military platforms. Indeed, every fighter or bomber that has been unveiled since the F-117 has featured stealth, from the B-2 Spirit to the F-22 Raptor, F-35 Lightning, and the upcoming B-21 Raider. The reason being that modern air defense systems are sophisticated enough to detect and destroy non-stealth aircraft—so stealth is required to creep behind enemy lines or to operate in contested air space.

Yet, despite being a staple of modern fixed-wing aircraft, stealth technology has not become a staple of rotary-wing, or helicopter, aircraft. And that’s not to say that rotary-wing aircraft do not perform functions in which stealth would be an asset; they do. Helicopters are used for special operations, insertions, extractions, recon, and attack and most certainly would benefit from being able to avoid radar detection—which is why the Pentagon funded a stealth helicopter program, known as the RAH-66 Comanche.

Inherent Problems

Whereas fixed-wing aircraft have readily been adapted to lower their radar cross section (RCS), that is, to make them stealthy, helicopters are much more difficult to “stealth.” Consider the helicopter. One massive rotor whirring overhead. A second rotor dictating yaw. A bulbous fuselage, prone to intense vibrations. A high-decibel turbine exhaust system. Operating low to the ground, the helicopter is simply not well suited for traveling undetected. Consider your own experiences. Fixed-wing aircraft fly overhead constantly barely demanding your attention. But you probably stop what you’re doing and watch whenever a helicopter approaches.

Still, the Pentagon recognized the tremendous upsides of a stealth helicopter platform and invested accordingly, despite the inherent problems. The investment resulted in the RAH-66 Comanche; a helicopter built with the hopes of replacing the OH-58 Kiowa. The investment was sizeable, at $7 billion dollars between 1996 and 2004. The results, however, were middling.

Testing the Comanche

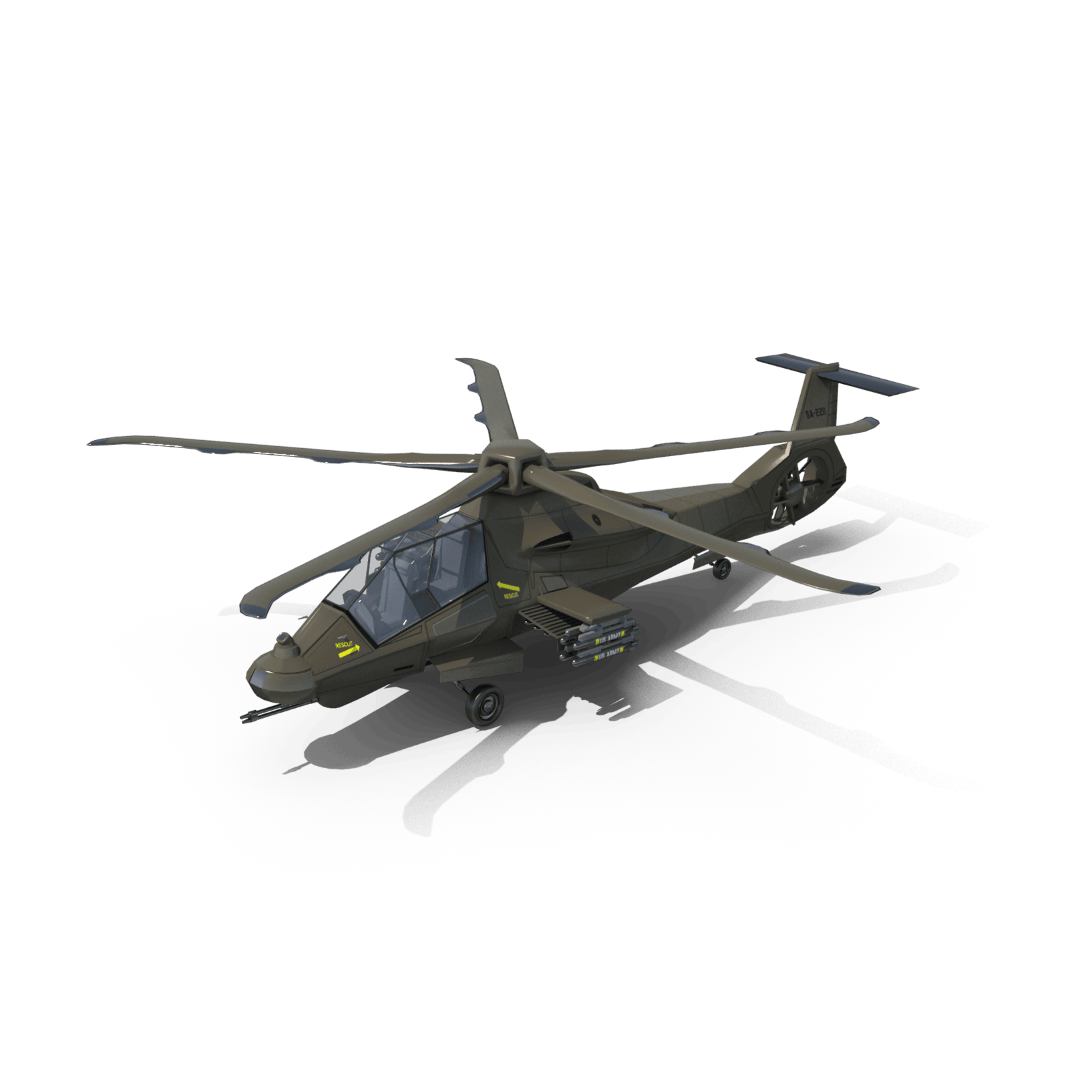

Two Comanche helicopters were built. They looked like what you would expect a stealth helicopter to look like—like something out of a science fiction film. The Comanche featured a smooth fuselage, Radar-Absorbent Material (RAM) coatings, and infrared-suppressant paint in a matte black finish. The stealth helicopter was also built with a fully composite rotor, which was designed to make less noise than the average helicopter rotor.

But despite a $7 billion investment, the Comanche never entered production—and frankly, never even came close.

Writing for TIME, Colonel Dan Ward noted that “many other aspects of Comanches technology were deemed too risky (i.e. immature i.e. hadn’t actually been developed i.e. didn’t exist)” and that testing had revealed “serious technical challenges in the areas of “software integration and testing of mission equipment, weight reduction, radar signatures, antenna performance, gun system performance, and aided target detection algorithm performance.” So, in sum, Ward wrote with biting snark, “Aside from the electronics, the software, the weapon system, the engines, and the overall weight, apparently everything else was fine.”

About the Author: Harrison Kass

Harrison Kass is a senior defense and national security writer with over 1,000 total pieces on issues involving global affairs. An attorney, pilot, guitarist, and minor pro hockey player, Harrison joined the US Air Force as a Pilot Trainee but was medically discharged. Harrison holds a BA from Lake Forest College, a JD from the University of Oregon, and an MA from New York University. Harrison listens to Dokken.

Image: Shutterstock-Pixelsquid / Shutterstock.com