Why Do Donald Trump and Millions of Americans Think Climate Change is a Lie?

2019 will not be remembered as the year when the world finally united to save the planet. Despite massive worldwide demonstrations and increasing global awareness and anxiety, the December 2019 UN Climate Change Conference (a.k.a., COP25) in Madrid failed spectacularly.

The reason? A handful of countries blocked significant action, in particular the United States, Brazil, Australia and Saudi Arabia, while China and India conveniently used the pretext of the historical responsibility of rich nations as an excuse for doing nothing.

A month before the COP25, President Trump formally confirmed the exit of the United States from the Paris climate agreement – just one policy change among more than 90 others aimed at rolling back environmental regulations. Because the United States is still the most powerful country in the world whose president has the most media coverage, this has created a toxic “Trump effect” that has weakened the credibility of international commitments and emboldened others, especially populists and nationalists, to shirk their responsibilities.

But how much do the aggressively anti-environmental actions of a minority president actually reflect American public opinion?

The US versus the rest of the world?

Even though Americans are less likely to be concerned about climate change than the rest of the world (by at least about 10 to 20 percentage points), a majority (59%) still see it as a serious threat – a 17-point increase in six years (Pew Research). But the devil is in the details. Only about 27% of Republicans say climate change is a major threat, compared with 83% of Democrats, a 56-percentage point difference!

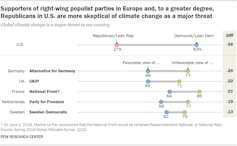

Climate skepticism/denial exists in other Western democracies, mostly among right-wing populists, but even by comparison, the American Republicans are the least likely to see it as a major threat.

This in turn raises another question: why are American Republicans more skeptical about climate change than right-wing voters in other countries? The first reason has to do with polarization in politics and identity.

Polarization

American polarization has deep roots in racial, religious and ideological divisions and can be traced back to the reaction of conservatives to the cultural, social and political transformations of the 1960s and 1970s. This polarization eventually made its way into politics in the 1980s and, even more so, in the 1990s when it became a ‘culture war.’ As global warming emerged on the US national agenda, it became one of those divisive hot-button issues in the culture war, along with abortion, gun control, health care, race, women and LGBTQ’s rights.

The fact that progressive Democrats took on the issue of global warming early on – former vice president Al Gore was a leading voice on the issue – and that the solutions they offered had to do with statist measure such as carbon taxes, a cap-and-trade system, or energy rationing resulted in further politicization of the issue.

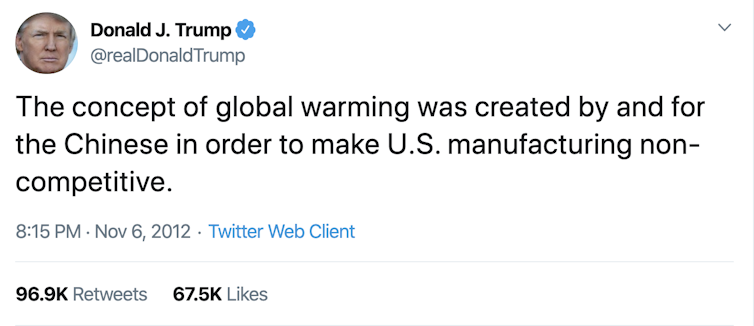

In 2001, then-president George W. Bush withdrew from the Kyoto protocol asserting that it would be too costly for the US economy. And in 2010, the Tea Party movement solidified Republican hostility toward the climate-change issue, preventing Congress from passing a cap-and-trade bill. It came as no surprise then when Donald Trump’s comment that climate change was a “concept created by the Chinese” to make “US manufacturing non-competitive” did little to damage his 2016 presidential campaign.

Indeed, his criticism of the Paris accord as being “very, very expensive”, “unfair”, “job killing” and “income-killing” clearly resonated with his electorate.

As much as Donald Trump’s political strategy has been to intensify polarization and to appeal to his base, he is more the symptom than the deeper cause of this polarization. Undeniably, the measures needed to curb greenhouse-gas emissions imply government intervention and internationally binding treaties that go against the conservatives’ ideals of individual freedom, limited government and free markets.

Trust and mistrust

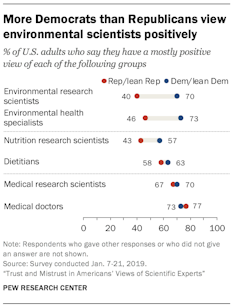

More than most other issues, our acceptance of the human impact on climate change is contingent on our trust in science and environmental scientists. For most of us, It is a matter of trust and not intelligence since we cannot do the science ourselves. Americans of all stripes generally trust scientists (86%), except for environmental research where there is a 30-point gap between Republicans and Democrats, a gap – more surprisingly – that is persistent among those with high science knowledge.

Trust in government is also highly partisan, but Republicans have tended to be more specifically wary of international institutions. For instance, only 43% of Republicans have a favorable view of the United Nations compared to 80% of Democrats. There are fringe conservatives, like Alex Jones or members of the John Birch Society the alt-right who want to “get out of the UN.”

In many ways, Donald Trump’s “America first” nationalist slogan is a rejection of international institutions, internationalism and cosmopolitanism – something he made clear at the the 73rd Session of the United Nations General Assembly in 2018.

Anti-intellectualism and anti-science

Americans have always tended to distrust the government, the elite and expertise. This is nothing new. In his 1964 Pulitzer Prize winning book, Anti-Intellectualism in American Life, Richard Hofstadter identified two sources of American anti-intellectual sentiment: business, which he depicted as unreflective, and religion, particularly evangelicalism. With its market-oriented, pro-business, and pro-religious agenda, the Republican party is naturally more distrustful of intellectuals and academics, including scientists.

This is fertile ground for right-wing think-tanks and lobbyists to sow doubt in the minds of conservatives who have a cognitive bias against climate change. And there has been no shortage of those, from the Global Climate Coalition, the Koch brothers to the Cato Institute, the Heritage Foundation, the fossil-fuel industry or the Heartland Institute. In Merchants of Doubt, Naomi Oreskes and Erik M. Conway have shown how these groups use a strategy questioning scientific research similar to that used by the tobacco industry in the 1970s and 1980s.

For a long time, these pressure groups allies in the American press that more often portrayed climate science as “uncertain” than the press in other developed nations. More significantly, Fox News has been the true echo chamber of climate-change deniers. The result is that Fox News viewers are less likely to accept the science of global warming and climate change. And now, the social media have only made the situation worse. A recent study found that videos challenging the scientific consensus on climate change were outnumbered by those that supported it. Then there is Donald Trump who has, since becoming president, attacked the scientists in his own administration by censoring their findings, shutting down government studies and pressuring scientists (full report available here) to reflect his own thinking on the issue.

Confronted with the reality of natural disasters and rising temperatures, most Republicans no longer deny climate change, rather they deny that humans are responsible, and warn that it will affect the economy.

The Frontier myth of an endless economic bonanza

When confronted by journalists about climate change, President Trump diverts the questions by focusing on the immediate benefits are more concrete than potential, vague, long-term gains, as he did during his news conference with President Macron of France in Biarritz, in August 2019.

This idea that nature offers vast untapped reserves that will yield perpetual and painless growth is evocative of what historian Richard Slotkin called the Frontier’s “bonanza economics”. It is an old American story that back to the Puritans: that the wilderness had to be conquered and transformed, that the Anglo-Saxon race was defined by its ability to exploit it, which also justified the displacement of indigenous people who did not work the land.

In this story, the president becomes the Frontier hero who ventures into the wilderness (of nature and politics) to transform it. His professed love for “beautiful clean coal” not only pleases his voters in coal-mining states, it also taps into the belief that nature is first and foremost an infinite provider of wealth that will contribute to the prosperity of all Americans. From Alaska to Minnesota, the Trump administration is all about easing restrictions on drilling, logging and mining at the expense of the protection of the land.

Yet there is another quintessentially American approach to nature. One that sees the presence of the divine in nature and has acknowledged the exhaustability of land and resources. One that is reflected in the writings of Ralph Waldo Emerson, and Henry David Thoreau, in the paintings of the Hudson River School, and in the activism of John Muir. It is also ingrained in the politics of Theodore Roosevelt, who used the ethos of the Frontier for his conservationist policies. If values trump facts, maybe this is the American story that today’s conservatives should embrace.

Jérôme Viala-Gaudefroy, Assistant lecturer, Université Paris Nanterre – Université Paris Lumières

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Image: Reuters