Why We Shouldn't Fight Over What Children Are Taught in School

Is there a better way?

In 2005, the Dover Area School District in Dover, Pennsylvania, was experiencing what might be called a civil war. As ABC News reported, “Dover was at war with itself”:

Townspeople would attack each other in ways they never had before….ABC News went to Dover to tell the story, but found that a lot of people were not talking — not to us and not really to each other. Depending on which side they were on, some people had come to believe that anyone who disagreed with their views was either ignorant or quite possibly evil, and that explaining themselves only gave their enemies more ammunition.

What caused this misery? The public schools, the very institutions that “father of the common school” Horace Mann said would create harmony, fostering “a general acquaintanceship…between the children of the same neighborhood….[Where] the affinities of a common nature should unite them together so as to give the advantages of pre‐occupancy and a stable possession of fraternal feelings….”

Specifically at issue was the teaching of the development of life on Earth, a topic that inescapably implicates deep‐seated religious beliefs, and that for many requires either that only creationism or evolution be taught. As ABC News explained, “The argument in Dover is of a special kind, where to let the other side win a little is to lose your own cause entirely.”

Public schooling — in which diverse people are required to pay for a single system of government‐run schools — inherently sets up such “special” conflicts. When two things cannot be simultaneously taught as true, or different values dictate different polices, one side must win, and the other lose.

Alas, such conflicts, while not always as destructive as Dover’s, are not particularly rare. In 2005 — the same year as the Dover battle — Cato’s Center for Educational Freedom began collecting examples of conflicts like Dover’s, pitting diverse values, or other intensely personal matters such as racial identity or culture, against each other. The intent was to illustrate that assuming public schooling will create harmony is dangerous, even if it is widely accepted. Indeed, it makes little logical sense: as we’ve learned from history, people do not happily sacrifice the things that make them who they are.

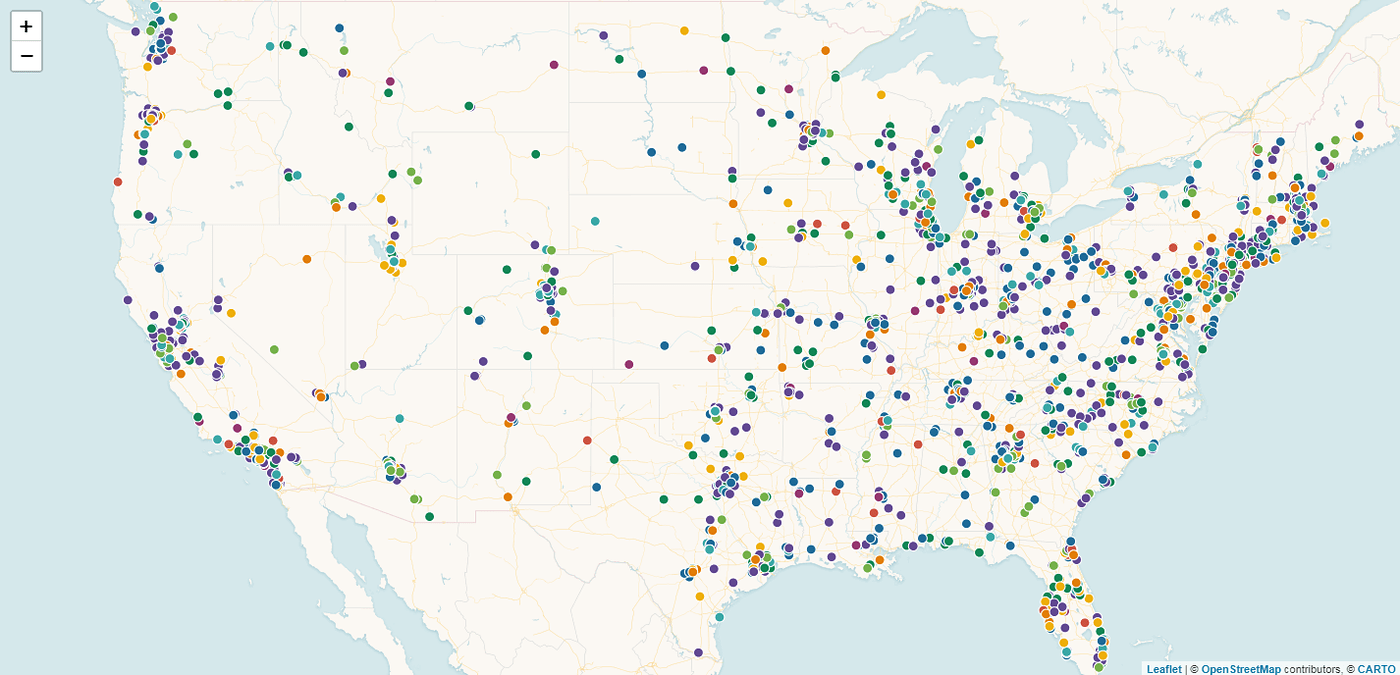

The end product of that initial collection was the report “Why We Fight: How Public Schools Cause Social Conflict.” Later, as we continued to collect conflicts, we decided to put our growing database on the Web, in searchable map form, so that wonks, reporters, and members of the public could see the kinds of very personal battles being fought in public schools, and get a sense that neither side is absolutely “right” nor “wrong,” but all are following their beliefs about what is right. We also wanted people in districts experiencing conflicts, and reporters covering them, to be able to locate places that may have suffered similar conflicts, and perhaps learn how they were ameliorated.

Unfortunately, about nine months ago the application we had been using to generate Cato’s Public Schooling Battle Map was phased out, and ever since we have been working to replace it. But today, in the midst of National School Choice Week, we are ecstatic to report that the new Map is up and running! It is not perfect — we will be adding more features soon — but it is working once again.

The Map contains 2,267 conflicts in thousands of districts and every state. Often the battles are centered at the state level, where everything from sex education standards to history curricula may be determined, meaning no one in the state can escape the conflict. And while the districts on the Map represent only around 9 percent of all districts, they contain roughly 44 percent of the country’s total student population. This is likely a function of our primary information source being media reports, and media tending to be concentrated in places with more people. There are also doubtless some people unhappy with school policies or curricula who do not formally complain, or if they do no reporter hears about it. The Map, then, is at best a baseline of conflicts, not a comprehensive view.

What does this have to do with school choice? Choice is fundamentally different from public schooling; its basic structure is far more conducive to peace and equality. Rather than forcing diverse families and communities to control a single system to get what they want taught, choice enables everyone to seek out what they need and desire. Rather than forcing everyone into a political arena, it lets them peacefully coexist.

Hopefully the Map will reach many eyes, and help people realize that one side winning and the other losing, or maybe both having to sacrifice cherished parts of themselves, should not be the only possible outcomes when people disagree. Especially, we hope that reporters will use the Map, and write more articles like the too‐rare ABC News piece with which this post started. Articles that focus not just on the two sides, like reporting on a boxing match, but that delve into the nature and underlying causes of the conflict. Maybe even articles that turn a spotlight directly on the zero‐sum nature of public schooling. Because there is a more equal, more peaceful, way to structure an education system: school choice.

This article by Neal McCluskey originally appeared in the CATO at Liberty blog in 2019.

Image: Reuters