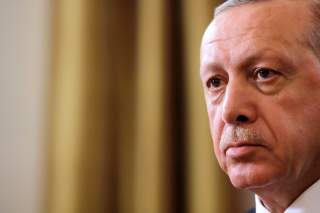

Can Erdogan's New Powers Help Fix Turkey's Economy?

Smart policies and quick decisions are needed in Ankara.

Turkey is suffering through its worst economic crisis since 2000, and it is at risk of a significant economic meltdown if appropriate emergency policies are not adopted soon. The Turkish lira has suffered a sharp devaluation in recent months because of Turkey’s rising external debt and loss of confidence in its ability to service this debt in the short run. The lira’s decline was accelerated after August 10 as a result of the deterioration of relations between Turkey and the United States. President Trump showed his frustration with Turkey over many diplomatic issues by doubling tariffs on Turkish metal exports, and this unexpected step triggered a lira sell-off.

To avert an economic catastrophe, similar to what happened to Greece in 2016 and more recently in Venezuela, Turkey must introduce very painful fiscal and financial reforms. How President Recep Erdoğan handles this crisis will most likely define the legacy of his political leadership as prime minister and then president since 2002.

More significantly, it will be the first test of how the new presidential government system. That new system was approved in April 2017 and implemented after the June 2018 presidential and parliamentary elections. The question is whether it can prove useful in managing a significant economic crisis.

President Erdoğan and his AKP party campaigned hard for approval of the constitutional reforms in the April 2017 referendum on the promise that a presidential system will bring more political and economic stability to Turkey. They argued Turkey had suffered severe economic instability under its parliamentary system before the electoral victory of AKP party in 2002, because of weak coalition governments were unable to impose fiscal and monetary discipline. The presidential system, it was argued, will be more capable of resisting populist pressures and factional politics that lead to high fiscal deficits and inflation rates.

In that referendum, the voters approved sweeping political reforms, which abolished the post of prime minister and enhanced the powers of the presidency. It also paved the way for direct presidential elections. After that victory, Prime Minister Erdoğan called for the country’s first presidential election in June 2018, which he won.

The Economy is in Trouble

Even when President Erdoğan was forming his new cabinet after the June election the signs of economic trouble were visible. The government's credit-based growth strategy triggered Turkey’s strong economic growth in recent years. As prime minister for more than thirteen years, Erdoğan encouraged and facilitated large borrowings by firms and households to finance a massive construction boom. Thanks to low-interest rates and easy credit policies of the U.S. Federal Reserve, Turkish firms and banks borrowed large sums in U.S. dollars and euros under the expectation that the underlying projects will be profitable and they can easily service their debt.

As the volume of Turkish firms' hard currency debt increased to alarming levels, experts inside and outside of Turkey called on the Turkish government to prevent excessive borrowing and stabilize the lira. President Erdoğan ignored these warnings and insisted that interest rates must be kept low to sustain strong economic growth. The Turkish Central Bank has increased interest rates since 2017, but so far the rate hikes have not been large enough to stop the devaluation of lira.

The lenders and investors were alarmed by this policy and the steady increase in Turkey’s external debt. These concerns led to capital flight and a gradual devaluation of Lira, which made it even more difficult for the Turkish firms to repay or refinance their debt. When lira-dollar exchange rate was three lira per dollar, a firm with a $10,000 annual interest charge obligation had to raise 30,000 lire. When the exchange rate rose to five lire per dollar, $10,000 became the equivalent of 50,000 lire which was much harder to raise.

The rising borrowing costs have already pushed many Turkish firms (particularly in the construction industry) into bankruptcy, and the government has also suspended funding for several mega-projects in recent months. These budget cuts for major public projects, such as the new Kabatas “seagull” ferry terminal, are caused by lack of fiscal revenues and a desire to contain the fiscal deficit. Turkey’s economic agenda for the coming months also includes a freeze on most government investment projects.

There are now clear indications that the Turkish economy has reached a crisis point, which requires immediate attention. The Lira has suffered a 40 percent devaluation since January 2018, and this sharp devaluation has increased the annual inflation rate to near 18 percent in August.

As a result of the excessive borrowings of past fifteen years, Turkey’s total foreign debt (owed by both public and private borrowers,) is close to $500 billion and $230 billion of this sum must be refinanced or retired in the next twelve months. These short-term hard currency obligations might put many firms at the risk of default. Furthermore, many firms might have to reduce output or suspend operations altogether because of the high costs of imported materials and their inability to pass the rising costs to their customers.

This situation has led to a sharp recession in the construction and real estate sector, which has served as the primary driver of Turkey’s economy in the past decade. But most experts believe directing so much financial resources to the real estate sector was a mistake. As economic weakness spreads to other sectors, the households that are currently suffering under high inflation rates are likely also to face rising unemployment. The credit-financed economic boom resulted in a 7 percent annual economic growth rate in the first quarter of 2018, but economists warn that the economy is at risk of experiencing a deep recession in 2019.

Managing the Crisis Under the Presidential System

There were many steps that the Turkish government could have taken in the past three years to avoid the current external debt crisis. It was also possible in the past six months to prevent the rapid devaluation of lira by a combination of higher domestic interest rates (which were repeatedly recommended by economists and the International Monetary Fund) and better management of diplomatic disputes with the United States. These steps were not taken, and Turkey has come face to face with one of the worst economic crisis of its modern history. There are no pain-free options for confronting this crisis.

The most immediate required step by President Erdoğan is to stop the devaluation of lira. In the medium term, he must find an effective strategy to reduce new borrowing and help Turkish firms with their refinancing needs. Simultaneously, the Turkish government must keep the deficit low by cutting government spending to manageable levels in comparison to government revenues.

These are not easy choices, and the practical steps toward these goals will have adverse effects on millions of Turkish households. The government will have to let public sector wages rise less than the rate of inflation, resulting in a reduction in standards of living for public sector agents. High-interest rates will also raise the costs of borrowing for families and businesses.

Turkey faced similar types of economic crises several times before 2002, particularly in the 1990s. The unpopularity of required measures and reluctance of former governments, under Turkey’s parliamentary system, to pay the political price for implementing them, was the main reason that substantial economic reforms were often postponed or abandoned halfway. As a result, Turkey’s inflation rates in some years approached 100 percent. There is no denying that Turkey’s parliamentary political system had a poor performance in achieving fiscal and monetary discipline. The country frequently suffered from large fiscal and current account deficits and had to request external assistance from the IMF and Western governments to meet its debt obligations. (Turkey also frequently benefited from financial support by the United States and European countries because of its strategic value as a North Atlantic Treaty Organization ally in the Middle East and the Black Sea region.) There was also more economic stability and better economic growth under AK party of President Erdoğan since 2002. But it is now clear that this success had been made possible by excessive borrowing, which has led to the current debt crisis.

President Erdoğan and his economic team are facing the current crisis under a different political system, which has granted many new powers to the president.

Many of these new powers are directly relevant to overcoming the current crisis. The most important advantage of the new system is that the executive branch is less vulnerable to short-term populist pressures. The president is now the head of the government and can directly appoint the cabinet ministers. Moreover, the president’s cabinet is no longer vulnerable to a parliamentary vote of no-confidence. Furthermore, his five-year presidency is more secure regardless of fluctuations in public opinion. For example, to call for an early election, the parliament now needs a 60 percent support as opposed to a simple majority. The impeachment process is also more difficult and less likely to succeed under the new presidential system. This secure tenure makes it easier for a Turkish president to implement painful economic reforms that require two to four years to be effective. If a president is committed to these reforms, he or she does not have to worry about being undermined by unexpected early elections under populist pressure.