Iran Policy and Misusing the Fear of Terrorism

The Trump administration is manipulating the terrorism issue to stir up as much hatred as possible against Iran.

The history of U.S. administrations manipulating the issue of terrorism for purposes unrelated to terrorism predates Donald Trump’s presidency. One reflection of this history is the official U.S. list of state sponsors of terrorism, which has never tracked very closely with the reality of specific states being complicit or not complicit in international terrorism. Some complicit states have never appeared on the list because they were considered U.S. friends or allies—such as Saudi Arabia with its nurturing of Sunni radicalism, Pakistan with its support to extremist groups in Afghanistan, or left-wing governments in Greece that condoned radical leftist terrorism. Other states have been taken off or put on the list to send messages on topics other than terrorism. Iraq, for example, was taken off when the United States was tilting toward Iraq during the Iran -Iraq War, then returned to the list when Iraq invaded Kuwait. North Korea was belatedly taken off the list ten years ago and put back on last year, again not because of any change in terrorist behavior but for other reasons—in this case having to do with the objective of denuclearization.

The most flagrant and damaging manipulation of the issue of terrorism was the George W. Bush administration’s exploiting of American outrage over 9/11 to muster support for the Iraq War by conjuring up an “alliance,” which in fact never existed, between Saddam Hussein’s regime and Al Qaeda. The promoters of that war went so far as to establish a staff effort inside the Pentagon to discredit relevant work of the U.S. intelligence community, which had correctly concluded that there was no such alliance.

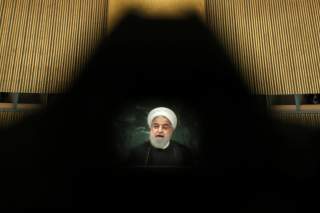

Now the Trump administration is similarly manipulating the terrorism issue. The administration wants to stir up as much hatred as possible against Iran rather than to convey an accurate picture of international terrorism today and where and how Americans are most likely to fall victim to it. This was evident in the rollout last week of the latest edition of the congressionally mandated annual report on international terrorism.

Past Involvement

Iran certainly has done terrorism and has given good reasons to be placed on the list of state sponsors, although one must reach back into an ever-receding past to find those reasons. (Saddam Hussein’s Iraq also had done some real terrorism, but not with Al Qaeda.) The first big encounter between the United States and the new Islamic Republic of Iran was a major act of terrorism: the taking of hostages at the U.S. Embassy in Tehran in 1979. Also early in the Islamic Republic’s history, Iranian assassins periodically killed dissident Iranian expatriates in Europe and elsewhere, but those murders ceased years ago. The last time Americans became victims of an incident that meets the State Department’s legally codified definition of terrorism (which involves violence against noncombatants) and in which Iran probably played a role was more than two decades ago: the bombing of the U.S. military installation at Khobar Towers, Saudi Arabia in 1996. (The U.S. servicemen who were the targets of that attack were deemed noncombatants because they were resting in their barracks at the time—although some observers skeptical of this coding note that the servicemen were part of a larger military mission.)

The phrase “leading state sponsor of terrorism” has become a label that rolls easily and automatically off the lips of Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and other U.S. politicians. The label has become an almost di rigueur attachment to any American mention of Iran. As with other such labels that are automatically invoked, this one has become a substitute for, rather than an accompaniment to, careful attention to facts and evidence.

The administration’s attempt to paint Iran as a major problem in international terrorism is badly misleading. This is readily apparent in looking at any picture of terrorism that includes the groups that have to be in the center of that picture—Al Qaeda and the Islamic State or ISIS—and that necessarily are mentioned up front in the up-front part of the State Department report. Iran is on the opposite side from these groups on almost any political, ideological, and sectarian divide that matters. Iran also is on the opposite side from those groups on multiple Middle Eastern battlefields. This is true in Iraq, where Iran has provided more help than any other outsider in freeing western Iraq from the grip of ISIS. It is true in Syria, where Iran aids a Syrian regime that is now looking at the rebel redoubt in Idlib province in which the most powerful group and de facto local government is the Syrian affiliate of Al Qaeda. It is true in Yemen, where the Houthi movement that has received Iranian aid is one of the fiercest opponents of Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, the group that has come closest to accomplishing a post–9/11 mass-casualty attack in the United States.

Iran has paid a price for its opposition to these terrorist groups, most dramatically in June of last year, when an ISIS attack on the Iranian parliament and the mausoleum of Ayatollah Khomeini in Tehran killed seventeen civilians and wounded dozens more. An equivalent in the United States would be an ISIS attack on the U.S. Capitol and the Washington Monument. Against the backdrop of such a revenge attack, think of how inappropriate, not to mention outrageous, it would be to talk of the United States as being on the wrong side of international terrorism.

Stretching the Story

The Trump administration’s new terrorism report, and the accompanying pitch by Coordinator for Counterterrorism Nathan A. Sales, illustrate how much the administration tries to stretch the canvas to put Iran in the center of the picture of international terrorism. The administration reaches, for example, back into the past. Sales, in trying hard to come up with any specific incidents, mentioned an attack attributed to Lebanese Hezbollah against an Israeli tourist bus in Bulgaria in 2012. (The State Department report, being annual, is supposed to describe current international terrorism, not just be a history of what happened years ago.)

The section about Iran in the portion of the report on state sponsorship of terrorism is unable to name any specific, current or recent, attack that Iran instigated or executed. The observations in that section, when not immersed in generalities such as “provide cover for associated covert operations, and create instability in the Middle East,” fall mainly in two categories. One includes references to Iran’s aid, partly furnished through supported militias, to sides it favors in a conflict such as the Syrian civil war. Of course, many other parties, including insiders as well as outsiders, are fomenting and executing grievous amounts of violence in that war. Most such politically motivated violence is open warfare—and as such will not show up in the State Department’s statistics about terrorism—even though, as with Saudi Arabia’s indiscriminate bombardment of Yemen, it kills far more innocent civilians than anything that does show up in those statistics.

The other principal type of observation concerns Iran’s alliances with groups such as Hezbollah and the Palestinian group Hamas. Those groups certainly have done terrorism, but they are much more than terrorist groups and are part of broader political conflicts and political systems where Iranian motivations for the alliances are to be found. Hamas won the last free and fair election held among Palestinians, and it represents the side in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict that most Arabs support (which is partly why Iran supports it as well). Hezbollah is one of the most important political actors in Lebanon, where it has seats in the legislature and has participated in governing coalitions.

The report states, without elaboration, that Iran “sponsored cyberattacks against foreign government and private sector entities.” When it comes to Iran and cyberattacks, occupants of the U.S. glass house probably need to be careful about throwing that stone in a report about terrorism, especially given the direction the Trump administration appears to be heading on that subject.

The report also states that Iran “remained unwilling to bring to justice” Al Qaeda members in Iran, with a further suggestion that Iran somehow had been facilitating that group’s operations. Left unstated is that Al Qaeda members who turned up in Iran were kept in a kind of house arrest, and that if Tehran did not turn them over to someone else it was because the Iranians hoped to use them as bargaining chips to bring to justice violent members of the cult/terrorist group known as Mujahedin-e Khalq, whose attacks (besides claiming American victims) have been responsible for years of bloodshed in Iran.

Sales stated, “The threats posed by Iran’s support for terrorism are not confined to the Middle East; they are truly global,” and made reference to “caches” of weapons and explosives in disparate places. Regardless of this assertion, Iran is no global power and has consistently demonstrated that its interests are sharply focused on its own region. Violent actions it has taken or abetted farther abroad—going back to those assassinations of dissidents in the early years of the Islamic Republic—have been intended to meet what it sees as threats closer to home. Rather than Tehran looking for trouble far afield, any long-distance terrorism involving Iran has been in direct response to political violence that others have inflicted back in the Middle East. Hezbollah’s bombing of the Israeli embassy in Buenos Aires in 1992, for example, was in retaliation for Israel’s assassination of the group’s secretary general. Some other attacks against Israel-related targets early in this decade (including that bus bombing in Bulgaria) were attempts to respond directly to the serial assassinations of Iranian nuclear scientists. According to the State Department’s definition of terrorism, if not its policy-guided pronouncements, those assassinations were every bit as much terrorist acts as were the attempts to retaliate for them.