India Lost a War to China In Less Than a Month

Here’s What You Need to Know: The Chinese-Indian War still has implications for how each country views the other today.

In 1962, the world’s two most populous countries went to war against one another in a pair of remote, mountainous border regions. In less than a month, China dealt India a devastating defeat, driving Indian forces back on all fronts. Along with breaking hopes of political solidarity in the developing world, the war helped structure the politics of East and Southeast Asia for generations. Even today, as Indian and Chinese forces square off on the Doklam Plateau, the legacy of the 1962 resonates in both countries.

Who Fought?

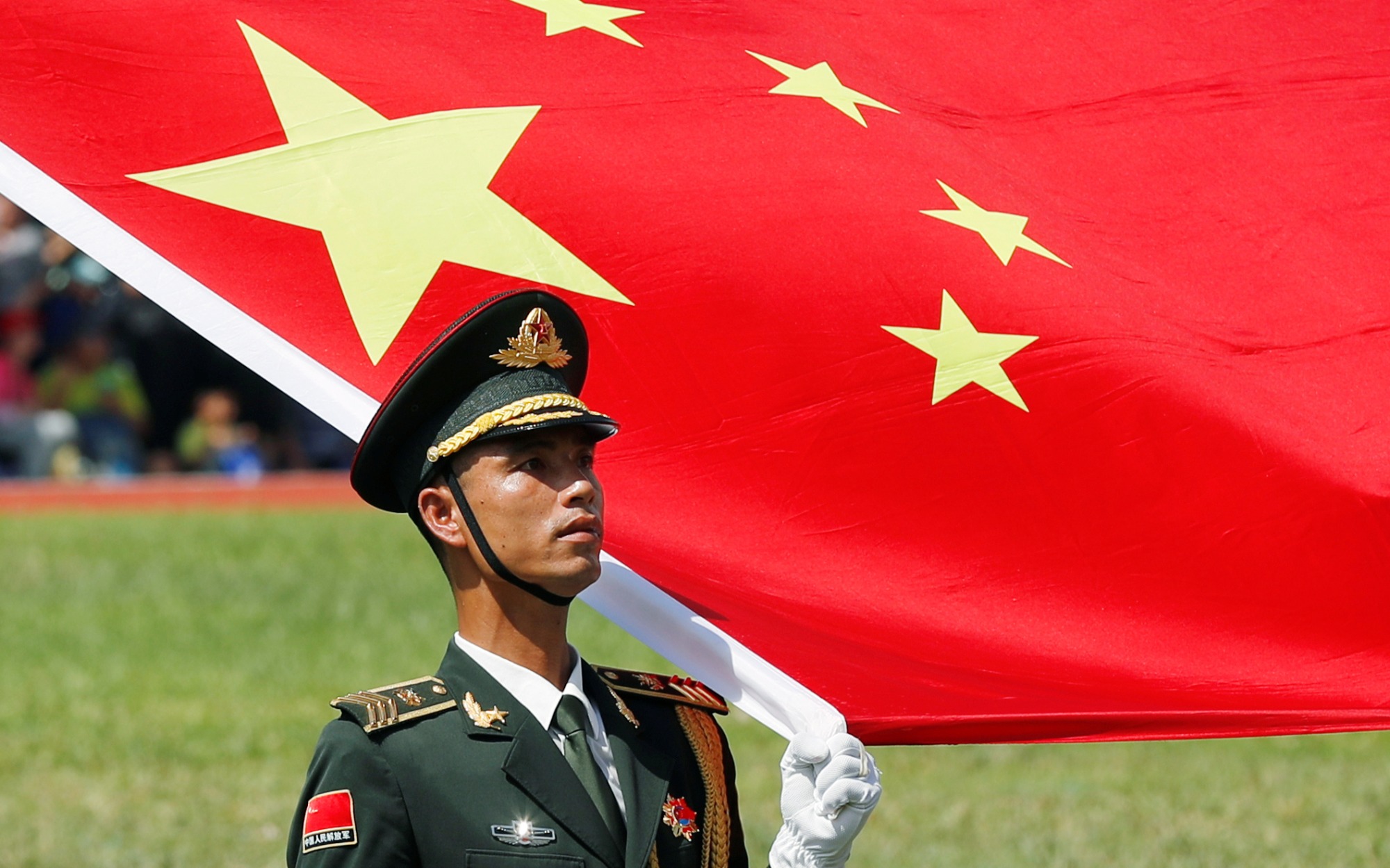

While both the Chinese and Indian governments were relatively new (the People’s Republic of China was declared in Beijing in 1949, two years after the India won its independence), the armed forces that would fight the war could not have been more different.

The Indian Army developed firmly in light of India’s imperial heritage. Large Indian formations had fought in several theaters of World War II, including North Africa and Burma. These forces would, in many ways, form the core of the new Indian military. The post-independence Indian armed forces were structured along lines broadly similar to that of India’s colonial antecedent, the United Kingdom, and in the early years operated mostly with Western equipment. This incarnation of the Indian Army saw its first action in the 1947, in the first Kashmir War, fighting against its erstwhile associates in the Pakistani Army.

The Chinese experience could not have been more different. The People’s Liberation Army (PLA) emerged as the military arm of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), a revolutionary organization with both urban and rural roots. The PLA experienced nearly twenty years of uninterrupted major combat operations after its creation, fighting bitter conflicts against the Nationalist armies of Chiang Kai-shek, then against the Imperial Japanese Army, and finally against the American-led UN coalition in Korea.

The war did not involve air or naval forces from either India or China. This worked in China’s favor; the Indian Navy was considerably superior to the People’s Liberation Army Navy at the time, and the Indian Air Force (equipped mostly with British and French fighters) had an advantage in modern equipment. Moreover, the PLA did not develop a competence in combined air-ground operations for another generation. However, poor coordination on the Indian part, combined with the forbidding terrain, prevented the extensive use of combat aircraft. A disinterest in escalation meant that the navy would play no role in the conflict.

Why It Was Fought

The immediate cause of the war was a territorial dispute between India and China along two sections of the border. The colonial-era demarcations between China and Tibet had left the disposition of certain sectors unclear, a development that would recur not only in modern Chinese history, but across the developing world, as newly independent countries began to flex their muscles. Numerous incidents occurred in the years before the war, usually resulting in light casualties on either side.

India deployed forces forward into territory claimed by China, and largely ignored both Chinese warnings about this deployment, and the massive Chinese troop buildup along the border. The causes of India’s poor preparation were a combination of political indifference and poor intelligence collection; the Indian government did not expect an attack (and was generally more focused on Pakistan), and the Indian Army and Air Force had little in the way of reconnaissance assets to detect and analyze the Chinese buildup. Most Indian units became aware of their Chinese counterparts only after coming under fire (sometimes from behind their own positions).

A related issue was China’s long-term concern over Indian subversion in Tibet. The Indian government maintained good relations with Tibetan exiles, and had provided a safe space for Tibetan insurgents. Some evidence suggests that Nehru expected to retain a degree of influence over political developments in Tibet, which was obviously a problem for China.

China may also have wanted to establish itself as the preeminent power in the region by giving India a bloody nose. The Cuban Missile Crisis provided a convenient (and completely unexpected) distraction, as both superpowers were more worried about each other than what the Chinese and Indians were doing at the moment. Finally, China also faced domestic discontent associated with the disastrous failure of the Great Leap Forward. Mao Zedong lost some control over domestic policy, but retained substantial control over foreign and military policy; a quick victory increased his prestige and power within the CCP.

How It Was Fought

On October 20, PLA forces launched coordinated offensives in both the eastern and western disputed territories. The Chinese offensives were coordinated but widely separated; the eastern theater was along the Namka Chu River (near Bhutan), and the western theater at Aksai Chin (near Kashmir). The locations were forbidding. The entirety of the war was fought in rugged terrain, at elevations exceeding ten thousand feet. This complicated logistics on both sides, and prevented the deployment of heavy equipment or quick reinforcements. This favored the Chinese, who had prepared their offensive carefully, and who had considerable experience with light-infantry operations.

Chinese forces quickly overwhelmed Indian forward positions in both areas. By October 24, Chinese infantry (with light artillery support) had cleared both disputed areas, driving Indian forces from the region. Chinese numerical advantages were substantial; in both theaters combined, and including reserves, the PLA had almost a seven-to-one advantage over the Indians. A lull in the fighting, along with some attempt at negotiations, ensued for the next two weeks. In mid-November the fighting began again, and again the PLA won significant tactical victories.

The fighting ended with a unilateral Chinese ceasefire on November 19. The PLA withdrew from the Indian territory that it had captured during the fighting, returning to positions that it had always maintained belonged to China. Many Indians, panicked by the defeat of forward elements in the mountains, expected a larger Chinese invasion. However, the PLA lacked the logistical capabilities necessary to sustain a large scale advance, which would have required a considerably greater degree of mechanization. Moreover, Beijing had no apparent interest in administering a significant portion of Indian territory.

What It Meant for the Future

In the short run, the war was undoubtedly a triumph for China, which had shown not only its strength, but also a degree of forbearance. The victory confirmed Chinese control of Tibet, and created the foundation for a strong relationship between Pakistan and China (the latter closely monitored Indian military performance during the conflict). On the Indian side, the shocking defeat severely damaged the government of Jawaharlal Nehru, and may also have worsened his health; Nehru died less than two years after the war’s conclusion. But the war also sparked a serious interest in military modernization in India, which helped lead to a strong relationship with the Soviet Union. Within a decade, the USSR would become a primary arms supplier for India. And the Indian military was undoubtedly better prepared during the 1965 and 1971 wars against Pakistan.

The war did not settle the fundamental issues that divided India and China, as Delhi has never agreed to the basic justice of Beijing’s position. However, it did demonstrate Chinese power and military effectiveness, which essentially closed the question of the militarized border for more than a generation. Both sides struggled with more important issues in the aftermath of the war. Within four years, Mao Zedong would embroil China in the Cultural Revolution, radically reducing the military readiness of the PLA. Relations between China and the USSR deteriorated, nearly to the point of war in 1969. India, as noted, became further embroiled in its long conflict with Pakistan, a situation that has not yet been resolved.

In an important sense, the issues now surrounding the confrontation on the Doklam Plateau are essentially the same as those that the two countries left unresolved in 1962. The balance of power may have changed, however, as has the geopolitical situation. Hopefully good sense will prevail, and Beijing and Delhi will avoid a repeat of the events of October 1962.

Robert Farley, a frequent contributor to TNI, is author of The Battleship Book. He serves as a Senior Lecturer at the Patterson School of Diplomacy and International Commerce at the University of Kentucky. His work includes military doctrine, national security, and maritime affairs. He blogs at Lawyers, Guns and Money and Information Dissemination and The Diplomat.

This article first appeared in 2017.

Image: Reuters