Want to Simulate World War III? Play This Game

Here’s What You Need To Remember: Like a real commander, the player can only place his troops in the most advantageous position and hope for the best.

Forget politics. Forget history. Who knows why the Soviets invaded West Germany in 1989? Perhaps it was a bad grain harvest in the Ukraine. Perhaps they feared the U.S. would strike first.

Or, maybe the Soviets simply decided—like many an empire or perhaps even a certain North American republic—that the only way to demonstrate they were not a declining superpower was by going to war.

What difference does it make now? The Soviet armored armada has just crossed the German border, racing for the Rhine and then the English Channel. And now it’s time to find out just what all the trillions of dollars and rubles sacrificed by the capitalist and the proletariat taxpayers actually paid for.

Flashpoint Campaigns: Red Storm, from Matrix Games, attempts to answer the biggest military what-if since 1945. What would have happened had the balloon gone up, the tripwire been tripped, and the Soviets had invaded West Germany in 1989?

How would a T-80 tank fare against an M-1 Abrams? A Soviet motorized rifle division against a U.S. armored cavalry regiment? These are the questions that make military buffs drool and made the late Tom Clancy a rich man.

It’s the war that—thank God—never was. By that time, both sides had fielded enormous numbers of advanced technologies, from stealth aircraft and reactive armor to night vision systems. Many of the tanks, infantry fighting vehicles, helicopters and missiles went on to fight in Desert Storm and are still in use today.

Flashpoint Campaigns: Red Storm is a 2-D tactical computer war game, where each hexagon on the map represents 500 meters, and maneuver units are platoons for NATO and companies for the Soviets. The scenarios typically pit a larger Soviet force—maybe a tank or motorized rifle division—against a weaker U.S., British or German brigade or two. The game can be played against the AI or another human, either by swapping seats at a single machine or trading the scenario file over e-mail.

Every good war game focuses on some distinctive factor in warfare. Flashpoint Campaigns: Red Storm focuses on the practice of command. Note the word is “practice, “not “art,” because the essence of the game isn’t devising a good plan. It’s hard enough to get your troops to execute a bad one.

Instead, how do plans go awry? And how can the player manage?

Many strategy games ignore the issues and problems of command, because it’s frustrating to players when their digital armies don’t instantly obey orders. Yet that’s not realistic. Replace couriers on horseback with radios, and command and control would still have bedeviled Group of Soviet Forces Germany and the British Army of the Rhine no less than it afflicted Julius Caesar and Napoleon.

How to manage a war

Flashpoint Campaigns: Red Storm simulates command and control by rationing that most precious commodity: time. The game is the embodiment of Richard Boyd’s famous OODA (observe, orient, decide, act) loop, in which the key to victory is achieving a tighter loop than your opponent, and thus a shorter decision cycle in which to respond to rapidly changing battlefield circumstances.

Both the NATO and Soviet players plot their moves secretly, which the game then executes simultaneously. At the beginning of the game, both players can freely issues orders such as hasty movement, deliberate movement or assault. But afterwards, a certain interval of time must pass before new orders can be given, and that interval is shorter for NATO.

Thus the Americans might order a tank company down a road to stop a Soviet attack, realize the attack is a feint, and after four minutes of game time have elapsed, have a chance to redirect its tanks toward the real attack. For the Soviets, 24 minutes of game time might elapse before they can redirect their tanks. Thus while the Soviets have the advantage of numbers, they must also plan ahead more carefully, and will be stuck with that plan for longer even if circumstances change. The game also imposes delays before a unit will actually execute an order, depending on factors such as the presence of radio jamming and whether the unit is under fire.

However, the command situation is fluid. Should NATO lose too many HQs, or should too many combat units suffer disorganization or be out of command range of their controlling HQs, then it will be NATO whose forces behave sluggishly.

A neat touch is that the more orders a player issues to his forces, the more his radio traffic level rises, and the greater the chance that enemy signals intelligence will detect the location of his units, especially headquarters units. As an added incentive to keep off the airwaves, artillery can be instructed to automatically bombard any detected enemy headquarters.

Which brings up the other fascinating aspect of this game, and that is fog of war, which is simulated here better than most games. Basically, in Flashpoint Campaigns: Red Storm, your troops get blown up and you don’t know exactly what did them in.

A thin, colored line flashes on the screen between your tanks and some woods a kilometer away, and your T-80s explode. Was it an Abrams or a Challenger tank that did them in, or an Apache helicopter, or an infantry platoon with anti-tank missiles? Without knowing the type of threat, it’s hard to defeat it. Often the only way to really be sure is to send in a very expendable reconnaissance unit, or get in close for an assault.

The emphasis of the game on command rather than combat may seem a tad dry to some who like more frenzied action. While players control the movement of their troops, combat is automatic, with units seeming to blast away at maximum range (making ambush harder).

Thus like a real commander, the player can only place his troops in the most advantageous position and hope for the best.

However, no Cold War tactical game could ignore hardware, and Flashpoints Campaign: Red Storm has plenty of it. The T-80, for example, is rated for front and flank armor protection, cannon, cannon-launched missiles, machine guns, laser rangefinders, reactive armor and smoke dischargers.

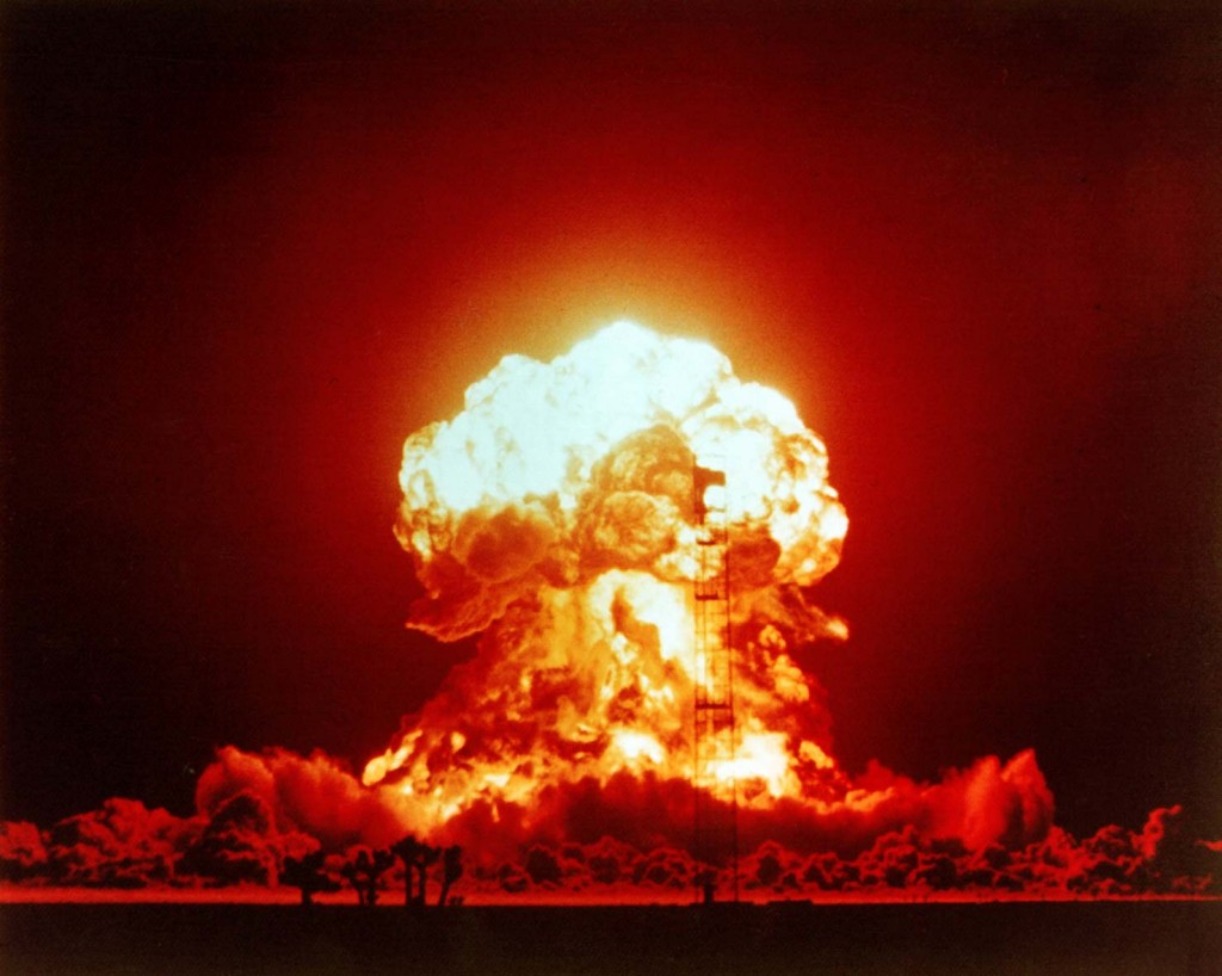

There are different types of sensors, artillery barrages and even chemical and tactical nuclear weapons. Equipment can be destroyed or damaged, and there are basic supply rules that impose a random chance that a unit will have to withdraw to the rear for resupply.

One lesson that penetrates like an armor-piercing round is how lethal modern weaponry and sensors are. The old saying “what can be seen can be destroyed” is made manifest in this game, where any unit, even under moderate cover, will eventually get picked off if it’s seen by the enemy. For all the advanced armor of an Abrams, the best protection for a tank is behind a ridge or a house.

Flashpoint Campaigns: Red Storm is not a flashy design, and those who want to delve directly into virtual combat are advised to try another game. Instead it illustrates Clausewitz’s dictum that in war everything is simple, but the simplest things are hard.

Had the Cold War turned hot, the friction of war would have burned bright.

This first appeared in War Is Boring here.

This first appeared earlier and is being reposted due to reader interest.