Will Turkey’s Coming Election Deliver a Pivot on Foreign Policy?

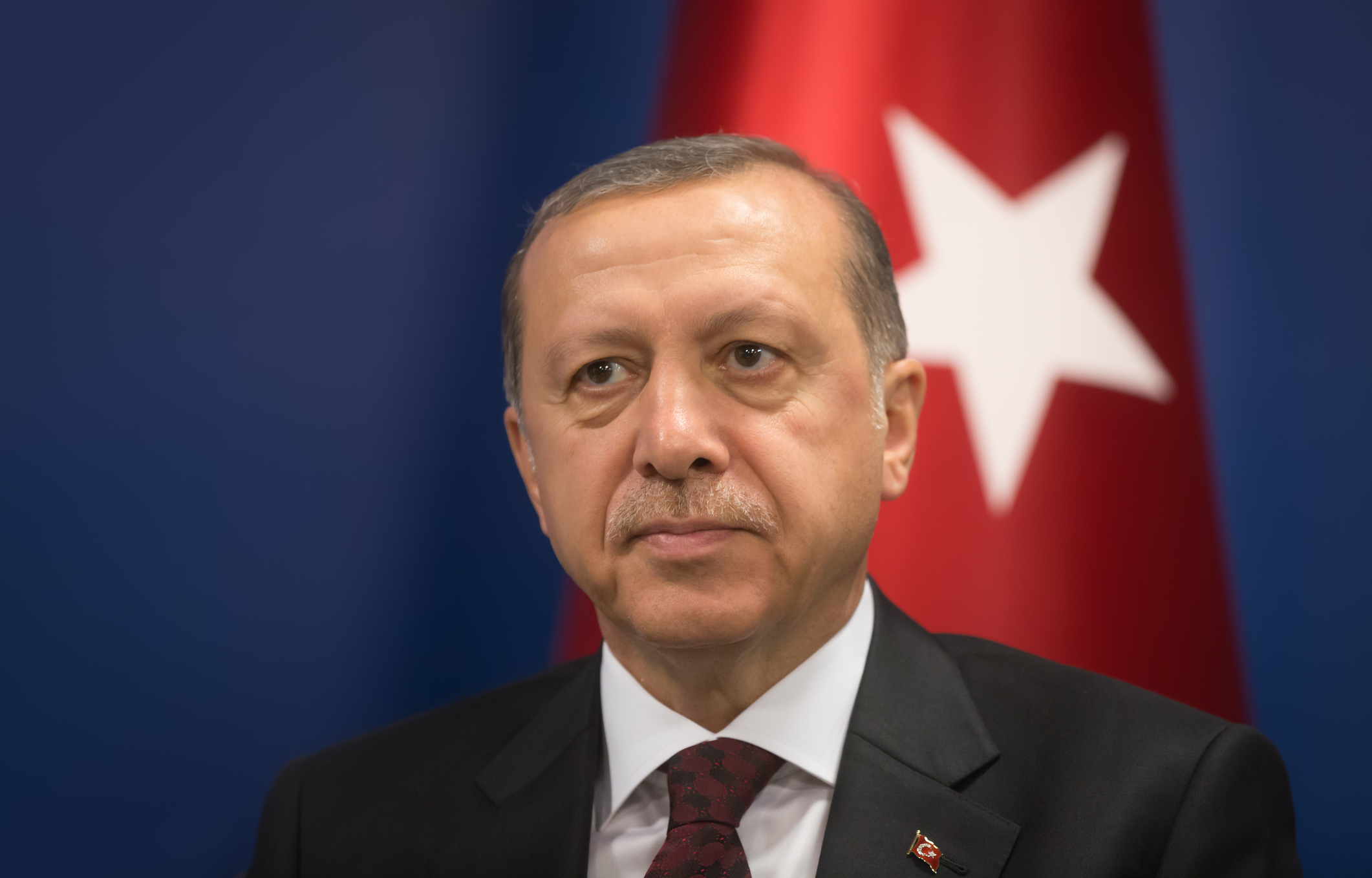

One of the world’s most important elections is scheduled to take place on May 14, with the twenty-year reign of President Recep Tayyip Erdogan facing a rare challenge—a potential final off-ramp for voters to reclaim their country’s democracy.

If rampant inflation and the soaring cost of living were insufficient motivations to drive voters to line up against Erdogan, the government’s ham-fisted and incompetent response to the catastrophic February 6 earthquake leaves no doubt that top-down power vested in a single individual does not serve the public interest.

On the other side of the ballot, a new bloc of six opposition parties, including the IYI Party and CHP, have nominated Kemal Kilicdaroglu to stand as their candidate for president. If they prevail, what should U.S. and European authorities, and other great powers, expect in terms of foreign policy changes?

Relations between Ankara and its Western allies have sunk to historic lows, with mutual antagonism featuring in nearly every area of cooperation—oftentimes worsened by unnecessary and irrational gestures. Much of the discussion of the relationship has been quite narrow, limited to disputes over F-16 sales, NATO expansion, and the conflict in Syria. Nevertheless, there are numerous mutual interests that could be promptly advanced by a new opposition-led government.

A NATO member, Turkey sits at an unusually important global crossroads, bridging West and East—and the country’s geostrategic location has only risen in importance with Moscow’s war in Ukraine.

There are clear indications that, should an opposition alliance sweep to power, the tone of diplomatic relations regarding Ukraine would shift. Meral Aksener, leader of the IYI Party, in addition to being a former interior minister and vice speaker of parliament, was one of the first Turkish politicians to denounce Russia’s rigged referendums in eastern Ukraine. Her staunch position is broadly supported by the Turkish people who have historically empathized with the Crimean Tatars.

Very early on, Aksener argued that Russia’s conduct represented “ a clear violation of the right to sovereignty which is the basis of international law, and that Putin’s adventurist behavior is not only a threat to Ukraine but to the security and territorial integrity of all countries in the region.”

To date, Turkey has not joined Western sanctions against Russia, but it has played an important role in brokering successful agreements, such as the Black Sea Grain Initiative. This is proof of the value of the U.S.-Turkey Strategic Mechanism. With Ankara likely to play a crucial role in future potential peace talks, it is critical that the next administration reflects a stronger rejection of the illegal invasion and occupation of Ukraine.

Most Turkish voters favor productive rather than antagonistic relations with Western allies. The public is historically weary of Russian expansionism, dating back to the Russo-Ottoman wars. Neither did Josef Stalin’s attempts to violate the 1925 Turkish-Soviet Treaty with his demands for military bases near the Bosporus Straits and attempts to annex territories such as Kars, Ardahan, and possibly areas of Erzurum and the Eastern Black Sea endear the Turkish people to Russia. Moscow’s unprovoked invasion of Ukraine’s sovereign territory is therefore viewed with skepticism.

Relations with China could also see some changes. Aksener recently hosted a visit with Omer Kanat, the chairman of the World Uyghur Congress, to discuss how Turkey could help to protect this vulnerable community from persecution. Other opposition leaders have similarly expressed interest in protecting the Uyghur population.

Adding to these areas of cooperation, Turkey plays a key role in providing stability to regional energy security and food security since the country sits at the most important transit point between the Black Sea grain economies and serves as a primary conduit for the energy resources of the Central Asian basin. The pandemic and Russia’s war in Ukraine are evidence that even the slightest disruption in these markets sends shockwaves through the global economy, where shifts in fuel and food prices can result in widespread discontent and even oust governments.

But with closer cooperation, opportunities can multiply. Turkey is close in proximity to more than half the world’s oil and gas reserves, it is well positioned to become a major thoroughfare for energy security and can, potentially, play an important role in the development of eastern Mediterranean natural gas reserves.

The current government has wasted numerous opportunities to develop a more prominent role for Turkey in the region because it has been too focused on appearance over substance, populist slogans over well-thought-out policies, and petty gamesmanship over substantive statecraft. If Turkey actually wants to have “zero problems with neighbors” then it needs a government that will treat neighbors in good faith, not seek to exploit circumstances for domestic political gains and against the interests of its own people.

In their platform, Aksener and the IYI Party have recognized the importance of restoring what used to be a highly functional set of multilateral relationships with Turkey’s allies. This does not mean that all differences and disagreements would dissolve overnight, but it does mean that opportunities for cooperation would expand significantly, contributing to the stability and prosperity of Turkey, the region, and beyond.

For these reasons, this election is one to watch closely. It may be the final opportunity for Turkey’s voters to seek true representation in their leadership.

Prof. Ivan Sascha Sheehan is the associate dean of the College of Public Affairs and past executive director of the School of Public and International Affairs at the University of Baltimore. Opinions expressed are his own. Follow him on Twitter @ProfSheehan.

Image: Shutterstock.