Forgotten Failure in Bosnia

Despite a once celebrated NATO intervention in the Balkans, the region is still a mess.

Twenty years ago this August, there was no hotter story in the emerging global media than Bosnia and its terrible civil war, which was unfolding gorily in near real time. CNN in particular made great copy on the conflict, and worldwide its emerging star Christiane Amanpour became an icon with her “live from Sarajevo” pitch.

Twenty years ago this August, there was no hotter story in the emerging global media than Bosnia and its terrible civil war, which was unfolding gorily in near real time. CNN in particular made great copy on the conflict, and worldwide its emerging star Christiane Amanpour became an icon with her “live from Sarajevo” pitch.

Just how accurate much of the reportage out of bloody Bosnia was that fateful summer remains an open question. The war’s position as the first extended conflict to take place in the context of 24/7 global TV coverage before the rise of Internet fact-checking seems historically important. Yet there can be no doubt that “advocacy journalism” did a magnificent job at forcing Western governments to pay attention and eventually intervene militarily in Bosnia.

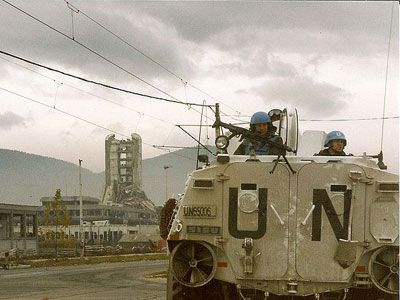

Even the masterful politico Bill Clinton, who initially professed minimal interest in foreign affairs, least of all Balkan conflicts which few Americans understood, wound up pushed by the media and advocates to get involved in Bosnia’s fratricide. Soon, it became America’s and NATO’s problem. By the autumn of 1995, the United States was brokering a deal to end the fighting, the so-called Dayton Accords, and almost sixty thousand NATO troops soon headed to Bosnia to keep a then-fragile peace.

What a difference two decades makes. Bosnia remained front-page news around the world through much of the 1990s, particularly with spikes like the July 1995 Srebrenica massacre and subsequent NATO military intervention in the conflict. But by the end of that decade, CNN and others had moved on to other trouble spots: Kosovo, Sudan, East Timor, eventually Iraq and Afghanistan. Today, Bosnia rarely generates news coverage in the West, much less on the front page. As a result, most foreigners have little sense of how dismally failed a state Bosnia and Herzegovina actually is in 2012.

Matthew Parrish, an attorney who played a part in helping to rebuild the shattered country, has just published an article detailing Bosnia’s “ragged demise”—a piece which is as depressing as it is accurate. The always-weak Bosnian edifice built at Dayton is on the edge of complete collapse under the weight of its own dysfunctions, local corruption and politicking, and Western indifference. As a legion of critics has pointed out since the ink was still moist in Ohio, Dayton paved paths for trouble by enshrining two substate entities—the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina and the Republika Srpska—under a weak, more or less notional, Sarajevo leadership, which has been ruled in quasi-colonial style under a European-appointed high representative since the war’s end.

The federation was from the start an unhappy marriage of Bosnian Muslims (Bosniaks) and Croats; the latter were ambivalent about being joined to the Bosniaks, whom they fought a nasty war against in 1993–1994 (one of the underreported aspects of the conflict since it did not easily fit the CNN version of events). Now most Croats, who feel they were shanghaied into this arrangement by the Americans and NATO, want out of the federation, where they are dominated by the majority and therefore politically superior Muslim population. Yet the Dayton structure allows no such modifications, and Bosniak-run Sarajevo would resist any changes mightily.

Similarly, the mere existence of the Republika Srpska, seen as a national home by Bosnia’s Serbs, is regarded at best as an affront by Bosniaks, at worst as “a reward for genocide.” In such a rhetorical climate, it’s hardly surprising that the two entities have moved further apart since the guns fell silent in late 1995, and the Serb leadership in the capital of Banja Luka continues to do its level best to obstruct any Bosniak moves to create a functional state-level apparatus run out of Sarajevo. While Muslims see the Republika Srpska as a temporary measure, for Serbs it is the bare-minimum requirement for their remaining in any sort of Bosnian state, however marginally. Independence is spoken of openly in Banja Luka as an option, though NATO and the EU have made clear that is not on the table, while not clarifying why Kosovo can be separated from Serbia but the Republika Srpska must not under any circumstances leave Bosnia.

Dayton and its colonial overlords can claim some successes. The warring factions have been disarmed and disbanded, having united gradually in a Bosnian military which is small and underfunded and no threat to anyone. A return to fighting in 1990s fashion is impossible now, since there simply are not enough weapons in the country, especially heavy weapons, to sustain a serious war. In that limited sense, NATO can claim success, though one wonders whether such a limited goal could have been achieved at lower cost than was required, particularly the maintenance of tens of thousands of NATO troops—about a third of them U.S. forces—in the country through 2004, when the mission was handed over to EU peacekeepers.

In every other area, however, Dayton-created Bosnia has been a failure, and in some ways a dismal one. Promised interethnic reconciliation never got off the ground, and enmity among Serbs, Croats and Muslims is as deep now as twenty years ago, as nationalist views have been passed on to the next generation. Hopes that wartime refugees—something like half the population—would return to their prewar homes never panned out on any scale. This disappointment came despite massive efforts by NATO, the EU and NGOs, who were slow to accept the war’s clear lesson: most Bosnians do not want to live among people not of their ethno-religious group.

Above all, Dayton’s promise to rebuild some sort of functioning civil society and economy in Bosnia has been a huge disappointment. While late Communist Bosnia was troubled by all the same challenges of governance and economics found across Eastern Europe at the time, the flawed conditions of 1990 seem like paradise compared to the swamp of crime, corruption and poverty to which Bosnia has become under Western leadership. Official unemployment stands around 50 percent, but that may be too optimistic, while post-Dayton Western investments in the country have dried up in the face of intractable corruption and theft. Smart estimates state that at least one-fifth of the billions of dollars in Western aid after 1995 was simply stolen, off the top, by politicos and mafiosi, who are often the same people.

While the black and grey sectors are thriving, just as they did during the war, the legal economy can be said to hardly exist at all, beyond Western handouts which have been evaporating in recent years as attentions have dwindled and bigger wars have taken aid money away from the Balkans. The human toll of “peace” in Bosnia, in what a generation ago was a reasonably developed and prosperous European country, is difficult to express.

There is ample blame on all sides to go around, and the Bosnians themselves must bear a major portion of the responsibility for the crime, corruption and thievery that rule lives and institutions. Yet it is the elites in all entities who benefit from the institutionalized criminality, while average Bosnians suffer daily amidst poverty and exclusion, all under nominal Western leadership.

And nominal it is, as the EU’s high representative has essentially ceased to function. What America, NATO and the EU have wrought in Bosnia presents a cautionary tale, particularly for the many commentators who hail Bosnia as a rare win in the Western intervention column. At root, Dayton imposed a neocolonial model without neocolonial benefits. While NATO and the EU took it upon themselves to run the broken country, nominally and in a sometimes arbitrary fashion, this leadership made little difference, as local politicos stayed in place.

The example of Bosnia raises awkward questions about the efficacy of Western “nation building” in broken societies, even relatively small and developed ones which should be easy to fix compared with much bigger and more damaged places like Iraq and Afghanistan. Average Bosnians saw little change, and little reform, but a lot of aid money—which in most cases enriched corrupt elites without helping the population very much. Dayton, behind an illusion of change, empowered the criminal cadres that led Bosnia into a terrible war while doing little for the victims of that war and doing even less to reform a very damaged and sick society.

Today, Bosnia and Herzegovina—Dayton’s ramshackle, quasi-colonial creation—is approaching a complete collapse, as political paralysis mounts and economic woes worse. The Bosnians cannot save themselves, and the saviors of the 1990s seem uninterested. Will anyone in the West, distracted by wars and crises unimaginable when NATO intervened in Bosnia in 1995, take notice?

John R. Schindler is professor of national-security affairs at the U.S. Naval War College and a former intelligence analyst and counterintelligence officer with the National Security Agency. He has written widely on Balkan affairs and blogs at The XX Committee. The opinions expressed here are entirely his own.