America Must Dissuade China's Interest In Nuclear Arms

These steps should assure America's allies and make real nuclear threat reductions, including useful arms limits, much more likely not just in East Asia, but globally.

Washington’s security gurus like to say that America’s nuclear arsenal soothes its allies while dissuading them from scratching nuclear weapons itches of their own. Critics may contest the maxim, but in East Asia, an opposite contention—that China’s growing nuclear proficiency is dangerous—is gaining ground. In fact, China’s nuclear ambitions not only increasingly threaten the United States, but could push America’s key Asian allies—Japan and South Korea—out of Washington’s security orbit into acquiring nuclear weapons of their own.

How likely is it that China’s stockpile will grow? It is highly likely. The only question is how fast and by how much. Currently, the Defense Intelligence Agency estimates China’s nuclear arsenal to be in the “low couple of hundreds” and projects it will double by 2030.

Compounding this trend are the “peaceful” nuclear programs that China is pursuing. These could allow China to ramp up its nuclear weapons production significantly. First, Beijing has and is building far more uranium enrichment capacity than its civilian nuclear sector needs. Experts project China’s uranium enrichment capacity might soon supply all of its civilian requirements and still fuel one thousand or more nuclear weapons a year. Second, China is ramping up its fast reactor and plutonium recycling programs. In a decade or less it could be producing many hundreds of weapons’ worth of plutonium a year.

China is also diversifying, growing, and enhancing the platforms that might deliver its nuclear arsenal. It is not just developing more precise missiles of various ranges, but also building stealthy, long-range bombers and will soon put to sea more advanced submarines armed with modern submarine-launched ballistic missiles. What’s more, hypersonic, multiple-warheaded, maneuvering, and low-flying missiles capable of besting the United States and allied missile defenses may all contribute to China’s nuclear threat in the coming decade.

All of this portends a China that in one to two decades could sprint to nuclear parity with either the United States or Russia.

What difference might this make? Plenty. China’s nuclear use doctrine already is undergoing review. For decades China’s military claimed it would only use its small, crude nuclear arsenal to respond to a nuclear attack. More recently, though, Chinese security experts have toyed with scenarios under which China might use nuclear weapons first. As Beijing acquires more and more lethal nuclear weapons systems, there will be a growing disconnect between its nuclear use doctrine and the force it actually fields. Others will be left to conclude that China’s actual approach to nuclear use is far more offensive than it lets on.

This is worrisome enough but there’s more: As China builds up its nuclear capabilities, America’s allies will slowly freak out. Most people don’t know it, but Japan and South Korea have both given more than passing consideration to nuclear weapons. South Korea actually had a covert program in the 1970s to acquire them. It currently is hankering to enrich uranium for a nuclear submarine program and wants to recycle plutonium for a fast reactor it hopes to build and operate sometime in the late 2020s.

Japan has also harbored ambitions of developing a large fast reactor (as one former Japanese defense minister explained as a “tacit deterrent”). It has stockpiled nearly 2,500 bombs worth of nuclear explosive plutonium on its soil in anticipation of fueling this system. There are only two problems: Japan no longer has a serious fast reactor program and Tokyo is planning on opening a large spent fuel reprocessing plant at Rokkasho that would add roughly 1,500 weapons worth of explosive plutonium a year on top of its current domestic stash of ten or more tons.

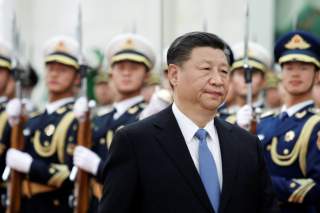

This then raises the question of what, if anything, the United States and its allies should do. First, discourage all sides from piling up more nuclear kindling. President Donald Trump should explain to Chinese leader Xi that, neither Beijing nor Washington should encourage Japan or South Korea to go nuclear. Instead, both should reassure Tokyo and Seoul that they don’t need nuclear weapons and that neither they, nor China, nor any other country should be hedging their security bets with unnecessary, uneconomic, enrichment and reprocessing programs.

Second, Washington needs to make clear that China’s efforts to build up its nuclear-capable missile force will come at a military and diplomatic cost, one that should actually make agreeing to limit them more attractive. This could take time. America may currently lack the military and missile clout it needs to cut a sound regional missile deal in Asia. But Washington should make it clear to Beijing that this will change—relatively quickly—and that engaging in fair negotiations on this front now is ultimately in China’s interest.

Finally, and related, America’s military modernization efforts should be designed to diminish the value of nuclear arms. In particular, investing in advanced conventional capabilities in which America has a comparative advantage—including space systems, precision weaponry, and submersible technologies—should encourage the PRC to invest in nonnuclear naval, air, and missile systems that are defensive rather than offensive.

One could do more. But taken together, these steps should assure America’s allies and make real nuclear threat reductions, including useful arms limits, much more likely not just in East Asia, but globally.

Michael Mazza is a visiting fellow at the American Enterprise Institute (AEI) and senior non-resident fellow at the Global Taiwan Institute.

Henry Sokolski is executive director of the Nonproliferation Policy Education Center in Arlington, Virigina and author of Best of Intentions: Our Not So Peaceful Nuclear Future (Second edition, 2019).

Image: Reuters