America's History of Protectionism

Protectionism has been a frequent feature of the republic since its founding.

A CENTURY of back-and-forth over trade highlighted the country’s inherent political divide on economic philosophy, with sentiment roughly even. But the issue may not have been as significant as both sides believed. Washington Sen. John B. Allen argued during the McKinley-tariff debate that many other factors besides trade policy contributed to America’s economic growth. The country’s history, he said, showed that “prosperity and adversity have come alternately under both a high and a low tariff.”

Allen had a point. The United States was a young and lively nation, rich in resources and geographical advantages, populated by a vibrant and expansionist people, powerfully positioned upon the American continent, facing two oceans. Its destiny seemed secure irrespective of fiscal policies at any given time or the political passions unleashed by the tariff issue. In any event, the Wilsonian approach prevailed through most of the 1920s.

Then came the Smoot-Hawley Tariff of 1930, which raised duties on some twenty thousand imported goods, in some instances to record levels. American economists had petitioned the president to veto the bill as economic poison. “Countries cannot permanently buy from us unless they are permitted to sell to us,” said the economists, echoing the views of that rustic Texan, Roger Mills, “and the more we restrict the importation of goods from them by means of even higher tariffs the more we reduce the possibility of our exporting to them.” The country was in the early stages of the Great Depression, and as its ravages upon the American people increased, the Republicans’ political standing plummeted. In the 1930 midterm elections, opposition Democrats took control of the House of Representatives with a gain of fifty-two seats. Two years later, with Franklin D. Roosevelt on the presidential ballot, the Democrats gained another ninety-seven House seats and twelve in the Senate. They came within a single seat of capturing the Senate. Hoover, on the ballot for reelection, didn’t crack 40 percent of the popular vote.

With Democrats now enjoying a commanding position in American politics, tariff rates began a steady decline that would last for decades. The free-trade consensus became clear. The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) was established in 1947 to reduce trade barriers and promote unfettered trade among capitalist nations. In 1995, that organization became the World Trade Organization. This ideology of open markets and low tariffs dominated worldwide following the fall of Communism.

But that was after the 1970s and 1980s, when hard times for domestic manufacturers generated protectionist calls from beleaguered industries and organized labor. A synthesis of sorts emerged after Detroit automakers and the United Auto Workers jointly sought protection from Japanese imports. Reagan rejected high tariffs in favor of voluntary restrictions based on quotas arrived at through diplomatic agreements (not unlike McKinley’s reciprocity concept). But this led Japanese automakers to import larger, more expensive cars into the United States, thus getting into the more lucrative upper end of the car market. Eventually, Japanese automakers moved their factories to U.S. soil, thus manufacturing their cars with American labor to leaven protectionist pressures.

Meanwhile, the impetus for free-trade agreements grew, leading to Reagan’s Canada-U.S. Free Trade Agreement of 1987 and to President Bill Clinton’s far more momentous North American Free Trade Agreement of 1994, called NAFTA. This far-reaching legislation brought together a coalition that included a center-left Democratic president bent on “triangulating” major issues to capture a wide swath of moderate voters, a GOP dedicated to reducing barriers to commerce wherever they could be found and a U.S. electoral majority. Only organized labor seemed to be the odd man out. Free trade had never been so thoroughly entrenched in American politics.

But developments were percolating in American society that would render this consensus temporary, as indeed every political consensus is. The man who perhaps best personified these developments was conservative commentator and gadfly presidential candidate Patrick J. Buchanan. As a lifelong conservative and zealous supporter of Reagan, whom he served as communications director from 1985 to 1987, Buchanan thoroughly embraced the free-trade outlook. Indeed, when presidential speechwriter Ben Elliott wrote that rousing free-trade address that was deep-sixed by White House Chief of Staff Donald Regan in the fall of 1985, Pat Buchanan was his boss—and cheered him on as he drafted the speech.

But after leaving the White House, the pugilistic conservative experienced a conversion when he visited an uncle in Pennsylvania’s Monongahela Valley, prosperous iron and steel territory for decades before falling on hard times. “Why are you supporting this free trade?” asked the uncle. “Don’t you know what’s happening to the Mon Valley?” Buchanan looked around and saw that his uncle was right when he said, “The Mon Valley is dying.” Imports were killing it. “The more I read of local businesses and factories shutting down, workers being laid off, towns dying as imports soared,” wrote Buchanan later, “the more I began to ask myself, The price of free trade is painful, real, lasting—where is the benefit other than the vast cornucopia of consumer goods at Tysons Corner?”

In his presidential bids and writings, Buchanan became the champion of those working-class Americans caught in this tightening vise. He soon discovered that he was “trampling on holy ground,” as he put it, adding: “For some conservatives, to question free-trade dogma is heresy punishable by excommunication.” But he wondered why conservatives should despise protectionism when protectionism had been the policy of their Republican Party for nearly seventy years after 1860—and of its forerunner parties, the Whigs and Federalists, for sixty years before that. Protectionism was part of the party’s heritage, he concluded, and now the plight of the country’s working class required a return to that heritage. His focus would be those working families of America ravaged by the obliteration or decline of the country’s manufacturing base.

THAT IS the focus also of Donald Trump, whose rhetoric on trade sounds as if it were pulled straight from Buchanan’s book on the subject, The Great Betrayal. Trump’s political success thus far, and its fallout here and abroad, reflect the reality that we are moving into a new era on trade. Trump’s free-trade attacks, like Buchanan’s, jibe with his attacks on globalism, open borders, humanitarian interventionism in foreign policy—and the American elites who have fostered these policies.

This new mood is a death knell for the proposed twelve-nation Trans-Pacific Partnership, designed to usher in a new generation of free-trade deals. Even the Democrats’ presidential candidate, Hillary Clinton, now opposes this initiative, which she once hailed as “the gold standard” in such policy concepts. It was also thoroughly in line with her husband’s free-trade philosophy. Now she sees the handwriting on deteriorating factory walls.

This is not the 1980s, when presidential aide Ed Rollins could create a tempest in a teapot over trade policy in a free-trade administration struggling merely to tamp down pressures for protectionist measures in a fundamentally free-trade era. This is more like the 1790s, 1820s, 1890s and 1920s, when protectionism played a major role in U.S. policymaking. Hamilton, Clay, Lincoln, McKinley and Hoover are back.

Robert W. Merry is a contributing editor at the National Interest and an author of books on American history and foreign policy.

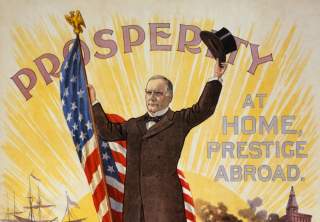

Image: 1896 William McKinley campaign poster. Wikimedia Commons/Public domain