China Concerns: Why the GOP Sees Beijing as Shifting from Friend to Foe

For more than four decades, most Republicans were enthusiastic supporters of engagement with China. Now, they almost unanimously embrace the “China threat” narrative.

Ever since Richard Nixon and Mao Zedong rekindled the U.S.-China relationship in 1972, Republicans have generally perceived China policy as a balancing act between three key constituencies: the business community, the national security community, and the party’s conservative wing. The GOP’s vital center favored engagement with China in the 1970s as a means of countering Soviet power, and it was adamantly pro-commerce beginning in the 1980s.

There were always exceptions, of course. Congress often applied the brakes when the president sought closer China ties, and one could always find conservatives willing to stand up for Taiwan or Chinese Christians. Even many pro-business moderates remained wary of Beijing, especially during periods of bilateral crisis. Nevertheless, between the Reagan and Obama presidencies, most Republicans firmly backed the expansion of Sino-U.S. economic ties.

Not so today. In stark contrast to the Republican Party’s erstwhile role as cheerleader for globalization, free trade, and China’s integration into the world order, the GOP now carries the torch as America’s tough-on-China party. Today’s Republicans almost unanimously combine concerns over national security, commerce, tech, intellectual property, and even human rights into a grand “China threat” narrative.

What happened? On the security front, a richer, more powerful China began to look like a more threatening China, especially after 2008. Defense hawks point to Beijing’s military buildup, its bold regional posture, its island-building campaign, and its pursuit of advanced technologies, all of which fuel the perception that China seeks to be the preeminent Pacific power. On the commercial front, foreign businesses facing technology-transfer requirements and market access restrictions are no longer so sanguine about the China market. Alongside long-standing American business concerns such as IP theft and currency manipulation, many now fear losing global market share to new Chinese ventures.

This partisan shift goes far beyond the Trump administration and its trade war. Even a cursory glance at recent congressional activity shows that Republicans spearhead most China-related bills and committee hearings. Among the most vocal senators are Marco Rubio (R-Fla.), Jim Talent (R-Mo.), Jim Inhofe (R-OK), Ted Cruz (R-TX), Cory Gardner (R-CO), Tom Cotton (R-AR), and Josh Hawley (R-Mo.), along with their House counterparts Christopher Smith (R-NJ), Ted Yoho (Florida), Will Hurd (R-TX), and Steve Chabot (R-OH). These GOP legislators have sponsored dozens of China-relevant bills in 2019 alone, including ones calling for the reaffirmation of U.S.-Taiwan relations, sanctions on Chinese commercial entities, and religious liberty.

Cotton, Hawley, and Gardner stand out as members of the younger generation of legislators. Having come of age in the era of rising China, they seem to have fewer illusions about Chinese power and fewer pressures to defend an outmoded status quo. Hawley recently called China “the most significant threat of the twenty-first century,” while Cotton waxed Reaganesque in accusing Beijing of building a “new evil empire” based on repressive measures and mass surveillance.

Rubio, who has emerged as the unofficial leader of this GOP cadre, has invoked “China threat” rhetoric early and often. As he said at a Senate intelligence hearing last year, “I’m not sure in the 240-something-odd-year history of this nation we have ever faced a competitor and potential adversary of this scale, scope and capacity.” In 2018–19 alone, Rubio has sponsored bills to sanction Beijing for its maritime activities, to prevent small business assistance from going to China, to promote fair trade, and to counter Chinese influence operations.

Perhaps the most significant turnabout is among the party’s pro-business wing. In years past, Beijing could count on two things: American corporations would lobby in Washington on China’s behalf, and business-oriented Republicans would support U.S.-China economic integration. When Congress annually debated most-favored-nation (MFN) trading status for China in the 1990s, major corporations joined with mainstream Republicans to support MFN renewal. After the Clinton administration inked a bilateral WTO accession agreement with China in 1999, business interests sought to grant China permanent normal trade relations status (PNTR), while labor- and human-rights advocates sought to withhold such status in order to maintain leverage against China.

Since Republicans were in the vanguard of the free trade movement, they were also at the forefront of the pro-PNTR fight. Long-serving Iowa Senator Chuck Grassley embraced the commercial liberal zeitgeist, arguing in 2000, “History shows that when countries trade with each other on a nondiscriminatory basis, everyone wins. . . . We cannot have an effective, open-world trade system that excludes China.” PNTR passed both houses with strong GOP support—74 percent of House Republicans favored it against only 34.6 percent of House Democrats—and President Bill Clinton signed it into law in October 2000.

Oh, what a difference two decades makes. Today’s Republicans have not quite abandoned free trade, but they are willing to accept a trade war because their party loyalty and electoral ambitions parallel their animus toward a richer, stronger China. As Sen. Chuck Grassley (R-IA) recently argued (sounding far less optimistic than he did in 2000), “China simply has not lived up to the commitments it made when it joined the WTO. . . . [and] WTO rules have not effectively constrained China’s mercantilist policies and their distortion of global markets.” There may be grumbling over the trade war, especially in the Farm Belt, but otherwise, there are no signs of a Republican revolt.

The numbers fueling this turnabout are familiar. China has averaged a staggering 9.49 percent annual GDP growth since 1989, while in the same period the Sino-U.S. trade deficit has ballooned from $6.2 billion to $419.5 billion. Subsequent to China’s 2001 WTO accession, the United States shed around five million manufacturing jobs, and some scholars and think tanks still insist that China trade is more of a culprit than automation. And although U.S. exports to China rose consistently beginning in the 1980s, they have plateaued since 2013. Meanwhile, U.S. government reports on China’s trade behavior have grown ever more damning. The U.S. Trade Representative’s 2018 and 2019 releases on China’s WTO compliance concluded that the United States had erred in supporting China’s WTO entry on insufficient terms.

All of these factors make it more politically acceptable for Republicans to portray themselves as “tough on China.” And now that Beijing has clarified its intention to make the nation a leader in advanced technologies, foreign companies that fear future displacement are no longer so willing to lobby for China. As recently as 2015, American business leaders were telling Gardner that China needed more time to implement reforms. “I don’t hear the same thing from American businesses today,” Gardner noted more recently. “What I hear now is that the U.S. needs to act on the predatory economics.”

As for the current Republican presidential administration, the “China threat” narrative runs through stacks of executive reports on security, trade, and technology. Typical is the 2018 National Defense Strategy, which called China “a strategic competitor” that is “leveraging military modernization, influence operations, and predatory economics to coerce neighboring countries to reorder the Indo-Pacific region to their advantage.”

While much has been made of the trade war and the consultative roles of such China hawks as White House trade adviser Peter Navarro, former White House adviser Steve Bannon, and Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, Vice President Mike Pence has quietly emerged as the administration’s hatchet man on China. In what is otherwise a highly transactional presidency, Pence has carried the standard for the party’s conservative wing by addressing moral and political values in China and elsewhere. Last October, he unleashed a wide-ranging indictment of Beijing’s actions in trade, tech, influence operations, and human rights, effectively arguing that the West was fooled into supporting China’s global engagement. “Previous administrations made this choice in the hope that freedom in China would expand in all of its forms,” he argued, “but that hope has gone unfulfilled.” He has returned to this theme in recent months.

Today’s Democrats are hardly pro-Beijing, but they are certainly much less zealous than their GOP counterparts. A few have joined the counter-China chorus, including Sen. Bob Menendez (D-NJ), Sen. Chris Coons (D-Del.), and Rep. Gerry Connolly (D-Va.), but so far China has been a sideline topic in the Democratic presidential debates, and the candidates have yet to expound a vision that differs significantly from President Donald Trump’s vision. These days, even The Atlantic and The Nation marvel at Democrats’ downplaying of China issues. For the time being, at least, the new anti-China lobby is firmly entrenched on the right side of the aisle.

Dr. Joe Renouard teaches at the Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS) in Nanjing, China. His most recent book is Human Rights in American Foreign Policy: From the 1960s to the Soviet Collapse (Penn Press). He has also contributed essays to The Los Angeles Times, the National Interest, American Diplomacy, The Diplomat, HNN, and several edited collections.

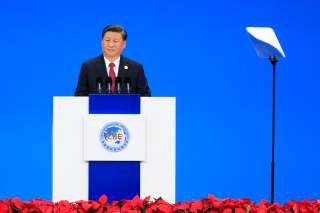

Image: Reuters