China in the Middle East: An Irresponsible Power?

China has been actively seeking economic, political, and strategic opportunities in the Middle East without acting as a responsible great power in the Middle East. China focuses on building economic ties with Middle Eastern countries but avoids taking risks or getting involved in regional conflicts. This approach raises doubts about its credibility as a responsible global power and may damage its reputation in the long term.

In recent years, China has aimed to embrace the mantle of a responsible global player. With its substantial stake in the established international order and its status as a large and increasingly influential nation, China recognizes its unique obligation to sustain the global system and contribute to worldwide endeavors to tackle pressing issues. To this end, China has made significant efforts, such as actively engaging in international peacekeeping missions, cooperating with other nations to address climate change, and assisting in the fight against the COVID-19 pandemic. However, despite these endeavors, the practical implementation of responsible global leadership is fraught with significant obstacles, and various challenges and setbacks have marked China’s journey.

Recent events in the Middle East have raised questions about China’s role in the region. Rather than acting like the responsible great power it purports to be, it has not taken any concrete action to address the ongoing crises. It has neither condemned Hamas’s attack on Israeli civilians on October 7, 2023 nor condemned Houthi attacks on Red Sea shipping. It also did not join the U.S.-led coalition, Operation Prosperity Guardian, which defends shipping in the Red Sea. China has not put forward any diplomatic initiatives to tackle any aspect of the ongoing and interconnected crises in the region, apart from expressing a general preference for convening a peace conference.

Meanwhile, the United States has demonstrated its role as a responsible global power by affirming its commitment to upholding regional security and stability, notably through safeguarding trade routes and deterring Iran and its regional proxies. In contrast, China has not publicly presented a viable alternative to Washington’s actions and appears content to critique the U.S.’ involvement and response to the crises. China’s actions and inaction underscore that, despite decades of projecting an image of responsibility and cooperation in Middle Eastern affairs, it continues to pursue a notably self-interested approach characterized by free-riding and opportunism in the region.

In recent decades, China has sought to quietly consolidate relations in the Middle East without being trapped in deadly regional antagonisms. It pursues this objective primarily by focusing on political and economic ties while steering away from crises. However, it has often appeared either unable or unwilling to act diplomatically, militarily, or economically as a responsible great power to maintain regional security and contribute to international efforts to address Middle East challenges.

Beijing garnered considerable acclaim for facilitating a reconciliation deal between Saudi Arabia and Iran in March 2023. The move showcased Beijing’s emerging diplomatic skill and proactive approach to mitigating tensions in one of the world’s most volatile regions. China’s role as a mediator in this agreement marked a departure from the traditional dominance of U.S. influence in the Middle East. Chinese diplomats hailed it as a milestone towards achieving peace and stability in the region, emphasizing the importance of dialogue and consultation in resolving international disputes. They pledged to sustain China’s constructive engagement in the area going forward. However, it is crucial to acknowledge that while China’s involvement was significant (it assisted the diplomatic process, but the momentum fundamentally came from within the region), it carried minimal risk. This allowed Beijing to capitalize on the opportunity presented by the Saudi-Iranian reconciliation without facing substantial drawbacks. In essence, China leveraged the situation to its advantage, benefiting from a scenario with little potential downside.

Over the past decade, China has notably expanded its economic, political, and, to a lesser degree, security presence in the Middle East, emerging as the primary trade partner and external investor for numerous countries within the region. Traditionally, this region held limited importance in Chinese foreign policy. However, China’s rapid rise as a global power has prompted a shift in its strategic priorities, extending its ambitions towards the West. China now holds substantial and strategic interests in the Middle East, mainly due to the presence of six of its top ten oil suppliers in the region. With oil playing a crucial role in China’s economic development, the region’s importance has surged accordingly.

The region also plays a crucial role in China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), a massive endeavor to invest hundreds of billions of dollars in connecting infrastructure and facilitating trade across Central Asia, South Asia, Africa, and Europe. As a pivotal part of this plan, the Middle East is an essential global commerce trade hub and transit point. Consequently, China’s interests in the region extend beyond ensuring a secure and uninterrupted oil flow. They also encompass maintaining geopolitical stability to facilitate the advancement of its development projects, both on land and at sea.

While the United States remains the dominant extra-regional great power as the turmoil in the Middle East threatens to spread more broadly, China’s growing presence across the region raises an important question: Does Beijing exhibit responsible behavior as a great power in this region? China has positioned itself at an indisputable advantage in the Global South—including the Middle East—compared to the United States and the EU through the BRI and other bilateral and multilateral initiatives. China aims to reshape the world economic order through the BRI, promote development via the Global Development Initiative (GDI), exert geopolitical influence through the Global Security Initiative (GSI), and introduce ideational changes via the Global Civilization Initiative (GCI). These initiatives synergize and form part of China’s “indivisible security concept.” These initiatives are further complemented by the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO, which is expanding slowly) and BRICS+ (the traditional BRICS countries plus Brazil, Ethiopia, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE). Through these initiatives (the BRI, GSI, GCI, GDI, SCO, and BRICS+), Beijing is slowly reconfiguring the international geography and reshaping the world order by offering its own “narratives of global order and reordering.”

Nevertheless, escalating conflict in the Middle East and increased U.S. involvement in regional affairs present challenges to fulfilling China’s global initiatives. In the broader context, the rise in violence does not align with China’s interests in safeguarding its investments and bolstering its global reputation. For instance, the attacks by Houthi rebels on shipping in the Red Sea have adversely affected Chinese commercial interests and have begun to strangle the economies of some of its regional partners. Reports suggest that approximately 90 percent of container ships that typically traverse the southern Red Sea have diverted their routes to avoid the area. This disruption significantly impacts global trade, as Red Sea routes typically handle around a third of all container traffic worldwide and 40 percent of trade between Asia and Europe. The resulting shipping bottleneck has led to a threefold to fourfold increase in container prices, forced energy shipments bound for Europe to circumnavigate Africa, and caused severe disruptions to supply chains due to delivery delays.

China, being not only a major trading nation but also a maritime one, is directly affected by frictions in global trade and is witnessing a trend towards “nearshoring”—the relocation of supply chain dependencies to nearby, more reliable nations to mitigate future disruptions. Furthermore, these disruptions threaten Chinese investments in the Middle East. In recent years, Chinese companies have significantly increased their investments in crucial infrastructure along the East Africa, Suez Canal, and on both sides of the Red Sea.

The breakdown in Red Sea shipping jeopardizes the viability of these investments. As the world’s largest exporter and heavily reliant on oil imports, China is understandably concerned about the potential collapse of shipping lanes in the Red Sea. About half of its imported oil comes from the Middle East, and the Red Sea provides critical access to Europe, one of China’s largest export markets. Even with the Houthis giving a pass to ships flying the Chinese flag, the country’s shipping and exporters are being squeezed by the commercial disruption.

China wants a peaceful and stable Middle East due to the substantial economic losses it would incur from ongoing conflict, particularly in disrupted petroleum supplies and international shipping routes. However, Beijing faces significant challenges in translating this desire into concrete actions for two main reasons: a lack of significant influence and a strong aversion to risk. In many respects, Beijing lacks the level of responsibility expected of a great power in the Middle East and other regions beyond its Asia-Pacific sphere. China’s risk aversion stems from its fear of failure and concerns about potential global overreach. These factors collectively hinder Beijing’s ability to effectively address and mitigate conflicts in the Middle East and elsewhere.

Despite China’s undeniable economic prowess on the global stage, its diplomatic and military influence remains comparatively limited. While China’s military strength is steadily growing, its ability to project power diplomatically and militarily in the Middle East is significantly less pronounced than that of the United States. China’s military capabilities, although advancing, still lag behind its strategic competitor, particularly in terms of projecting air and land power beyond the western Pacific. China’s three commissioned aircraft carriers have yet to venture beyond this region, limiting their ability to exert significant influence in the Middle East. Chinese marines stationed in Djibouti, near the Red Sea, have yet to be deployed beyond participating in counter-piracy operations in the Gulf of Aden.

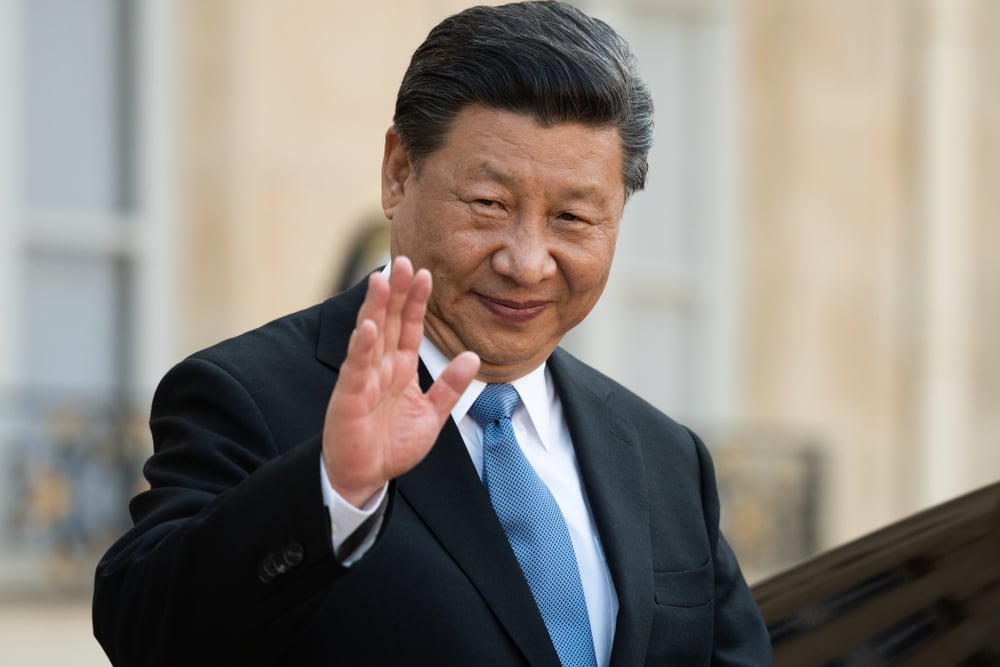

Furthermore, China’s diplomatic influence in the Middle East has been constrained by its primarily economic-focused approach and a reluctance to engage in broader diplomatic endeavors. Unlike other external powers, China has prioritized maintaining positive relations with all Middle Eastern countries. More impartially, Beijing also looks to position itself as the champion of the Global South and present a more attractive and alternative vision to the U.S.-led world order. By distancing itself from U.S. and European rhetoric and initiatives, Beijing aims to differentiate itself as an authentically non-Western voice. President Xi Jinping has promised to “contribute Chinese wisdom to promoting peace and tranquility in the Middle East” and has unveiled a raft of corresponding security and development initiatives in recent years. In reality, however, China’s actions and initiatives in the Middle East are driven partly by a desire to challenge U.S. power.

China’s response to the turmoil in the Middle East illustrates a familiar pattern: prioritizing its interests and reaping benefits while avoiding direct involvement and the associated reputational risks. Its approach involves nurturing political and economic ties while avoiding crises, intervening only when its economic interests are significantly jeopardized and when diplomatic success seems achievable in a short timeframe. This behavior stems from geopolitical, economic, and military considerations. However, it raises questions about China’s adherence to the principle of “with great power comes great responsibility.” Middle Eastern countries may rightfully criticize China for its opportunistic approach and urge it to shoulder some responsibility for securing trade routes and resolving conflicts in the region, actions that would also serve China’s interests. In the long run, China’s reputation may suffer if it continues to appear as a non-responsible global power and an opportunistic bystander in the Middle East, failing to engage constructively and contribute to regional stability.

Dr. Mordechai Chaziza is a senior lecturer at the Department of Politics and Governance and the Multidisciplinary Studies in Social Science division at Ashkelon Academic College (Israel) and a Research Fellow at the Asian Studies Department, University of Haifa, specializing in Chinese foreign and strategic relations.