China Will 'Pull the Trigger' in the South China Sea

Beijing may want to “win without fighting” as Holmes suggests, but it cannot win without confronting.

The National Interest has recently hosted a debate on whether China wants a confrontation in the South China Sea.

In a January 24 piece, “China Wants Confrontation in the South China Sea,” I argue what the title states. James Holmes, in “No, China Doesn’t Want Confrontation in the South China Sea,” takes a different view.

In this piece, I show China wants more than just to provoke a confrontation in that contested body of water. It wants to “pull the trigger.” Beijing, we should recognize, will almost certainly use force if it gets the opportunity.

That’s more than just a prediction. It is an extrapolation from past Chinese behavior.

“An antagonist who stumbles into the arena of combat is different from one who strides into the arena,” writes Holmes, the first holder of the J. C. Wylie Chair of Maritime Strategy at the Naval War College. In this regard, Jim, whom I greatly admire and respect, is certainly correct.

Recommended: America Has Military Options for North Korea (but They're All Bad)

Recommended: 1,700 Planes Ready for War: Everything You Need To Know About China's Air Force

Recommended: Stealth vs. North Korea’s Air Defenses: Who Wins?

China, however, is more than stumbling into the South China Sea. It is using its power to push out others, namely, the United States, which has no South China Sea sovereignty claims, and rival claimants. Beijing may want to “win without fighting” as Holmes suggests, but it cannot win without confronting.

Confrontation, unfortunately, is “inevitable,” as Yu Maochun of the U.S. Naval Academy points out. Beijing is trying to push out its borders and expand control of peripheral waters. “China’s geopolitical and geostrategic priority is to revise or change the existing international order that has been based upon a complex system of rules, laws, and customs that govern various global commons including the South China Sea,” he told The National Interest. “Revisionism brings unavoidable confrontation.”

Moreover, Anders Corr, also in comments to this publication, notes a crucial asymmetry.

“The key point is that China accepts the risk of escalation to a greater extent than does the U.S., because China uses confrontation to alter the status quo in its favor,” Corr, editor of the just-released Great Powers, Grand Strategies: The New Game in the South China Sea, writes.

James Fanell, once the top intelligence officer of the U.S. Navy’s Pacific Fleet and now a noted commentator on defense matters, is concerned that the Chinese desire confrontation to achieve their “centennial goal of the great rejuvenation” of the Chinese state. This goal, he told The National Interest, “requires the consolidation of all its perceived territories, to include the maritime territories of the South and East China Sea.”

China’s ambition is growing. Beijing is now thinking beyond the “cow’s tongue,” the area defined on its official maps by nine or ten dashes. In December 2016, Chinese vessels seized a U.S. Navy drone in international water, in sight of the USNS Bowditch and in spite of the Bowditch’s radio demands to leave the drone in the water. The site of the seizure, about 50 nautical miles northwest of Subic Bay, was so close to the Philippine shore that it was beyond China’s claim of sovereignty.

This is not to say that, these days, China is always confrontational. As the Naval Academy’s Yu told me, “History has proved time and again that when China feels a confrontation at a particular time under a particular circumstance will not yield a desirable consequence, China does not want to have a confrontation.”

But there are times when circumstances change, when Beijing thinks it can not only confront but also do so with force. “In 1974,” Yu writes, “when the U.S. effectively abandoned its military involvement in Vietnam, the Chinese seized the opportunity and fought a naval battle with the South Vietnamese navy, chased away Vietnamese dwellers, and occupied the Paracel islands. In this sense, China is the consummate opportunist.”

Opportunism rarely looked so ominous. The issue for the Chinese is not if they use force—“to pull the trigger” as Professor Yu puts it—but when they do so. This means peace in the South China Sea requires constant deterrence. “The United States,” he says, “is, by default and not by design, the only country capable of exerting meaningful impact to preserve the status quo.”

“Neither China nor the U.S. wants even a small war in the South China Sea,” Corr writes. “Both countries prefer to keep their naval forces afloat and their sailors alive.”

But hostile Chinese officers, who feel the U.S. is in terminal decline, think they can get what they want. Fanell believes they might move against a U.S. Navy vessel passing through the South China Sea. “The confrontation would be designed to bloody the nose of the U.S. and remind the region that it is now China’s navy and air force that rule the region,” he warns. He thinks Beijing “will actively seek a near-term military confrontation in the South China Sea.”

The Chinese, fueled by their own sense of power, are now arrogant.

And dangerous. For instance, in August 2014 a Chinese J-11 fighter intercepted a U.S. Navy P-8 reconnaissance plane in international airspace 137 miles southeast of Hainan Island, over the South China Sea.

The J-11 flew directly under the P-8 three times, once coming as close as 50 feet. The Chinese plane also crossed the nose of the American craft with its underside toward the P-8, showing, in a menacing gesture, its weapons loadout.

Then the J-11 pilot flew under the P-8 and came alongside, bringing his wingtips within 20 feet of the Navy plane. Finally, the J-11 conducted a barrel roll over the P-8, passing within 45 feet.

The Chinese Ministry of Defense released a statement showing Beijing’s intent to stop the American surveillance flights and blaming the United States for the incident. Moreover, Xu Guangyu, a retired general affiliated with the China Arms Control and Disarmament Association, said the intercept “was a form of admonishment” of the Americans and a “warning.” State media outlets repeated the message in a concerted campaign.

Buzzing incidents over the South China Sea have continued with regularity, with the last known one occurring less than a year ago.

Yes, as Jim Holmes noted in his title, China may not “want” confrontation. Yet whether China desires confrontation should no longer be at issue. Chinese leaders, by their actions, are in fact confronting other states in the South China Sea.

And they are doing so in exceedingly dangerous ways.

Gordon G. Chang is the author of The Coming Collapse of China. Follow him on Twitter @GordonGChang.

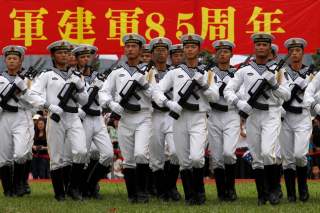

Image: Chinese People's Liberation Army (PLA) navy sailors march during an open day at the Ngong Shuen Chau Naval Base on Hong Kong's Stonecutters Island July 28, 2012. The naval base was open to the public on Saturday, four days ahead of the PLA Army Day on August 1. REUTERS/Tyrone Siu