China's Trade War Isn't Entirely About Trade

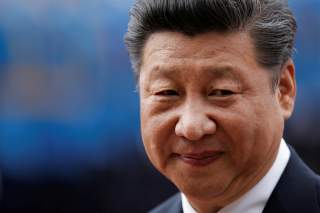

Economic growth remains a critical cornerstone for the Chinese Communist Party and Xi Jinping’s hold over the country.

The United States and China are like two elephants fighting in a field; while they are willing to posture and jostle each other, the ultimate intention is to intimidate, not to destroy. However, what happens between the United States and China has an impact on the global economy. Although a trade deal is likely to be struck between the administrations of Presidents Donald Trump and Xi Jinping at some point during 2019, issues of economic competition and geopolitical rivalry suggest that the current trade war is only one act in a much longer play between two very different systems, one private sector and democratically-oriented, the other geared for state-guided economic development and autocratic.

The flashpoint economic issue between the United States and China is the latter’s long string of large trade surpluses with the former. Despite a year-long trade war between the two countries (complete with tariffs and counter-tariffs), China finished 2018 with a record $419.2 trade goods surplus with the United States (according to the U.S. Census Bureau). Even adding in U.S. service exports, the Chinese surplus in 2018 was a substantial $378.6 billion.

To many Americans (especially those living in the Rust Belt and among trade hawks) the reason for lost manufacturing jobs has been the rise of a China willing to “cheat” by unfair trade practices. These include protecting domestic markets for infant industries; providing cheap credit from state development banks; the forced transfer of technology from U.S. companies operating in China to their local counterparts; and currency manipulation. Although much of the job loss in U.S. manufacturing has been due to automation using technological advances to enhance productivity, the ability to put a face to the culprit has a powerfully emotive effect on U.S. domestic politics.

The loss of jobs in the former manufacturing powerhouses in the United States was certainly a factor in helping Trump win states like Ohio, Michigan, and Wisconsin. His call to “Make America Great Again,” backed by protectionist trade views clearly struck a responsive chord. During the 2016 presidential campaign, then-candidate Trump stated: “We can’t continue to allow China to rape our country, and that’s what they’re doing.”

U.S. companies have indeed faced an uneven playing field with many of their Chinese counterparts. Considerable public sentiment exists that the Trump administration’s tough approach toward China is merited. Related to that is China’s plan to become the world’s dominant technological power (the “Made in China 2025” plan) because it highlights the role of Chinese technology companies in everything (including 5G, space exploration and human surveillance) as an extension of state policy.

Part of Washington’s pushback was the arrest of tech giant Huawei’s Chief Financial Officer Meng Wanzhou in Canada in December 2018 for breaking U.S. sanctions law. As Kenneth Rapoza of Forbes noted, “Huawei’s latest bad headlines show how China tech companies may have risen to prominence by copying foreign technologies in joint ventures or through white-collar criminal actions such as intellectual property theft and corporate espionage.”

Beyond the geopolitical considerations of the quiet rise of China, Trump needs a trade deal as elections loom in 2020. While the U.S. economy is currently expanding at a healthy clip and unemployment is down to 3.6 percent, failure on the trade deal could slow growth; no matter what rhetoric is used, tariffs are a tax and that tax goes right to the U.S. consumer’s pocketbook. According to the International Monetary Fund, in an all-out trade war U.S. real GDP would fall by up to 0.6 percent.

One of the areas where the trade war with China has hurt the U.S. economy the most is the agricultural sector. According to the Foreign Agricultural Service, since Trump took office and began his trade war, the total value of U.S. agricultural exports to China fell from $17.142 billion in 2017 to $11.853 billion in 2018, a decline of 31 percent. The administration, keenly aware that the agricultural sector is part of his base, provided a $12 billion bailout to farmers, but problems have mounted (including market loss to competitors and flooding).

Striking a deal is equally important for President Xi. The International Monetary Fund estimates that an all-out trade war with the United States would result in a 1.5 percent reduction in the Chinese economy. Economic growth remains a critical cornerstone for the Chinese Communist Party and Xi’s hold over the country. A sustained economic slump would raise significant problems for President Xi, including potential tensions over unemployment, concerns over pensions by an expanding population of gray hairs, and the ability of the government to deliver on social benefits. Although Tiananmen Square took place in 1989 and a repeat is a remote possibility, it remains a memory within China’s leadership, especially as it was caused by rising prices, corruption, and anxiety over the country’s future. The last two factors are evident in today’s China.

The Chinese economy has slowed for several years as the government has sought to restructure away from export-driven policies to the development of a stronger domestic economy. But the trade war with the United States is complicating the picture. According to the International Monetary Fund, China’s real GDP expanded by 6.6 percent in 2018, down from 2017’s 6.8 percent. The downward trajectory is expected to continue in 2019 and 2020.

The tightened circumstances of the Chinese economy are evident in various other indicators, probably the most challenging being high levels of debt. Over recent years, Chinese corporate leverage expanded substantially; according to the Bank of International Settlements, it stood at 160.3 percent of GDP in 2017. China’s total debt to-GDP is even larger. According to the Institute of International Finance, by the end of 2018 the combination of financial sector, government, household and nonfinancial corporate debt stood at just under 300 percent, one of the highest in the world.

The government crackdown on shadow banks and slower economic growth related to the trade war have worsened China’s debt problem as rising defaults are hitting China’s $13 billion bond market. Last year China’s corporate bond defaults tripled from 2017, and 2019 appears to be set to beat last year’s increase. According to Bloomberg, Chinese companies defaulted on 39.2 billion yuan ($5.8 billion) of domestic bonds in the first four months of this year, 3.4 times the total of the same period of 2018.

China’s unfair trade practices have also caused problems with its other trade partners. Europe has many of the same issues with China, including forced technology transfers and other restrictions on companies operating in the Asian economy. Indeed, the push Huawei Technologies made in the area of 5G has led to a number of European countries opting not to use the Chinese company. In March 2019, French president Emmanuel Macron said that there had been a European “awakening” about potential Chinese dominance on the continent, which can be seen as being led by Huawei’s dominant position in the 5G market. Suspicion over Chinese business was not helped by the January 2019 arrest of a Chinese employee of Huawei in Poland on allegations of spying.

We return to the U.S.-Chinese trade war. Both sides need a deal that allows them to claim victory. Failure on this front would most likely have a devastating impact on both economies, making it difficult for anyone to declare a victory. This leaves China and the United States in search of a deal, which is likely to paper over differences that will persist. There is enough mutual interest between Beijing and Washington to make a deal, which is good for the global economy. However, the rivalry will continue and areas like technology will continue to be at the center of U.S.-China trade and geopolitical friction.

Scott B. MacDonald is chief economist for Smith’s Research and Gradings.

Image: Reuters