How to Wage Political Warfare

Both Russia and China are governed by opaque, highly centralized and increasingly personalized governments that are well suited to the darker arts of statecraft. Political warfare, for such regimes, is second nature.

The goal, accordingly, should not be to seek the overthrow of the Russian and Chinese regimes or otherwise signal that Washington is launching a fight to the finish. But the United States will need to pursue initiatives that make life harder for the Russian and Chinese regimes by forcing them to deal with political and diplomatic challenges of America’s making, denying them a resistance-free environment within which they can pursue their geopolitical designs and otherwise driving up their costs of competition. This will be a tricky balance to strike, and it will require carefully assessing the costs and benefits of particular policies.

WITHIN THIS framework, the United States should pursue four lines of effort. First, Washington should raise the price of authoritarian governance in China and Russia. By levying targeted sanctions against high-ranking officials and businesses associated with domestic repression—senior party leaders and technology companies complicit in China’s massive detention and surveillance of Uighurs in Xinjiang, or Russian officials who spearhead the repression of opposition political groups and civil society—America can make human rights abuses costlier for their perpetrators. A bipartisan group of senators and representatives recently called on the Trump administration to pursue this approach vis-à-vis Chinese repression in Xinjiang; the Magnitsky and Global Magnitsky Acts passed by Congress in 2012 and 2016 provide a template for imposing these costs.

Another way of imposing costs is simply by exposing the corruption and repression practiced by the Russian and Chinese regimes. Such information is not only a source of embarrassment for Moscow and Beijing; it also fans fear among the ruling elites that widespread public knowledge of their misdeeds could eventually prove politically delegitimizing. It is therefore unsurprising that both regimes have been especially sensitive to reporting on their elites’ participation in corrupt and repressive acts. The Chinese government, for example, has gone to great lengths to silence the exiled billionaire, Guo Wengui, who purports to possess incriminating evidence on the Party leadership. The trust deficit in both Chinese and Russian societies is leverage that should be exploited. In a similar vein, Washington should dredge up old history that China and Russia prefer to forget. By bringing up past wrongdoing that the Chinese and Russian regimes have sought to airbrush out of their societies’ collective memories—as Secretary of State Mike Pompeo did on the twenty-ninth anniversary of the Tiananmen massacre—U.S. officials can needle Moscow and Beijing in sensitive areas.

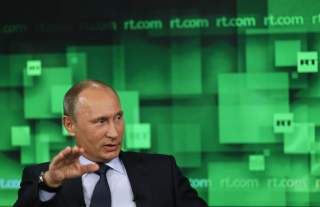

Raising the costs of authoritarian practices also means avoiding initiatives and rhetoric that confer full moral equality on the Russian and Chinese regimes. The Obama administration was right to shun (after some initial equivocation) Xi Jinping’s call for a “new type of great power relations,” which would have required Washington to accept the Chinese Communist Party’s absolute command of politics and the regime’s policies on Xinjiang, Tibet and Taiwan. U.S. officials should be equally wary about Xi’s “Chinese Dream,” a mid-century ambition that would vault China to the front ranks of great powers while maintaining the Party’s political monopoly at home. Similarly, although Russia was expelled from the G8 in 2014 for its international aggression rather than its domestic practices, it should not be readmitted to this exclusive group of democracies so long as it is a fundamentally illiberal regime that seeks to destabilize democratic governments abroad. And, of course, it is a grave mistake for the U.S. president to argue that there is no moral difference between American democracy and Russian autocracy, or to show greater respect for Vladimir Putin than for Washington’s democratic allies.

A second line of effort involves strengthening dissident or liberalizing currents within Chinese and Russian society. Such a tactic is admittedly risky: if taken too far, it could trigger harsher repression of persecuted groups or feed into Chinese and Russian narratives about foreign meddling. Yet the fact is that Moscow and Beijing already allege, and seem genuinely to believe, that America and other Western powers are fomenting anti-regime sentiment. And even limited, carefully calibrated efforts in this area may yield meaningful results.

By showing moral support to embattled religious groups, ethnic minorities and human rights activists, Washington helps keep hopes of long-term liberalization alive while also exerting ideological pressure on Moscow and Beijing. Likewise, the United States should speak out strongly in favor of free and fair elections in Russia and refrain from bestowing legitimacy on transparently flawed electoral processes; it should provide assistance to Russian ngos and civil society groups that are resisting the progressive erosion of political liberties and the rule of law.

Doing all this requires walking a careful line. The United States should avoid supporting groups that seek the overthrow of the Russian or Chinese governments or the break-up of those states; it should not “pick winners” in Russia’s electoral processes by explicitly supporting opposition candidates. It should focus, rather, on offering general encouragement to those seeking more just and humane systems, and on supporting fair political and legal processes that contribute to those outcomes.

As part of this approach, U.S. officials should also work to deprive the Russian and Chinese regimes of the information monopolies that are critical to muzzling dissent and fortifying authoritarian rule. Here understanding the information ecology behind China’s “Great Firewall” stands out as one particularly important task. While the regime has masterfully coopted the private sector and internet users—by meeting their economic needs while limiting political discourse—it has not been able to stifle dissent or stop the exchange of sensitive information. Chinese citizens recently used blockchain technology to bypass censors and share news about a vaccine scandal. While Washington should trust that Chinese citizens will find imaginative ways to circumvent censorship, there may arise opportunities to empower alienated or disgruntled social constituencies.

A third line of effort entails mounting a vigorous counteroffensive against Russian and Chinese efforts to make the world—and particularly their “near abroads”—unsafe for democracy. Frontline states in Asia and Europe have experienced intensive authoritarian influence campaigns. The United States should work with its closest allies and partners to identify Chinese and Russian political warfare as a common danger to their values and develop mechanisms to actively push back against these campaigns.

The democratic states around the Russian and Chinese peripheries deserve special emphasis here because support for these states is offensive political warfare against Moscow and Beijing. Taiwan’s political and economic vitality gives the lie to Beijing’s claims that Chinese traditions are fundamentally incompatible with democratic values. The success of democratic institutions in countries such as Georgia, Ukraine and the Baltic states helps refute Kremlin arguments about the virtues of “managed democracy” within Russia. This is precisely why Moscow and Beijing have taken such extraordinary measures—economic, diplomatic, military and otherwise—to isolate and weaken these countries. To the extent that the United States can help these countries preserve their sovereignty, security and democratic institutions, it can complicate the agendas of authoritarians at home and abroad. And to the extent that the United States and its allies can pursue vigorous—if largely non-military—campaigns to strengthen democratic governance and norms in the broader international arena, it can foster a global climate that will be increasingly uncomfortable for illiberal regimes.

Fourth, the United States must enable all these activities by rebuilding its governmental capacity to wage political warfare. The campaigns described here will require well-developed tools of influence and coordinating diverse initiatives that reach across multiple departments and agencies. This will mean increasing funding for entities such as VOA, the NED and the U.S. Agency for International Development; it will mean revitalizing the tools of public diplomacy that the U.S. government wielded during the Cold War. Equally important will be the creation of new interagency mechanisms that can routinize discussion and coordination of political warfare across the bureaucracy. All of these efforts, in turn, will require commitment and participation from the highest levels of the U.S. government: political warfare will not succeed if the president does not lend his voice and influence to that campaign.

THE UNITED States need not remain on the defensive amid intensifying Russian and Chinese political assaults; the potential for a strategically productive counteroffensive is there. But as was the case during the Cold War, political warfare will not be a cure-all, and making the most of the opportunity will require some key intellectual adjustments.

First, policymakers must become more comfortable with competition as a way of life. Waging political warfare does not mean shutting down diplomacy with Russia and China, but it does require embracing intensified competition on a sustained basis and considering approaches that have hitherto been off-limits. At the same time, U.S. policy will need to carefully distinguish between the regimes with which America is competing and the people governed by those regimes: America’s struggle is primarily with the former, not the latter, and Washington should make that point as clearly as possible.

Second, and related, policymakers must accept higher levels of risk than they have become accustomed to since the end of the Cold War. An offensive strategy, no matter how carefully calibrated, is sure to anger China and Russia. It will trigger retaliation, which is why enhanced defensive measures are also so crucial. If an offensive strategy did not bother Russian and Chinese leaders enough to trigger that retaliation, it would not be worth pursuing in the first place. Only by introducing an element of greater instability in relations can Washington compete effectively and demonstrate that it will pay a price to defend its interests.