Iran Is Making a Play to Outmaneuver the United States in Iraq

Will Iran and its allies in the Iraqi parliament use their influence to try to push U.S. troops out of the country?

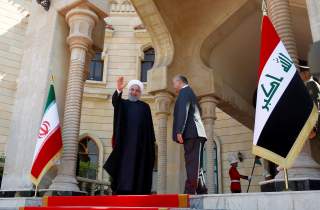

Iranian president Hassan Rouhani made a historic three-day visit to Iraq in mid-March aimed at a new chapter in strategic relations between Iraq and Iran. In a series of meetings with a cross-section of Iraqi politicians and religious leaders he sought to cement an Iran-Iraq alliance that is meant to project Iran’s power in the region after the defeat of the Islamic State. In Iraq one method Iran will use to undermine and even supplant U.S. policy is local Shi’ite paramilitary groups, one of which was sanctioned by the Treasury department in March.

At the American University of Iraq Sulaimani’s Sulimani Forum in early March Iraqi president Barham Salih addressed concerns that U.S. tensions with Iran are affecting Iraq. He stressed that U.S. troops are in Iraq to train Iraqi forces to combat terror but that there are no permanent U.S. bases in the country and there should be no other action taken by U.S. forces. It is at least the third time that Salih has sought to remind the United States about its role in Iraq after President Donald Trump said in December that the United States would “watch” Iran from Iraq.

His comments form part of a larger emerging pressure on the U.S. role in Iraq. Iran’s pro-government Press TV has stressed that parliamentarians in Iraq are seeking to pressure U.S. troops to leave. Hadi al-Amiri, head of the second larger party, is a consistent critic of the U.S. role. He formerly fought alongside the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps in the 1980s against Saddam Hussein’s regime and then came to oppose the U.S. presence after 2003. As leader of one of the most important elements of the paramilitary Popular Mobilization Units formed in 2014 to fight ISIS, his views are among the less extreme of other paramilitary-political leaders.

Qais Khazali, a former detainee of the United States at Camp Cropper, leads the Asaib Ahl Al-Haq militia; he has threatened U.S. forces and demanded they leave Iraq. Harakat Hezbollah Al-Nujaba has also threatened U.S. forces. The Pentagon and U.S. policymakers are aware of this. The February 2019 U.S. Inspector General Report on Operation Inherent Resolve against the Islamic State noted that while the PMU “played a significant role in the defeat of ISIS in Iraq, Iran’s support to many elements of the PMU has allowed Iran to maintain influence in Iraq, and the Iraqi government has been unable to assert centralized control over the PMU.” Overall the report indicates that the United States has also tracked Iranian activity in Iraq and has sanctioned four Iraqi operatives for acting on behalf of Hezbollah and the IRGC. On March 5 the U.S. Treasury department also sanctioned Harakat Hezbollah al-Nujaba.

Al-Nuajaba’s spokesman responded to the U.S. sanctions with a wide-ranging interview at Fars News. He sketched out an arc of resistance to the United States and Israel that stretches across Iraq to Syria and Hezbollah in Lebanon. The comments were indicative of a worldview common among other Shi’ite militia leaders, pro-Iranian parliamentarians in Iraq and the Iranian regime. All of it is designed to illustrate a fraternal bond between Iraq and Iran and present the United States as an outside force.

The Iranian president’s visit highlighted how close a large segment of Iraq’s most influential and powerful politicians are to Iran. It also showcased Iran’s ability to network in Iraq as Rouhani met with tribal leaders, Grand Ayatollah Ali Sistani and others. The visit came not long after Iran received a relatively positive series of comments at the Suli Forum in the Kurdish region. Iranian foreign minister Javad Zarif, who had threatened to resign last month, paved the way for the Iraq visit and said that the United States “cannot stop Iran-Iraq relations.”

The question now is whether Iran and its allies in the Iraqi parliament will use their influence to try to push for U.S. troops to leave. This would put Washington in a difficult position because the United States has invested heavily in the war on ISIS and training and equipping the Iraqi army as well as the Kurdistan region’s Peshmerga forces. The United States warned last year that Tehran would be held responsible for any attacks by proxies of Iran.

There has already been tension with members of the Shi’ite paramilitaries in Anbar and near Mosul. This is a theme frequently mentioned in Iranian media and in Iraq. Additionally, when Iraq has been challenged about the widening role of these paramilitaries and their links to Iran, there has been immediate pushback. In 2017, former prime minister Haider al-Abadi called the PMU the hope of the country and the region. He helped make sure that it became an official force, as opposed to being disbanded after the war on the Islamic State. While in the past U.S. officials in Iraq spotlighted these Shi’ite militias as a “Hezbollah model” pushed by Iran, today they have gone far beyond Hezbollah. The militias became an official force and their links to the Interior Ministry, which has been run by Amiri’s Badr Organization allies for years, puts them at the center of the security forces. They are not on the periphery, like Hezbollah ostensibly is in Lebanon. The trend appears to be that they will become like the IRGC in Iran, not like Hezbollah is in Lebanon. Like the IRGC, they will form part of a network of like-minded pro-Iranian groups stretching across Syria to Lebanon.

The comments at the Suli Forum—where Iran’s role was continually highlighted as either positive or so powerful in Iraq that it could not be disentangled—present a major challenge not only for the United States but for U.S. partners and allies in Iraq, such as voices in the Kurdistan Regional Government. However it is not clear how pressure against the U.S. presence in Iraq will manifest itself. It will likely come from parliament, as opposed to other threats. Comments by Sistani to Rouhani appeared to stress the need for “balance” in regional and international policies. The economy was on his mind, as it has been during Rouhani’s visit in general. Iran and Iraq want to boost trade to $20 billion. Iraq needs investment in reconstruction and tensions with the United States would undermine that. This is particularly true because the United States helped encourage a renewal of Saudi-Iraq relations, which began in 2017.

The larger issue will relate to U.S. plans in Syria. Iraq is key to logistics for the U.S. role in Syria. U.S. assets that track ISIS threats in the desert border area of Iraq and Syria are necessary to prevent an ISIS resurgence. This is especially true that up to thirty thousand ISIS members surrendered in Baghuz in the last months of battle and the Pentagon thinks that there may be tens of thousands of Islamic State members who have gone to ground in Iraq and Syria. Iraq therefore has a lot of leverage of the U.S. role in Syria, just as Iraq still wants a U.S. presence and U.S. investment. This tightrope could be overturned by an ill-conceived action of the Shi’ite paramilitaries if they carry through with the vocal threats that have been made over the past few years.

Seth J. Frantzman is a Jerusalem-based journalist who holds a Ph.D. from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. He is the executive director of the Middle East Center for Reporting and Analysis and a writing fellow at Middle East Forum. He is writing a book on the Middle East after ISIS. Follow him on Twitter at @sfrantzman.

Image: Reuters