Japan Stands to Gain as America Refuses Involvement in TPP-11 Trade Deal

Washington's decision to leave the trade deal would leave those markets open to Japan while America would be stuck in the cold.

Since late 2017, Japan has made impressive, rapid progress in leading a group of eleven countries in pursuing a far-reaching and historical Indo-Pacific multilateral trade agreement, known as the Comprehensive and Progressive Arrangement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (the TPP-11). This is especially remarkable after the U.S., which was thought by many pundits to be required to keep the deal on life support, stepped away from it. However, the ruptured bargain has partially revealed Japan's international economic strategy, and it has clear implications for the U.S.-Japan relationship and bilateral defense. America would be wise to rethink its involvement in TPP-11.

The first of these implications is that TPP-11 reminds Washington that Japan will pursue its economic interests even if they may have a substantial impact on U.S.-Japan defense. In hindsight, this seems obvious—but one must consider that Japan regularly agonizes over how its policy decisions affect the U.S.-Japan Alliance before making them. Indeed, many observers are not often reminded of this fact. Japan must by necessity consider the effects of its policies on an American-provided conventional defense and nuclear umbrella before risking its ally's wrath—and this makes it different from other trade partners. This often results in policies which are complementary to the United States, or at the very least carefully considered to anger America as little as possible.

Washington's push for more bilateral trade over multilateral arrangements, and its decision to impose tariffs on Japanese metals, did not change Japan's decision to stay in the TPP-11. This reveals the degree to which America has not understood Japan's valuation of TPP-11 as a national interest. Furthermore, America has not understood how future Japanese policies under similar circumstances could affect bilateral defense efforts. While not an immediate concern, this means future defense cooperation will be impacted until the immediate trade rancor is resolved.

The second implication for mutual defense is that Japan's leadership in enacting TPP-11, and in going against current U.S. trade preferences, causes American pessimists to exclusively see the pact as a Japanese economic ploy to hedge against U.S. trade pressure. This, in turn, worsens the trust between Japan and the United States. This kind of perspective also naturally causes wrinkles during defense discussions. After all, there have been few worse times for a trade dispute as China continues to militarize the Spratly Islands slowly and North Korea is far from being less of a nuclear threat than some sources claim it is.

While the TPP-11 is not the first-ever U.S.-Japan trade divergence, it certainly has been one of the more public disputes between the two allies. Moreover, despite multiple conferences between high-level trade representatives from both nations, the U.S.'s refusal to grant tariff exceptions and Japan's insistence on exacting WTO-approved retaliation does not make for an easier resolution. It is hard to make bilateral defense headway in such a climate, and economic topics risk bleeding into and poisoning defense discussions. All of this damage to the relationship also hurts the big-picture issues on which both nations agree. Worse, the TPP-11 (and the metal tariffs) give each party a clear negotiating stance if they wish to limit the progress of discussions. For instance, one can imagine the icy chill in the room after a government representative raises the topic of tariffs right after being asked about a distasteful but strategically sound defense proposal. These troubles are not likely to disappear until both the United States and Japan can resolve their differences and focus more on urgent defense issues.

The third implication of TPP-11 is an unexpected boon for Japan's nascent foreign defense sales industry. The Indo-Pacific's demographic reality—the region is home to over 60% of the world's population—and its rapidly urbanizing and consistently improving quality of life will drive the global economy for the foreseeable future. These people will need markets abroad sooner rather than later, and with those markets come defense ties. TPP-11 is a common market whose founding members’ GDPs account for $10 trillion. America stands to lose influence and defense customers to these booming domestic Indo-Pacific economies if it is not involved in the TPP-11. Furthermore, because the TPP-11 is a Japanese-led effort, it conveniently provides Tokyo new defense equipment markets with a less crowded field—just what Japan has been looking for.

While TPP-11 may throw a pall over defense discussions now, there is a high likelihood the United States will join the pact eventually, in one form or another, under one administration or another. The reasons for this are clear—Asia's burgeoning defense demands and because Japan will probably use TPP-11's economic success to entice America back to the deal in a form which satisfies Washington as the chief guarantor of Japanese security. Additionally, the chances are high that America will eventually be persuaded to associate itself with TPP-11. Further, if Japan successfully concludes an Economic Partnership Agreement with the EU by early next year as it hopes, Washington would lose a greater unacceptable level of trade influence with Japan. Therefore, the United States could be coerced back to TPP-11 sooner than it likes—or in a format it may find objectionable.

Interestingly, the mechanism for new members to join the TPP-11 after its promulgation is unclear. In fact, Japan's chief TPP negotiator Kazuyoshi Umemoto remarked how the accession of new members hasn't even been discussed but will be "once TPP becomes effective." In addition, Umemoto left the door further open for the United States by remarking "TPP is aimed at an open, rule-based, multilateral, liberal trade system so, if any country is interested and willing to abide by the rules, then we can talk about accession." It's hard to imagine other nations fitting this description as well as America. Likely, Japan will attempt to use its diplomatic clout as the de-facto TPP-11 leader to forge an accession mechanism which implicitly favors a return to the pact by the United States. In other words, Japan's decision to rebuff Washington's sideways glances at TPP-11 this spring is likely temporary.

Of particular mention is that China is not waiting to take advantage of this temporary setback in the U.S.-Japan trade relationship. On May 8, Chinese Premier Li Keqiang went so far as to write an op-ed piece in the Asahi Shimbun where he not only advocated for thawing Sino-Japanese relations but also magnanimously granted Japanese financial institutions "Renminbi Qualified Foreign Institutional Investor (RQFII)" status. That status would mean Japanese can now directly invest into the PRC's equity markets—and unknowingly assist China's insatiable thirst for foreign cash. Japanese investment would be a win for China, and it's not hard to see how it could be a loss for U.S. regional defense interests.

It is clear Japan now sees TPP-11 as a national interest and, as its de-facto leader, Japan acts as a regional shepherd committed to safeguarding its survival. With Colombia, the United Kingdom, Indonesia, and Taiwan beginning to show interest in TPP-11, this is unlikely to change soon, and neither will the agreement. A failure to recognize this could mean severe consequences for U.S. regional defense.

Major John Wright is a U.S. Air Force officer, pilot, and a Mike and Maureen Mansfield Fellow. He is a Foreign Area Officer who specializes in Japan. The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author, and not those of the U.S. Air Force, U.S. Government, Mansfield Foundation, or any foreign government.

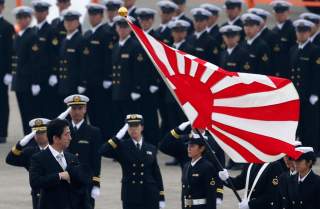

Image: Japan's Prime Minister Shinzo Abe (L) reviews members of Japan Self-Defense Force (JSDF) during the JSDF Air Review, to celebrate 60 years since the service's founding at Hyakuri air base in Omitama, northeast of Tokyo October 26, 2014. About 740 personnel and 82 military planes took part in the ceremony. REUTERS/Toru Hanai (JAPAN - Tags: POLITICS MILITARY TPX IMAGES OF THE DAY)