Let China Fail in Africa

America should continue to maintain its key African relationships and interests while China digs a debt hole.

An old African proverb warns that even the best cooking pot will not produce food. American policymakers should consider this saying as they weigh China’s growing clout and the implementation of President Donald Trump’s new Africa Strategy. But China’s economic reach in Africa is teetering on overreach. Just like the prized pot, China may not produce all that is promised. Over the last two decades, China has gained influence as it pumped billions of dollars in projects and investments across Africa focused predominantly on resource extraction and infrastructure. However, this influence comes at a cost. China may be stretching its economic largesse beyond its own capacity, jeopardizing its financial stability both at home and abroad. In July, the Financial Times noted that 234 out of 1,674 Chinese-invested

infrastructure projects announced in 66 Belt and Road Initiative countries since 2013 have encountered difficulties from labor to financing. Moreover, Africans are becoming woke to China’s more deleterious economic influence such as the Hambantota Port forfeiture in 2017 and their collective rising debt to China. China seized the port, but not without international scrutiny and over $1 billion in losses. As a result, Pakistan, Nepal and Myanmar backed away from some Chinese projects in Asia. What if multiple, similar default and seizure scenarios played out across Africa? It would be economically and politically ruinous for Chinese interests in Africa, but that could happen. If the new Africa Strategy essentially “prioritizes American interests” and seeks to counter great power influence, specifically China, but provide few additional resources to accomplish these task, then American officials should consider simply letting China financially fail in Africa.

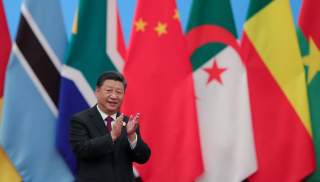

China’s Expansive Influence in Africa

Africa, referred to as the ‘empty continent’ or fēizhōu (非洲) in Mandarin, has a long, expansive history with China. This relationship reaches back to antiquity with trading routes or Silk Roads linked by the sea and land that spanned Eurasia and Africa. Those economic inroads continued into the fifteenth century marked by the successful Chinese adventurer and trader Admiral Zheng He.

In modern times, the People’s Republic of China has steadily grown in influence across the African continent. First, China was part of broader anti-colonial, pro-communist movements, then as a provider of developmental assistance. In 1999, China charted a new direction with its “Going Out” strategy that encouraged Chinese enterprises to invest overseas. Since 2000, Chinese economic growth in Africa has taken-off exponentially: imports to China from Africa have shot up twenty times, Africa now receives half of all Chinese aid, and trade between the two tops $200 billion. The success of the “Going Out” strategy was further propelled by incorporation of the signature 2013 economic Belt and Road Initiative. As part of the initiative, China has fronted a significant share of financing for the $4.5 billion Ethiopia-Djibouti Railway, the $600 million Doraleh Multipurpose Port in Djibouti, and the $3.2 billion Mombasa-Nairobi Railroad, among other projects in east Africa alone. While it is hard to piece together all the thousands of projects and investments made by China across the continent, the American Enterprise Institute estimates there have been over $298 billion in private and public loans in various sub-Saharan African countries since 2005. More importantly, China has not only become the lender of last resort for more advanced African nations, in lieu of more stringent loans and terms by lenders such as the International Monetary Fund or World Bank, but also the lender of first resort for many more, underserved nations. Moreover, initial Chinese investments have attracted other global investments from the UAE, Japan, and others that may have been reticent to invest in Africa before. Finally, investments by China have been an opportunity to improve African livelihoods and economic prospects, when leveraged properly by African nations.

Flashing Warning Signs

But as China's economic strategy for the African continent continues to unfold, recent developments indicate cause for concern. First, beyond elite-to-elite relationships, there is anxiety and a growing sense of alienation by Africans. In the last few months, anti-Chinese protests erupted in Kenya and Zambia. Africans are beginning to rebuke Chinese presence, despite an official Chinese assurance that "it is an indisputable fact that China-Africa cooperation has been sincerely welcomed by African countries and people.” One American writer in the National Review described China’s influence in Africa as “brutal and neo-colonialist,” concluding that there are just two predators in Africa: radical Islam and China. Meanwhile, others like Deborah Brautigam at Johns Hopkins believe that threats from China, such as predatory loans, land grabs, and jobs loss are overblown. But she does recognize that China “may get it wrong.” Some African leaders, such as Rwandan President Kagame are dismissive about the threat of China’s preeminence. Quoting Kagame, a Chinese official said that engagement with China is a “good thing” and "it depends on us Africans. Why wouldn't we know how to negotiate with China?"

Second, China’s financial investments appear riskier and less sustainable against the backdrop of slowing global economic growth and the ongoing trade war with America. Despite rosy predictions from Beijing, China is becoming stretched financially thin. Some speculate that China spent more than $586 billion on domestic projects to stave-off economic decline in 2008 and injected up to $1 trillion to buoy the crashing domestic stock market in 2015. Chinese officials remain tight-lipped on its internal finances, shrouded in secrecy with little information or buried in curated government reports. Meanwhile, China pressed on by financing billions in private and public loans spread over thousands of projects in various African countries. Projects usually financed with strict and surreptitious guidelines for recoupment, oftentimes linked to high profit guarantees or other forms of collateral. When Sri Lanka defaulted in 2017, it was forced to turn-over its port in Hambantota, coining a new predatory term - “debt-trap diplomacy” by one Indian analyst. Ahmed Heikal, chairman of major regional investor Qalaa Holdings, mentioned in a CNBC interview, “I don’t think that the Chinese government is aware of the backlash that

that may end up causing in the future. You can do this once, twice, three times―but if it starts being a wave of buying assets for debts, I think it can have a serious backlash and can affect the future attractiveness of Chinese investments down the line.”

Third, China now owns a significant share of debt in multiple countries because of its financing spree. China holds 88% percent of Djibouti’s $1.72 billion GDP public debt. In fact, the railway connecting Djibouti and Ethiopia cost Djibouti up to $500 million in loans to China. Wang Wen of China Export and Credit Insurance Corporation, a.k.a. Sinosure, noted that the corporation lost over $1 billion on the venture and the debt had to be restructured. Separately, Zambia owes as much as a quarter and up to a third of its debt to China. Honing in on Zambia, Ambassador Bolton warned at the unveiling of the new African strategy that Zambia’s state power utility was at risk of default and seizure for $6-10 billion in arrears to China—a charge quickly refuted by Chinese and Zambian officials. Either way, the debt dilemmas faced by Djibouti and Zambia are not isolated incidents. Kenya and others are coming to grip with their mounting debt to China. More concerning, the specter of African debt raises an important issue: the amount China is owed, domestically or internationally, is unclear. Judging by its pledges across the continent, it would seem China is oblivious to the bounds of fiscal gravity. China touted $100 million in pledges to the African Union in 2017 and $64 billion as part of a broader package in 2018. But the return on these investments or the related debt repayment regimes is unknown. Chinese officials remain silent. President Xi Jinping’s remark in September that money could no longer be used for “vanity” projects should raise eyebrows. As Chinese internal and external debts come due, a few drip-drops from a handful of missed or defaulted payments by African debtors may turn into a continent-wide deluge leaving China financially waterlogged and vulnerable with few, if any, recourses.

Chinese Default in Africa?

It is unclear whether China could handle the financial repercussions of a larger, more systemic default or debt-forgiveness program across the African continent. Seeking relief, debtors to China would likely overwhelm existing mechanisms, like international arbitration, or China-backed forums such as the Export-Import Bank of China, China Development Bank, and Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. More importantly, debt restructuring, recoupment, and, in the more extreme case, seizure may not be viable, reasonable, or sustainable for Chinese interests or presence continent-wide. Just such a dire economic scenario might push China to use its nascent military force to protect or even seize its interests. Looking back at the previous period of Great Power Competition more than a century ago, leveraging military might to force repayment was commonplace. The U.S. military made multiple incursions into Caribbean and South American nations as did the Western powers in Africa and Asia.