Problems With Russia’s Political Prepwork in the Russo-Ukrainian War

Failure to pre-position internal political forces to take political authority in the wake of Russian military advances has been puzzling and a clear detriment to the Russian war effort.

The ongoing Russo-Ukrainian War may only be in its early stages, yet deficiencies in the Russian military campaign have already been noted by political-military analysts in a variety of fora. Among the many elements of the operation that have elicited surprise, the failure to prepare the political ground in Ukraine for a future political settlement is particularly awkward. This lack of political prepwork has had ramifications for the course of the war, most critically affecting the ease by which Russia can guarantee a satisfactory off-ramp for withdrawal with its strategic aims intact. Failure to pre-position internal political forces to take political authority in the wake of Russian military advances, or even work as a fifth column in preparation for a forced negotiation, has been puzzling and a clear detriment to the Russian war effort.

Failing to Prepare the Political Ground

Having failed in the diplomatic arena, Russia’s primary war goals have been straightforwardly telegraphed since the beginning—independence for the Donbas separatist republics, the recognition of Russia’s 2014 annexation of Crimea, and guarantees of Ukraine’s military neutrality vis-à-vis the NATO alliance.

While the substantive details of the first two aims are fairly self-evident should Russia emerge victorious, the third remains mired in uncertainty as to how exactly a credible settlement along these lines would be ensured. Most hints from the Russian side have implied either a regime-change operation for the entire country or some form of partition-and-breakup as a necessary corollary to ensure that security guarantees are locked in—a considerable external imposition on the internal politics, and perhaps even the political geography, of Ukraine itself.

Prior to conflict initiation, there was considerable doubt as to what Russia’s political-territorial goals actually constituted. Between the Russian Duma’s proposal—subsequently confirmed and specified—to recognize separatist independence along existing provincial borders and the subsequent Russian finis belli to “de-nazify“ and “de-militarize” Ukraine, we still lack full knowledge of the Kremlin’s political expectations in the territorial sense. This, of course, also remains a moving target as Russia reassesses the war’s progression and the nature of its gains on the ground. For all these reasons, speculation has ranged widely.

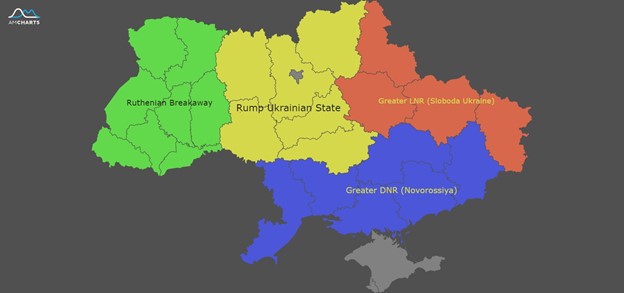

In some accounts, Russia’s territorial designs may be quite modest, consisting only of the recognition of the existing Donbas republics. Yet given the size of the war and the multiple theaters of operation, wider political-territorial goals seem more plausible. In those circumstances, the country’s partition-and-breakup into larger, nominally independent, Russian satrapies (perhaps via “greater” separatist republics) is more likely—at least as a goal for which Russian forces seem to be deployed to achieve. Indeed, this scenario could be as maximalist as a long-term occupation of part or all of the country, separated out into one or more “rump” Ukraines. The final outcome is up to considerable uncertainty, and likely diverges from any pre-planned dreams—especially given that those plans seem to have not been communicated to Russia’s factors in the country.

One Potential Dreamscape of the Partition-and-Breakup Scenario

A key problem throughout has been the absence of domestic Ukrainian readiness to accept or work for these options, so far. Bracketing the large segments of the Ukrainian population that oppose Russian designs on first principles, even the nominally “pro-Russian” elements of the Ukrainian population and the political elites that represent them have been notably unenthusiastic. And that is a genuine problem for any Russian political plan, as any occupation or regime change action involves bringing locals in, even if they remain mouthpieces for Russian political curators. The legitimacy provided by the existence of even a small subset of local authorities supporting Russian designs would at least marginally assist at dampening protest attitude behind Russian lines, even if it would not influence private opinion itself.

This lack of local elite enthusiasm is different from prior periods in Ukraine’s political history, during which genuine pro-Russian sentiment has been far stronger. The 2014 crisis resulted in Crimea’s annexation and the declaration of “People’s Republics” in the Donbas, but the political opportunity structure for more regions in Ukraine to separate from Kyiv was genuinely open at that time. Many Russian commentators expected the full breakaway of “Novorossiya,” a territory encapsulating all of Ukraine east of the Dnieper and along the southern Black Sea coast. Attempted sackings of administrative buildings in Kharkiv, Dnipropetrovsk (now Dnipro), and Odesa did not achieve their aims, but illustrated the potential of this approach at the time.

As academic researchers Quentin Bruckholz and Silviya Nitsova have independently argued, a primary factor in denying this alternative future of a proliferation of separatist republics beyond the Donbas was the agreement by urban and regional political machines to accept the new Maidan government in Kyiv. In some places, such as Kharkiv, Mariupol, and Odesa, this was the result of working with machine bosses and existing local oligarchs directly. In others, such as Dnipropetrovsk, it was due to the decisive work of oligarchs with strong networks in the region who were given direct control of the territory to manage and hunt down burgeoning separatist groups.

This was a close-run thing, according to observers, in which anti-Maidan conferences had been set up and local organizations disputed their position in the political struggle until Kyiv regained control in the early summer.

Complicating the Pétainist Option for Ukraine

Thus, although it was a “road not traveled,” in 2014 there were plenty of politicians, businessmen, and local movements that fit the bill as political successors that could have acted as an analog to Vichy France’s Marshal Pétain in a scenario of regime change or imposed rule in some broken up variant of Ukraine. While machine politicians in the Donbas were quickly overrun and local militia heads took charge, that is more difficult in a far broader territory where pro-Russian sentiment is more contested or divided. Any attempt to build up new “Peoples’ Republics” today needs a core of local elites with which to work. Unfortunately for Russia, Ukraine’s suite of pro-Russian politicians has been decimated by years of trench warfare and hostile views against Russia’s role in the post-Maidan Ukrainian political environment.

Running a Putinist Ukraine requires someone with national-level political and economic networks, especially to keep control of governments in the center and west of the country. This sort of “Vichy Ukraine“ still requires a Pétain and associated elites to run it. That is, a figure of genuine local legitimacy, even if ultimately backed by overwhelming Russian coercion.

Putting Pro-Russian Elites in a Tight Spot

In the months immediately prior to the current war, the Ukrainian political party “Opposition Platform - For Life” (OP-FL) captured most pro-Russian sentiment, articulated anti-government opposition, and collected various regional figures and businessmen in the Ukrainian east and south together. Many of the party’s members were in fact the ones that “chose” (reluctantly or otherwise) Ukraine in 2014. This is the background from which Russia would most likely select local stand-ins today. OP-FL is a clientelist party based on regional machines & business networks, and it could slot in members to run “People’s Republics” in theory.

Yet among this cohort of likely suspects, few have raised their heads so far. The leader of OP-FL, the parliamentarian and businessman Viktor Medvedchuk, who has previously been described as a friend of Vladimir Putin, was once the most obvious option. In previous years, he was a major proponent of Minsk II’s constitutional settlement. Yet little has been heard of him after he fled house arrest.

Other OP-FL oligarch-politicians, such as Serhiy Lyovochkin, Yuriy Boyko, and Dmytro Firtash, have also been noticeably quiet in expressing their old positions. As recently as January, they had started to smell political blood as President Volodymyr Zelenskyy struggled in the later winter. Yet since then, if anything, they have been at pains to signal their disagreement with the Russian war, being caught unaware by the conflict and ill-positioned to do anything other than take a carefully patriotic stance. Even so, several deputies have left the parliamentary faction since then.

So far, the only OP-FL politician who has stuck his neck out has been the curious character of Ilya Kiva, an ambitious politician from Poltava who demanded Zelenskyy’s resignation in the first days of the war. That has so far not worked out in his favor. Indeed, his own party expelled him at the end of February, with his copartisan Boyko calling him a “provocateur” seeking to “incite discord rather than promote the peace process.” By mid-March, the Ukrainian parliament passed a bill formally stripping him of his deputy mandate.

This expulsion has ultimately freed Kiva to move fully into the pro-invasion camp. For the first weeks, he primarily spoke of negotiations, a return to peace, and mused about Zelenskyy’s imminent departure from Ukraine on his Telegram channel. In more recent days, having fled to Russia, he has called for Zelenskyy’s assassination and has much more forthrightly supported the Kremlin’s invasion goals, such as they are—even while still holding that he remains a Ukrainian patriot fighting against Zelenskyy’s nationalism.