Spying through the Ages

"Twenty-first-century intelligence suffers from long-term historical amnesia."

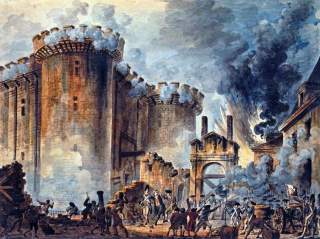

Not that 1848 had been the first time a sophisticated European intelligence and security system had been taken by surprise. In 1789, despite scandals, rampant agitation by paid street orators and countless demonstrations of public discontent, France’s Louis XVI and the vast state surveillance system he sat atop, proved incapable of foreseeing or coping with the mob action, fanned by anti-Bourbon provocateurs and pamphlets smearing the royal family, that resulted in the fall of the Bastille to a lawless, bloodthirsty mob. The virtually unopposed taking of the Bastille—a moth-eaten relic of the old regime with a skeleton garrison and only a handful of non-political prisoners—launched the revolution that would lead to the killing of the king, the Reign of Terror and the Napoleonic military dictatorship which kept Europe at war for a quarter century, ran up a pointless butcher’s bill from the Rhine to the Moskva rivers and, at the end of the day, resulted in a slightly watered-down version of the old order being restored. As a French courtier is said to have exclaimed when news of the fall of the Bastille reached the royal court at Versailles, where it was decried as a crime: “It is worse than a crime. It’s a blunder.”

Andrew’s book is peppered with such ironies, illustrating the tendency toward self-delusion in large but covert bureaucracies. Thus,

[i]n a secret speech to a major KGB conference in May 1981, a visibly ailing Leonid Brezhnev denounced Reagan’s policies as a serious threat to world peace. He was followed by Yuri Andropov, who was to succeed him as General Secretary eighteen months later. To the astonishment of most of his audience, the KGB Chairman announced that, by decision of the Politburo, the KGB and GRU were for the first time to collaborate in a global intelligence operation, codenamed RYAN – a newly-devised acronym for Raketno-Yadernoye Napadenie (“Nuclear Missile Attack”). Operation RYAN was to collect intelligence on the presumed, but non-existent, plans of the Reagan administration and its NATO allies to launch a nuclear first strike against the Soviet Union… For several years, Moscow succumbed to what its ambassador in Washington, Anatoly Dobrynin, called a “paranoid interpretation” of Reagan’s policy.

It was all the more paranoid since it occurred at a time when one of President Ronald Reagan’s top personal priorities was reaching a weapons agreement with the Soviet Union to reduce the risk of any East-West nuclear confrontation. The depth and sincerity of Reagan’s commitment and peaceful intentions were brought home to me when he added a handwritten insert to the speech I had been assigned to draft for him on the subject. It was a moving personal letter to Leonid Brezhnev urging him to join in an effort to reduce tensions on both sides of the Iron Curtain by mutually reducing nuclear arsenals. Unfortunately, by this time Brezhnev was in only marginally better shape than the aforementioned doddering Emperor Ferdinand I of Austria.

Predictably, Andropov continued this hardline position during his own short, disease-ridden stay at the Soviet helm. So did his immediate successor, who, like Andropov, quickly succumbed to illness, leading some observers to speculate on hygienic conditions in the Kremlin after three leaders of the Soviet gerontocracy in a row suddenly succumbed to the ravages of age.

Mikhail Gorbachev, the last Soviet leader—and a younger man with a reality-based view of the democratic West—reached historic agreements with Reagan, and the Russian-American thaw would continue under the well-intended, brave but overly-bibulous Boris Yeltsin, the first leader of the Russian Federation in the post-Soviet era. For better or worse, Yeltsin’s biggest problem was to be found not in intricacies of Russo-American relations, but at the bottom of many a bottle of vodka.

As for what came after Yeltsin, despite much valuable and largely accurate analysis on the precarious state of the Russian economy, fragile democratic institutions and the even more fragile state of Boris Yeltsin’s liver, the CIA was caught completely unawares. Predictable or not, the emergence of Vladimir Putin, himself an ex-spook yearning for a return to the glory days—as he sees them—of Russian stability at home, power abroad and better living through unquestioning obedience means that a still volatile nuclear superpower is now ruled by a more youthful, energetic clone of the late Yuri Andropov.

There’s plenty more déjà vu. In a bloody foreshadowing of the Soviet nightmare, Czar Ivan the Terrible created an alternative state-within-the-state in late sixteenth-century Russia. The notorious oprichniki were black-clad butchers who would massacre entire cities at their paranoid master’s bidding:

Ivan gave responsibility for identifying and disposing of traitors to his newly established imperial guard, the oprichniki, who, bizarrely, he liked to think of as a monastic order with himself as “Father Superior.” The oprichniki, though their responsibilities went beyond intelligence collection and analysis, were Russia’s first organized security service. Swathed in black and mounted on black horses, they must have seemed like a vision from the Apocalypse as they rode through Russia. Each had a dog’s head symbolically attached to his saddle (to sniff out and attack treason) and carried a broom (to sweep away traitors). A seventeenth-century silver candlestick preserved in the museum at Alexandrovskaya Sloboda shows Ivan himself on horseback with dog’s head and broom.

One bad deed deserves another. Nearly four centuries later, Heinrich Himmler, who tried to set up another black-uniformed state-within-a-state inside the Third Reich, was said to have been inspired by the example of two historical precedents: Ivan the Terrible’s oprichniki “brotherhood” and a more legitimately religious fraternity, the Jesuit Order, which at its height—before its eighteenth-century estrangement from the Vatican (and temporary disbandment)—had acted as a global “secret service” of sorts for the Papacy. In fairness to the Jesuits, their black uniforms were about the only thing they had in common with either the oprichniki or the Schutzstaffel.

On a lighter note, Andrew shares some of the secret police keyhole-peeping that went on during the Congress of Vienna and resulted in scandalous reports that rival current tabloid journalism—not to mention a certain so-called “Kremlin Dossier” alleging all sorts of overseas hanky panky on the part of one D. Trump. The Vienna reports, if equally salacious, were probably a lot more accurate, compiled and reviewed by Baron Franz von Hager, the Austrian Head of Police and Censorship at the time, before being sent on to the Chancellor and the monarch.

After [Foreign Secretary] Castlereagh’s return to London, the British embassy in the Starhemberg Palace and the British plenipotentiary’s residence were transformed, according to police reports, into combinations of “brothel and pothouse”, where actresses and chambermaids worked as prostitutes. Police reports on behaviour at the Russian embassy, where one of the valets was [an Austrian] agent, were even more censorious. According to a report by “Agent D” forwarded to Hager on 9 November, “the Russians lodged at the [Hof]burg, not content with keeping it in a filthy condition, are behaving very badly and constantly bringing in girls.” One officer in the Tsar’s entourage tried to blame Russian bad behavior on “the unbelievable depravity of the female sex of the [Austrian] lower orders.”

More than a century later, the local Viennese, no longer blessed with a “Head of Police and Censorship” of their own, would once again be heard complaining about the sexual mayhem being committed by Russian members of the joint allied occupation of Austria in the years immediately after World War II.

In those early postwar years, with Josef Stalin still firmly in charge in the Kremlin, murder was a routine intelligence tool applied on a massive scale. Some intended victims were luckier than others, as is attested by one of the excellent illustrations included in The Secret World. In it, a still relatively young Marshal Tito, the Yugoslav strongman who brought his country out of the Soviet orbit without renouncing Communism as a socio-economic system, is pictured with a smiling, swarthy rather oily-looking gentleman, the caption explaining that “…Tito (left), receives the Costa Rican envoy, ‘Teodoro B. Castro’, in 1953, unaware that ‘Castro’ is a Soviet illegal (real name Iosif Grigulevich) planning his assassination – a mission aborted after Stalin’s death.”

Saved by the bell.

Another illustration, this one a color reproduction of an oil portrait, identifies “[t]he first known transvestite spy, the flamboyant French Chevalier d’Éon de Beaumont (with five o’clock shadow), who enjoyed his life in London so much that for some time he refused instructions to return to France.” Professor Andrew enlarges on the Chevalier’s curious career in his text, explaining that he was able to tie down a French pension despite his insubordination because he possessed documentary evidence of a secret plot by King Louis XV to invade England, concocted behind the backs of his government ministers by the monarch’s very private, personal espionage bureau known, appropriately enough, as “Le Secret du Roi” (King’s Secret).

Pierre-Augustin Caron de Beaumarchais, the celebrated (“Marriage of Figaro”) playwright who also moonlighted as an ancien regime espionage agent, was sent to London to cut a deal with d’Eon securing his permanent silence. Under terms of the resulting “transaction,” d’Eon was required to announce that he was, in fact, a woman, and agreed—perhaps a little too eagerly—to dress as one for the rest of his life.