The War over Liberal Democracy

The Catholic medieval project, for all its achievements, ultimately failed to uphold one of the most transformative ideas of the Jewish and Christian traditions: the freedom and dignity of every human soul.

This aggressive stance was in fact fueled by anxiety, a deep insecurity about the integrity of the entire medieval project. One expression of the insecurity was the impulse to censor: the creation of the Index of Prohibited Books. Another was the impulse to dogmatize: the construction of rigid boundaries defining acceptable belief. A third tendency was to exclude: the marginalization of dissenters from civic and political life. The latter impulse helps to explain European anti-Semitism, what historian Paul Johnson has called “a disease of the mind.”

The disease spread like a plague throughout the latter Middle Ages, when power struggles with the state, clashes with Islam and the growth of new heresies combined to put the church on the defensive. Patristic and medieval sources offered a basis for the toleration of Jews in Christian society. Like Muslims, Jews were to be tolerated in the hope that they could be persuaded to convert to Christianity. Throughout the Middle Ages, the papacy opposed their forced conversion, and they enjoyed a qualified autonomy in their practice of Judaism.

Yet, beginning in the thirteenth century, writes historian Mark Cohen, papal protection for the Jews was replaced by “hostility and a strong desire to exclude the infidel Jews from the company of Christians.” Other medieval texts justifying the use of force against Jews—accused of the “ritual murder” of Christian children—came into play. Dress codes entered authoritative canon law under Pope Gregory IX. Jews increasingly fell under a shadow of suspicion and endured outbursts of intense violence. During the Black Death in the 1340s, for example, Jews were massacred across Germany, Flanders and elsewhere. Copies of the Talmud were burned, and many Jews were forcibly converted to Christianity. The polices of subjugation, restriction, and exclusion finally led to expulsion: beginning in England (1290), followed by France (1306), Portugal (1496), Provence (1498), Saxony (1536), Bohemia (1541) and the Papal States (1569). In 1492, under the sway of the Spanish Inquisition, Spain ordered the expulsion of its entire Jewish population, roughly 200,000 people. Tens of thousands of refugees perished trying to find safe haven.

The apologists for Christendom either ignore these excesses wholesale or argue that they were negligible compared to the atrocities of the twentieth century—and quite modest compared to the legal practices of medieval Europe. As one canon lawyer put it recently for the National Review: “torture was ubiquitous in courts of the time, and the Inquisition’s use of it, while objectively horrific, was downright progressive when seen in context.” All of this evades the crux of the crisis: the transformation of the gospel, with its message of divine love and spiritual freedom, into an ideology based on exclusion and subjugation.

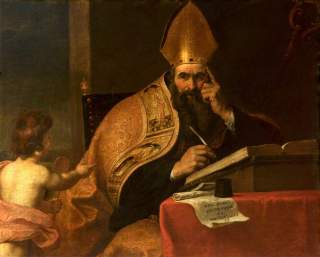

A small but growing number of thinkers discerned a spiritual malaise overshadowing the church. The Roman See managed to silence the voices of Jan Huss and John Wycliffe, but it had a much more difficult task in the person of Desiderius Erasmus (1466–1536), a classical scholar and a Catholic theologian who defined for generations the reform movement known as Christian humanism. Erasmus used the tools of classical learning to draw believers into a deeper knowledge of Scripture, especially the message of the gospels, which he believed had been effectively abandoned in much of European society.

Nowhere was this deficit of piety more glaring than in politics. In The Education of a Christian Prince, Erasmus argued that a prince is set above his subjects politically, but not morally. The prince, in fact, is “a man ruling men, a free man ruling free men and not wild beasts.” It is “a mockery,” Erasmus wrote, when rulers “regard as slaves those whom Christ redeemed with the same blood as redeemed you, whom he set free into the same freedom as you…” Elsewhere he asked: “What makes a prince a great man, except the consent of his subjects?” In all this, Erasmus anticipates the Lockean model of consensual government.

Likewise, the church and its ecclesiastical leadership came under a withering assessment. In works such as In Praise of Folly, Erasmus lambasted the moral turpitude of clerical leadership: the warrior popes, heresy trials, priestly concubines and lust for wealth and worldly power. “If Satan needed a vicar he could find none fitter than you,” Peter tells Pope Julius at the gates of heaven. “I brought heathen Rome to acknowledge Christ; you have made it heathen again.” Although Erasmus never developed a theory of religious freedom, he condemned the persecuting temper of Rome. “Compulsion is incompatible with sincerity,” he wrote, “and nothing is pleasing to Christ unless it is voluntary.”

Erasmus called his reformist vision “the philosophy of Christ,” meaning a thoroughgoing return to the life and teachings of Jesus. The gateway to personal and social renewal, he argued, was the Bible, which must become as familiar to laymen as it was to priests and bishops. In 1516, Erasmus produced a revolutionary translation of the New Testament, based on a study of original Greek manuscripts. His text cast doubt on the accuracy of the Latin (Vulgate) translation, first made by Jerome in 382 and endorsed as authoritative by the church.

The work set off a storm of controversy. One critic warned that if the Vulgate was in error, “the authority of theologians would be shaken, and indeed the Catholic Church would collapse from the foundations.” According to biographer Johan Huizinga, Erasmus appeared to many admirers as “the bearer of a new liberty of the mind.”

Disaffected by the materialism of the church, an Augustinian monk named Martin Luther (1483–1546) became emboldened by the example of Erasmus, whom he regarded as “our ornament and our hope.” Erasmus’ Greek New Testament arrived in Wittenberg just as Luther was lecturing on the book of Romans. It became the working text for his own translation of the Bible into German, the publishing event that shattered the hegemony of the Catholic Church.

More than 150 years before John Locke attacked the Hobbesian concept of an all-powerful Leviathan, Luther led an assault on the “tyranny of Rome” and its “perverse leviathan” of religious mandates that reduced the faithful to slavery. Luther’s watchword was freedom, proclaimed in his incendiary tract, “The Freedom of a Christian.” “One thing, and only one thing, is necessary for Christian life, righteousness, and freedom,” he wrote. “That one thing is the most holy Word of God, the gospel of Christ.”

By forcibly controlling the interpretation of Scripture, Luther claimed, the Roman Curia was proving itself “more corrupt than any Babylon or Sodom ever was.” By elevating its priestly class and demanding obedience to its teaching on works, penance and pilgrimage, the church had degenerated into “so terrible a tyranny that no heathen empire or earthly power can be compared with it.”

Luther’s doctrine of the “priesthood of all believers”—a message of spiritual freedom and equality—was violently at odds with the entire superstructure of Christendom. Under the medieval system, only the monastic orders, with their vows of celibacy and poverty, could produce the “spiritual athletes” of the church. While modern admirers like Rod Dreher hope to recapture the monastic spirit, Luther experienced the monasteries as hotbeds of avarice and pride. He abolished them. “Here Christian brotherhood has expired and shepherds have become wolves,” he complained. “All of us who have been baptized are priests without distinction.”

The papal bull of 1520 excommunicating Martin Luther from the Catholic Church accused him of promoting forty-one heresies and “pestiferous errors.” One of the alleged errors was his view that “the burning of heretics is against the will of the Holy Spirit.” Luther’s challenge to the church involved not only a disagreement about the gospel and the authority of the Bible; it set off an enduring debate in the West about the rights of individual conscience in matters of faith.

Finding inspiration in the example of the first-century Christians, Luther elevated the individual believer, armed with the Bible, above any earthly authority. This was the heart of his defiance at the Diet of Worms: “My conscience is captive to the Word of God. I cannot and I will not recant anything, for to go against conscience is neither right nor safe. Here I stand.” Neither prince nor pope could invade the sanctuary of his conscience. This, he proclaimed, was the “inestimable power and liberty” belonging to every Christian.

Over the next two centuries, every important advocate of political equality, pluralism and religious freedom in the West would enlist Luther’s insights. Yet no one did so to greater effect than English philosopher John Locke (1632–1704). Combining Luther’s defense of individual conscience with the Erasmian “philosophy of Christ,” Locke imagined an entirely new political community: a society that guaranteed equal justice to all of its citizens, regardless of religious belief.

Locke’s career is central to the story of how the West defeated two of the most intractable problems of medieval European society: political absolutism and militant religion. In seventeenth-century Europe, the problems were inextricably linked; both drew nourishment from eccentric interpretations of the Hebrew and Christian Scriptures. No progress toward a more liberal and tolerant society was possible, Locke reasoned, without a revolution in the theological outlook of political and religious authorities.