Will the Chinese Century End Quicker Than It Began?

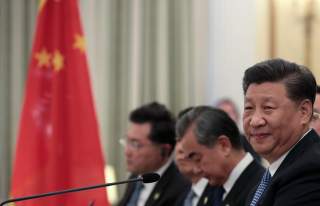

China’s new paramount leader, Xi Jinping, has completely discarded the low-key diplomacy of his predecessors in favor of an all-out bid for global primacy.

Reflecting on the future of the global order, the late Singaporean prime minister Lee Kuan Yew warned that the rise of China is so consequential that it won’t only require tactical adjustment by its neighbors, but instead an overhaul in the global security architecture. As the former Asian leader bluntly put it, though “[t]he Chinese will [initially] want to share this century as co-equals with the U.S.” they ultimately have the “intention to be the greatest power in the world” eventually.

Not long after the demise of the Singaporean leader, his prophetic insights are congealing into an indubitable geopolitical reality. Today, China is the world’s largest exporting nation, the largest consumer of basic goods, and increasingly also the leading source of investments, particularly in strategic infrastructure, especially in Asia and across the developing world. Meanwhile, economic vigor has translated into strategic assertiveness and military muscle, as China opens up overseas bases, beginning in Djibouti but more stealthily across the Indian Ocean, expands its blue water navy, and coercively transforms adjacent waters into its “blue national soil.”

Above all, China’s new paramount leader, Xi Jinping, has completely discarded the low-key diplomacy of his predecessors in favor of an all-out bid for global primacy, going so far as promoting a “uniquely Chinese model” of development overseas and gradually establishing an ‘Asia for Asians’ order across the Eurasian landmass to the exclusion of Western powers and Japan. Though packaged as ostensibly a trillion-dollar connectivity initiative, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is, above all, about laying the foundation of a ‘Chinese world order.’

Though far from hegemonic, the Chinese came closest to ruling the high seas before the advent of European imperialism. The dual-ocean voyages of Zheng He, a Muslim admiral from the Ming Dynasty who extensively relied on the expertise of co-religionist seafarers, underscored the inherent inseparability and thick networks of commercial and cultural interdependence across the Pacific and Indian Oceans. But does this century belong to China? There are three reasons to be skeptical.

The Resilience of American Primacy

Nowadays, it’s fashionable to talk about the “Chinese Century.” Yet, China’s bid for strategic primacy is taking place within a period of American strategic resurgence, particularly under the Donald Trump administration, which has shown far less self-restraint in challenging China.

Conventional views on the Trump administration portray a picture of American strategic retreat, especially given the American president’s unpopularity in the region as well as his decision to nix the TPP deal. A more nuanced analysis, however, reveals a more complex picture.

On one hand, Washington has stepped up its Freedom of Navigation Operations (FONOPs) and nuclear bomber aerial patrols across the South China Sea, openly defying China’s excessive territorial claims in the contested maritime space. The Trump administration has given greater leeway to Pentagon to check China’s maritime assertiveness, including on decisions concerning freedom of navigation operations (FONOPs). Even the U.S. Coast Guard has joined in, putting further pressure on Chinese maritime expansionism.

Washington has also doubled Foreign Military Financing to key regional allies, including the Philippines, openly called on China to remove advanced military assets in the disputed South China Sea, and even treated China’s paramilitary forces operating in the area as de facto extensions of the PLA Navy. In fact, the Trump administration also made the unprecedented decision to openly suggest that it will come to the Philippines’ rescue in the event of a conflict with China in the South China Sea.

With the support of the U.S. Congress, the Trump administration has also expanded its strategic engagement with the region through the multi-billion dollar Asia Reassurance Initiative Act (ARIA), which augments American defense and military footprint and diplomacy in the Indo-Pacific region, as well as the $60 billion Better Utilization of Investments Leading to Development (BUILD) initiative, which aims to mobilize high-quality American investments across strategic markets in the region, particularly in East Asia.

On the trade front, the United States has openly sought fundamental changes in China’s trade and industrial policies, questioned the viability of the BRI, and pressured allies and partners to shun risky Chinese high-tech investments, particularly in strategic sectors. While the relative gap between Beijing’s and Washington’s economy and military has dramatically narrowed in the past decade, China still lags far behind the United States in terms of net stock of resources including soft power, technology, manpower, military hardware, economic resources, and natural endowments and precious minerals, which can be mobilized in periods of conflict.

Collective Strength of the Alliance

As scholars such as Michael Beckley have noted, “a nation’s power stems not from its gross resources but from its net resources—the resources left over after subtracting the costs of making them.” China also faces massive internal structural challenges, including an impending demographic winter, rising social unrest, a growing environmental crisis, and imbalances in the real estate and banking sector.

Nonetheless, America’s political paralysis at home is also a major source of concern. Yet, the latest surveys show that most people of the world still prefer the United States to China as the global leader. But what truly augments America’s edge over China is its broad and surprisingly durable network of regional alliances, particularly with middle powers Japan, Australia and, increasingly, India, which share common, though not identical, concerns over China’s rising assertiveness.

In fact, other regional powers, namely Japan and Australia, which are committed to a “free and open” Indo-Pacific, support the U.S.-led pushback against China. It’s within this context that one should understand Japan’s successful efforts, in tandem with Australia, in resuscitating the TPP agreement, which Trump perfunctorily ditched.

In fact, Japan ($240 billion) continues to beat China ($210 billion) in terms of quality and scale of infrastructure development in Southeast Asia and the broader region. Australia and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) have also signed an investment agreement, which aims to “develop a pipeline of high-quality infrastructure projects, to attract private and public investment.”

India is separately expanding its developmental assistance to and strategic cooperation with ASEAN countries. Rather than relying on American instructions or initiatives, each of these middle powers is engaging ASEAN nations either together or individually to help build a “rules-based” order in the Indo-Pacific. In contrast, China hardly has a single reliable ally to promote its vision and values for the region. In fact, both North Korea and Pakistan, considered Beijing’s closest strategic partners, have sought to diversify their external relations in recent years.

Small Powers Strategic Astuteness

While Pyongyang has sought direct negotiations with Washington, largely for the removal of punitive sanctions on its flailing economy, Islamabad, in turn, has pivoted to Saudi Arabia, not to mention that it continually relies on the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for financing to reduce its excessive dependence on and ballooning debt due to the BRI. China simply has no capable and reliable allies.

Moreover, we should look at sustained efforts by Southeast Asian nations to diversify their strategic partners and sources of foreign investment. Though known for their historical tensions with the West, the leaders of Malaysia (Mahathir) and the Philippines (Duterte), not to mention the communist leadership in Vietnam, have welcomed closer strategic cooperation with and investments from the United States and, most importantly, Japan.

Even poorer Southeast Asian nations such as Myanmar, Cambodia, and Laos have proactively sought Japanese developmental and infrastructure investments to reduce their reliance on China. Southeast Asian nations, both small and larger, have jealously guarded their post-colonial quest for strategic autonomy, playing one great power against the other while seeking to avoid overreliance on a single foreign power.

Overall, both low and middle-income Southeast Asian countries have assiduously sought, whether on a bilateral or multilateral (via the ASEAN mechanism) basis, diversified strategic relations with Indo-Pacific powers, from India and Russia to Japan, China and the United States, as well as sources of investment and aid.

This only shows that Southeast Asian nations aren’t pawns on a geopolitical chessboard. Instead, they are active players with a considerable agency in shaping their own strategic destiny. The upshot of this highly dynamic and contested strategic landscape is the emergence of multiple centers of power and varying degrees of strategic freedom accorded to each state, thus no single power can fully shape the regional security, economic, and diplomatic agenda.

Authoritative surveys across Southeast Asian nations show that seven out of ten respondents hold negative views of China’s BRI, while less than half expressed confidence in China’s ability to play a constructive leadership role in the region. The most trusted nation in the eyes of Southeast Asian nations remains Japan. China is undoubtedly a major player in the region, but far from its inevitable hegemon.

Richard Javad Heydarian is an Asia-based academic, currently a Research Fellow at National Chengchi University (Taiwan), formerly an Assistant Professor at De La Salle University, Philippines; and author of, among other works, The Rise of Duterte: A Populist Revolt against Elite Democracy and The Indo-Pacific: Trump, China, and the New Struggle for Global Mastery.