As European Countries Celebrate Passover, Easter, and Ramadan, This Is How They're Regulating Religious Worship

Religion in the time of social distancing.

In response to the coronavirus pandemic, most European countries have imposed unprecedented confinement measures on their populations, banning social gatherings and closing public spaces.

Many forms of religious worship require collective participation and physical proximity between participants. So there is a strong public health impetus to ban religious celebrations and to close places of worship to stop the virus spreading. This is especially true as the world’s three major monotheistic traditions prepare for the mass celebrations of Passover, Easter and Ramadan.

The European Convention on Human Rights stipulates that freedom of religion can be subject to certain limitations, including where necessary in the interests of public health. In practice, the restrictions European states have been willing to impose on places and practices of religious worship during this crisis vary considerably.

Given that the mode and risk of viral transmission is the same in all these countries, why is there such a divergence in public policy?

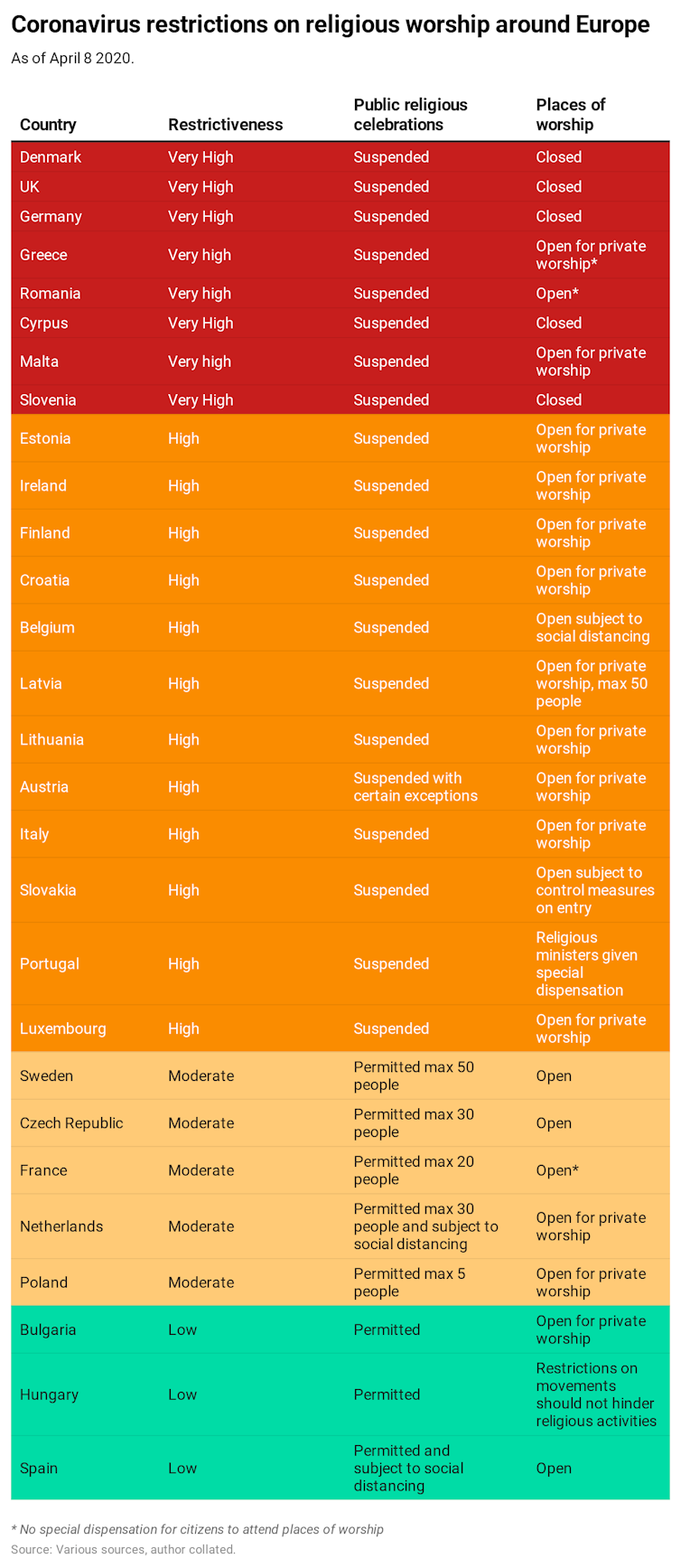

As part of my ongoing research on the sociology of religion in the context of the coronavirus pandemic, the table below offers a review of restrictions imposed on collective religious worship in the 27 EU member states and the UK as of April 8. For the purposes of analysis, these policy approaches are grouped into four levels of restrictiveness.

Certain states, such as Germany and the UK, have imposed very high levels of restrictiveness, effectively curtailing private prayers in public places as well as public religious celebrations. A second, larger, group including Italy and Finland, have imposed high levels of restrictiveness: suspending public celebrations but allowing for private prayer to be accommodated in places of worship.

Yet others, such as Sweden and France, have adopted a moderate approach, allowing public celebrations to take place so long as they don’t exceed a maximum number of participants. A small group of EU states, including Spain and Hungary, have opted for low levels of restriction on religious worship. In this last group, some religious authorities have elected to impose more stringent restrictions than those minimally required by law.

Levels of secularisation

Modern secular states developed in Europe by gradually displacing dominant religious authorities from the public sphere. As secular states grew in power during the 19th and 20th centuries, the social spaces and times allocated to religious expression shrank, and these were increasingly restricted to the private sphere.

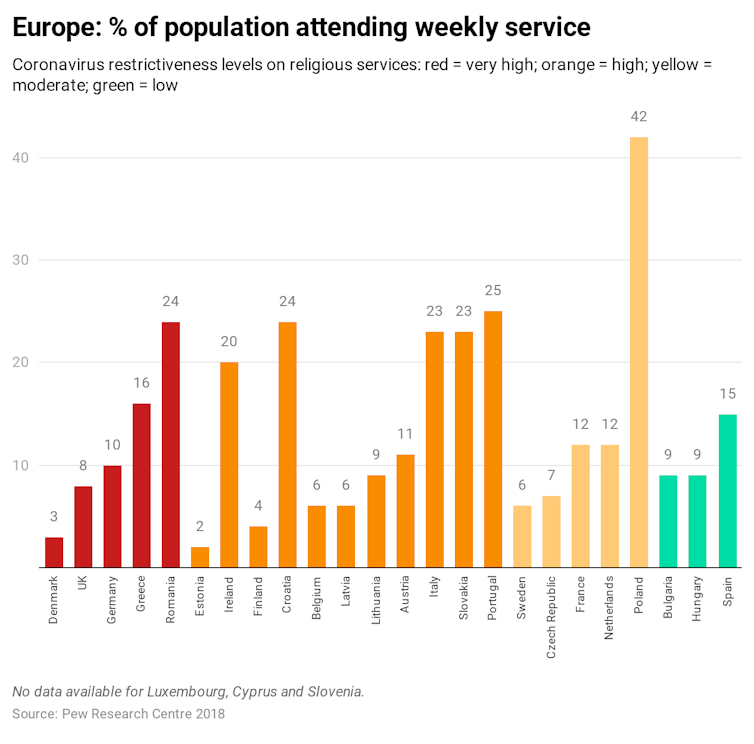

In line with this historical trend, we might expect to find the most restrictive measures on religious worship in the most secular European countries – either those where religion is formally disestablished from the state or those where observant religious persons form a small minority of the population. But that is not the case.

While more than 20% of people in Italy, Slovakia, Portugal, and Romania attend weekly religious services, all have imposed high or very high levels of restrictions on collective religious worship. In the UK, where the head of state is also the head of the established Church, restrictions are also very high.

Conversely, Bulgaria and Hungary have implemented very minimal restrictions on publish religious celebrations, even though only 9% of their respective populations attend weekly services. And the notoriously secular state of France has imposed some of the more moderate religious restrictions in the EU.

Democratic freedoms

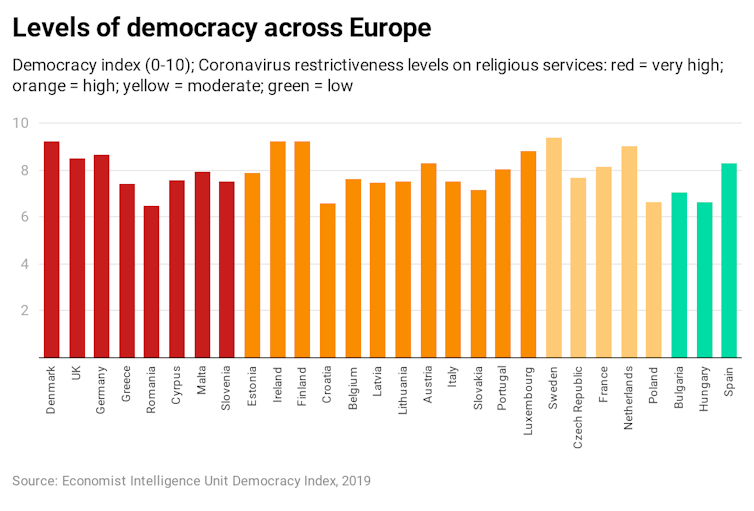

The relative penetration of democracy in each country could also provide another explanation for the divergences in restrictiveness. The free exercise of religion is a basic or fundamental principle in both the liberal tradition and the republican tradition of democracy. So we might expect less democratic states be be more prone to restricting this freedom. But again, there is no discernible trend, as the graph below shows.

Those states identified as most democratic, with a score of more than nine on the Economist Intelligence Unit’s Democracy Index, exhibit a range of levels of restrictiveness regarding public religious worship in the context of COVID-19: the Netherlands (moderate), Sweden (moderate), Finland (high), Denmark (very high). A similar variation can be observed in those states which score low on the index.

Read more: Coronavirus: why the Nordics are our best bet for comparing strategies

A moving situation

As the progression of the virus continues to evolve at speed across Europe, state responses to the pandemic remain dynamic. Poland, for example, recently reduced the maximum number of worshippers authorised to participate in a celebration from 50 to five. In Greece, the Orthodox Church has filed for a cancellation of the ban on religious services on constitutional grounds. Other states are also likely to relax or increase restrictions depending on their internal situations. Further monitoring is therefore needed to track whether the current restrictions are maintained.

The national contexts in which emergency restrictions are implemented are also key. While countries may impose relatively few direct restrictions on religious liberties, they may have other restrictions which curtail religious practice.

For example, while France has not explicitly ordered the closure of places of worship, the severe restrictions it places on residents’ movements may prohibit the faithful from exercising their right to visit places of worship. There have also been reported cases of arbitrary variances in implementation within countries where some regions or minority groups are subject to greater restrictions than others.

Religious freedom is just one of the basic liberties which European states continue to suspend as they cede emergency powers to executive governments in the name of public health. In these extraordinary times, there is a grave risk that these exceptional measures may become normalised. To guard against this risk, it’s crucial to continue monitoring the restrictions which states impose on citizens, to recall their unprecedented nature, and to question their justification.

![]()

Alexis Artaud de La Ferrière, Senior Lecturer in Sociology, University of Portsmouth

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Image: Reuters.