Why The Federal Reserve Accepted 2 Percent Inflation As The Norm

The Fed’s message that rates will stay near zero for a long time—and that inflation will be allowed to exceed 2 percent to make up for past misses—is meant to increase inflation expectations.

The unanimous decision of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) to shift from inflation targeting to average inflation targeting is another step away from its mandate to achieve long‐run price stability. Section 2A of the Federal Reserve Act does not say the Fed’s long‐run objective should be 2 percent inflation. It calls for maintaining the growth of money and credit to “promote effectively the goals of maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long‐term interest rates.” The legal basis for price stability has not changed, but the Fed’s interpretation of that responsibility has drifted, so that “price stability” now means an increase in the price level (P) that averages 2 percent over time, with the proviso that the average inflation target (AIT) must be “flexible.”

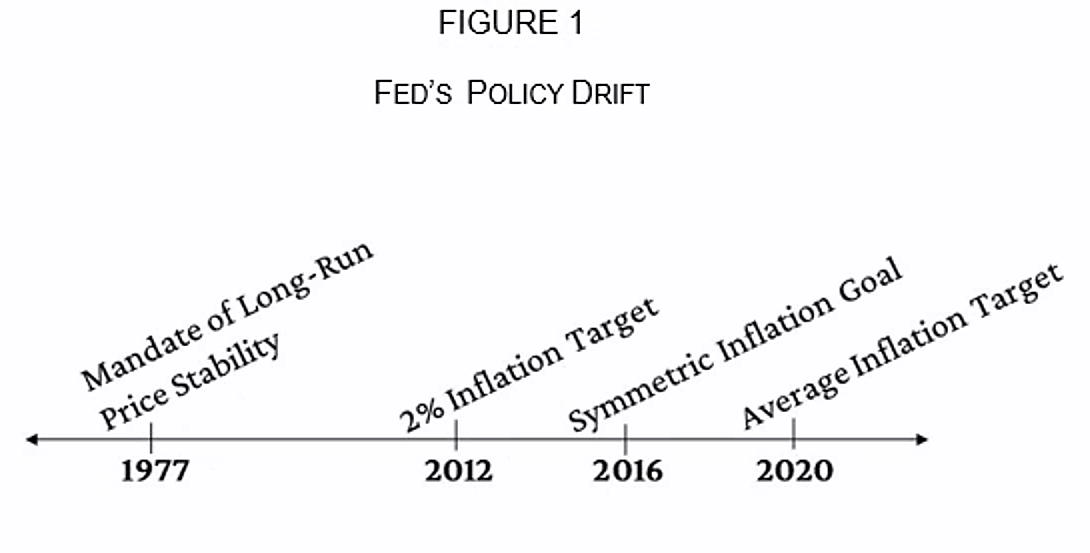

The Fed began to target inflation in 2012, when it moved to a 2 percent inflation target (IT), specified in the FOMC’s “Statement on Longer‐Run Goals and Monetary Policy Strategy” (also known as the “Consensus Statement”). In 2016, the Fed added flexibility to its IT by adopting a “symmetric inflation goal”; and, in 2020, the Fed amended its Consensus Statement and moved to a 2 percent average inflation target (AIT), announced by Fed Chairman Jerome Powell on August 27, at the Jackson Hole Conference. This policy drift is shown in Figure 1.

Price Stability Mandate

As former Fed governor Robert Heller notes: “The congressional mandate as stated in the Federal Reserve Act of 1977 is for the Fed to provide for ‘stable prices’—not 2 percent annual price increases.”

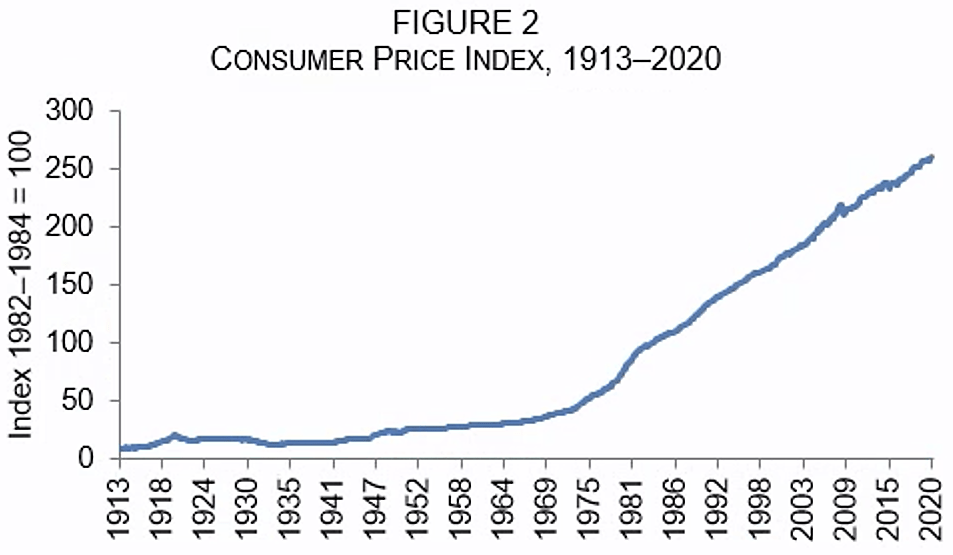

The term “stable prices” refers to a stable average level of money prices, not a stable rate of change of that level. It is problematic that so many people, Fed officials included, fail to make this distinction. The law of compound interest tells us that even a relatively low rate of inflation can have a considerable influence on the price level over time. For example, a 2 percent IT means that the average level of money prices doubles every 35 years thereby debasing the currency. If the time frame for an AIT of 2 percent is 35 years, then the price level will also double under the Fed’s new monetary framework.

Average Inflation Targeting

Despite the literal meaning of “stable prices,” the Fed has long equated fulfilling its mandate with achieving 2 percent inflation, while implicitly treating “maximum employment” as that employment level consistent with its 2 percent target. Yet it has not even succeeded in keeping the price level rising at a steady 2 percent trend. During the 1970s, inflation soared to double digits at the same time unemployment was rising; the result was stagflation. Paul Volcker brought inflation down and laid the basis for solid economic growth. Today, the Fed sees low inflation as a problem. The central bank has not been able to achieve its 2 percent IT since 2008, and its policy rate is at the zero lower bound (ZLB). Hence, since 1977, the trend of the price level has first drifted upwards and, since 2008, downwards.

The Fed has instituted AIT with the hope of keeping the trend of the price level stable—that is, “making up” for drift. Provided it is done with a reasonably short averaging “window,” AIT could indeed make the price level (P) more predictable than ordinary IT, precisely because it would eliminate P “drift” altogether (see Selgin). However, if the window is very long, or indefinitely so, and AIT is “asymmetric,” price level drift could instead end up becoming even more pronounced. As Selgin notes,

Faced with stiff‐enough opposition, the Fed might fail to carry out some or all of a needed correction [from overshooting its 2 percent AIT]. …Because the Fed’s efforts to make up for excessively low inflation are less likely to meet with similar opposition, the result could be an “asymmetrical” average inflation targeting strategy that allows the price level path to drift upwards. In that case, even if the Fed starts out with a clearly‐specified AIT rule, its reluctance to stick with it will cause the long‐run inflation rate to exceed the Fed’s target.

In his Jackson Hole speech, Chairman Powell made it clear that the central bank will follow a “flexible form” of AIT, leaving the “average” undefined. Consequently, a serious flaw with the new monetary framework is that, without a specific time frame, the term “average” is so open to abuse as to be almost meaningless. Without pinning down the time frame, it is impossible to say the AIT has been violated—merely, that the path of the price level is not on target.

Under the new framework, we can expect more than 2 percent inflation for some unspecified period to make up for shortfalls over another unspecified period, and vice versa. However, it will be difficult to return to 2 percent inflation once the Fed lets it drift above 2 percent. Congress is unlikely to tolerate the rise in unemployment and social unrest normally associated with disinflation in a world of sticky prices.

More importantly, average inflation targeting further expands the Fed’s discretionary authority. There is still no credible monetary rule to guide policy and anchor the long‐run price level. In this sense, Congress has failed in its duty to safeguard the purchasing power of the dollar—an important property right (Figure 2).

Note: Consumer price index for all urban consumers: all items in U.S. city average. Source: St. Louis Fed, FRED.

Rethinking the Fed’s Monetary Framework

In addition to price stability, the Fed has been tasked with achieving “maximum employment.” Just as the definition of “stable prices” is ambiguous—because it could reflect a stable rate of change in the price level or a stable price level—the term “maximum employment” has never been precisely defined.

Under the influence of the Phillips curve, policymakers assumed a tradeoff between unemployment and inflation: reducing unemployment was presumed to lead to higher inflation, at least in the short run. Since policymakers typically are myopic, they tried to exploit that tradeoff. However, under the new monetary framework, Chairman Powell and the FOMC have declared that the Phillips curve is flat and no longer a reliable policy guide. According to Powell, “a robust job market can be sustained without causing an outbreak of inflation.” Under the new framework, therefore, the Fed will not automatically increase its policy rate as the labor market heats up. In effect, greater weight is now being given to reducing unemployment and less to damping inflation expectations.

Logic Behind the New Framework

The logic behind the new framework is provided in Chairman Powell’s Jackson Hole speech. He explains that, while the public often considers low inflation preferable, persistently low inflation can lower long‐run inflation expectations. This becomes an issue when one considers that expectations directly influence the level of nominal interest rates. For a Fed that has consistently undershot its 2 percent long‐run inflation target, this is rightfully concerning. Without some force putting upward pressure on interest rates, the Fed will continue to operate with a reduced range of options, due to its proximity to the ZLB.

Questioning Conventional Wisdom

Claudio Borio, head of the Monetary and Economic Department at the Bank for International Settlements, has argued that erratic monetary policy can contribute significantly to financial booms and busts, impact resource allocation, and slow productivity growth. In his view, “the long‐term decline in real interest rates since at least the 1990s may well be, in part, a disequilibrium phenomenon, not consistent with lasting financial, macroeconomic, and monetary stability.” As he states:

The long‐term decline reflects, in part, asymmetrical monetary policy over successive financial and business cycles. Global disinflationary forces, in the wake of the globalization of the real economy and technological innovations, have kept a lid on inflation. Monetary policy has failed to lean against unsustainable financial booms. The booms and, in particular, subsequent busts have caused long‐term economic damage. Policy has responded very aggressively and, above all, persistently to the bust, sowing the seeds of the next problem. Over time, this has imparted a downward bias to interest rates and an upward one to debt, as indicated by the steady rise in total debt‐to‐GDP ratios.

For Borio, “[low] policy rates are not simply passively reflecting some deep exogenous forces; they are also helping to shape the economic environment policymakers take as given.” The Fed’s adherence to “lower for longer” is a case in point. The reach for yield (see Banerji; also Goldfarb and Minczeski) in an environment of near‐zero interest rates, engineered by the Fed and other central banks, can foster financial booms and slow productivity growth, thereby putting downward pressure on real rates.

Finally, Borio notes that “the well‐known limitations of expansionary monetary policy in tackling busts appear in a new light. It is not just that agents wish to deleverage and the transmission through banks is broken; easy monetary policy cannot undo the resource misallocations.” What needs to be done is to eliminate “the obstacles that hold back growth” by “facilitating balance sheet repair and implementing structural reforms.”

An important implication of Borio’s analysis, in the case of average inflation targeting, is the procyclical risk of a policy that raises inflation above its long‐run target only during expansions. If the result is more severe busts, the paradoxical end result could be that we get stuck at the ZLB more rather than less often (see Selgin).

Lack of Fundamental Reform

The Fed’s year‐long review of its monetary policy framework may have been publicized on a grand scale, but it is clear that the review was constructed without any interest in fundamental reform. Quite simply, the dual mandate of price stability and maximum employment was taken as given. In effect, the Fed wanted to give the appearance of doing something useful without committing itself to something that would allow critics to say it had failed later.

With regard to the “maximum employment” mandate, the Fed has never tried to establish a definite numerical value. To its credit, the Fed realizes that, in the long run, the natural rate of unemployment is determined by market forces—not monetary pump priming. As Fed Vice Chairman Richard Clarida stated, in commenting on the newly amended Consensus Statement:

First and foremost, our policy framework and strategy remain focused exclusively on meeting the dual mandate assigned to us by the Congress. Second, our statement continues to note that the maximum level of employment that we are mandated to achieve is not directly measurable and changes over time for reasons unrelated to monetary policy. Hence, we continue not to specify a numerical goal for our employment objective as we do for inflation. Third, we continue to state that an inflation rate of 2 percent over the longer run is most consistent with our mandate to promote both maximum employment and price stability.

A careful examination of the Fed’s performance since 1913, when the Federal Reserve Act was passed, is long overdue. Along with such a review, it would be useful to also consider the case for a rules‐based monetary regime as opposed to a purely discretionary monetary framework. There are many monetary rules—ranging from a commodity standard to a demand rule (also known as a nominal GDP targeting regime) to a private, free‐banking regime. Since a demand rule is becoming increasingly popular, I will briefly summarize it.

The Case for a Demand Rule

While there is a case for the Fed to move to a price‐level target and end inflation targeting, there is also a case for getting rid of the dual mandate and moving to a single mandate—namely, achieving a stable path for nominal income. In calling for a “demand rule,” William Niskanen observed:

It is important to recognize that a demand rule is consistent with any desired price‐level path, including a stable price level. My primary point is that a demand rule is potentially superior to a price rule, whatever the desired price‐level path, because of the different response to changes in supply conditions. A central bank following a demand rule would not respond to either positive or negative supply shocks; such shocks would lead to a one‐time change in the combination of price and output changes in that year, but would not lead to a long‐term change in the inflation rate. A central bank following a price rule, in contrast, would increase the monetary base in response to a positive supply shock and would tighten the base in response to a negative shock, thereby increasing the variance of output. Similarly, a demand rule is potentially superior to a money‐supply rule because it accommodates unexpected changes in the demand for money. The general case for a demand rule, thus, is that it minimizes the variance in output in response to unexpected changes in either supply or demand.

One version of a demand rule is to use nominal GDP level targeting, in which the Fed makes up for misses in its desired long‐run level growth target. For example, if the target is 5 percent and NGDP growth fell below that target, the Fed would allow NGDP to grow by more than 5 percent until the level growth path was once again reached (see Sumner, Beckworth, and Selgin). Alan Greenspan is thought to have implicitly adopted a demand rule from early 1992 through the first part of 1998, during the so‐called Great Moderation (see Niskanen). The Fed could use QE to offset declines in the velocity of money so that the quantity demanded and supplied of money meshed. Over time, the path of total spending would be more predictable and limited than under average inflation targeting. However, an objection to NDGP targeting is that it introduces slippage between policy actions and long‐term price stability. The tradeoff is that an NGDP target gives you desirable spending fluctuations but more slippage, relative to what a price‐level target could deliver.

Reacting to the Pandemic

The lockdown of the U.S. economy, in response to COVID-19, produced a major negative supply shock that put a sudden brake on what had been a robust job market. Unlike the Great Depression, which was initiated by a sharp fall in the money supply, the current recession was initiated by the government lockdown of the economy in response to COVID-19. The rate of spending declined precipitously as the velocity of money took a free fall (Figure 3), reflecting the strong demand for money balances and the increase in uncertainty. Nominal GDP, which had been growing at about 5 percent before the pandemic, went sharply negative (Figure 4). The Fed’s response was to lower its policy rate to the ZLB (0–25 basis points), engage in open‐ended LSAP, and use its emergency lending powers to supply liquidity to financial markets.

Note: M2 velocity is the ratio of quarterly nominal GDP to the quarterly average of the M2 money stock. Source: St. Louis Fed, FRED

Source: St. Louis Fed, FRED

At near‐zero interest rates, and under the influence of the Fed’s promise to keep rates low for the foreseeable future, asset prices have performed well even as the economy has languished. The Fed’s move to average inflation targeting is intended to provide further assurance that the Fed will keep rates lower for longer, thus supporting financial markets, encouraging leverage, and subsidizing risk. The hope is that average inflation targeting will push inflation above 2 percent, reduce real interest rates, and stimulate consumption and investment. However, there are risks involved. Keeping rates artificially low could further inflate asset prices, distort the allocation of capital, lower productivity, and increase debt. Eventually, the Fed’s pseudo wealth effect would be revealed as the financial boom became a bust.

Moving to an NGDP level target would improve the monetary policy framework, but even that rule is constrained by the Fed’s floor system and the payment of interest on excess reserves (IOER).[1] Abolishing IOER (while retaining interest on legal reserves) would improve the monetary transmission mechanism, so that changes in base money could have a greater impact on nominal income. Rather than expand the Fed’s responsibility into unchartered waters via fiscal QE (Selgin), ending the dual mandate and focusing on stabilizing long‐run nominal income growth would help reduce the uncertainty inherent in a purely discretionary central bank, with a drift toward inflation and fiscal QE.

The Fed recognizes that the Phillips curve is a poor policy guide and that the natural rate of unemployment is ultimately determined by markets. However, in order to satisfy Congress, the Fed must act as if it has greater control over real variables than it actually does. Thus, while the Fed is hesitant to claim that it can give an accurate numerical value to its “maximum employment” mandate, Chairman Powell is not shy in proclaiming: “In conducting monetary policy, we will remain highly focused on fostering as strong a labor market as possible for the benefit of all Americans.”

As an agent, the Fed must abide by congressional mandates. The Fed is therefore constrained in considering fundamental reform in its review of the monetary framework. Congress must initiate major changes in the monetary regime, but is reluctant to do so, especially in light of its incentive to have the Fed monetize debt, keep rates low, and engage in fiscal QE. There have been calls for establishing a commission to carefully examine the Fed’s monetary performance over more than a century, but nothing has been done. Instead of having the Fed review its “strategy, tools, and communication practices” every five years, as recommended by the FOMC, it is time for Congress to step up to the plate and not only examine the Fed’s performance but discuss alternatives to the current dual mandate. Considering NGDP targeting is only one possible rules‐based alternative.

Conclusion

Under the current monetary regime, the size of the Fed’s balance sheet no longer reflects the stance of monetary policy (see Plosser). Unconventional monetary policy has increased the Fed’s balance sheet from less than $900 billion before the 2008 financial crisis to more than $7 trillion today. The Fed held its policy rate near zero for 7 years, from 2008 to 2015, and it is now back to zero—and plans to stay there. Instead of adhering to its “price stability” mandate, the Fed has drifted into accepting 2 percent inflation as the norm, and now is committed to average inflation targeting.

The Fed’s message that rates will stay near zero for a long time—and that inflation will be allowed to exceed 2 percent to make up for past misses—is meant to increase inflation expectations. But, if the Fed’s primary mandate is long‐run price stability, should it be the job of the Fed to spike inflation?

Average inflation targeting is the result of a superficial review of the Fed’s framework. All it does is increase the scope for monetary discretion. The vagueness in “average” makes it even harder to show that the Fed has failed, again, like an unfalsifiable “scientific” claim.

Americans should be entitled to a more substantial review that also calls into question the very foundation of the Fed’s operations. Such a review should consider alternative monetary frameworks, including NGDP targeting.

[1] The Fed’s post‐2008 operating framework—the so‐called floor system—is an important part of the monetary framework. Inflation has been avoided (so far) by the Fed’s payment of interest on excess reserves (IOER), which discourages new base money from being lent out and influencing nominal income. Under the floor system, the IOER rate becomes the key policy rate and is set administratively by the Board of Governors. This arrangement differs substantially from the pre‐2008 operating system in which the FOMC set a target rate for the federal funds rate and then supplied the reserves needed to meet demand at that rate. Under the current system, the demand for reserves becomes perfectly elastic (flat) at the IOER, and small movements in the supply of reserves have no effect on the fed funds rate (see Ihrig, Meade, and Weinbach; also Selgin).

[Cross‐posted from Alt-M.org]

This article first appeared at the Cato Institute.

Image: Reuters.