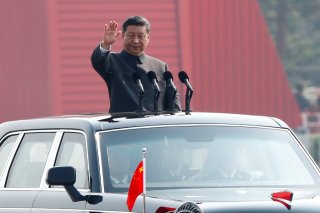

Imperial Overstretch: Has Xi Jinping’s China Gone Too Far?

Abandoning the path of development taken by Deng Xiaoping, Xi Jingping has overextended China economically, militarily, and politically.

If Deng Xiaoping were alive today, he would neither be pleased nor surprised. The pro-market reforms that launched China into a global power are being undone under Xi Jinping, curtailing growth for the sake of concentrating political power, spending far too much political capital on crushing dissent and punishing the last vestiges of democratic ambitions, and overextending China militarily in the Indo-Pacific.

Deng’s critical reforms were based on two fundamental beliefs, first, that communism in China could be saved by creating a vibrant economy and improving people’s lives, and second, without the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in charge, China would descend into chaos. When Wei Jingsheng went on trial in 1979 on charges of being a counter-revolutionary, the first sign was visible that the gaps between economic and political reform and the need for a Fifth Modernization, democracy, would not and could not be resolved.

Under Xi’s leadership, these gaps have turned into a chasm. His selection as president in 2013 was a transformative event. While Mao Zedong unified the nation and Deng made it rich, Xi has created an overbearing surveillance state marked by sharpened authoritarianism. So-called “wolf warrior diplomacy,” which is assertive, confrontational, and hypersensitive to criticism, has become the hallmark of Chinese diplomacy. China is projecting power through the most ambitious and expensive construction project in human history. Xi’s policies envision a new world order with Beijing at the center. This is oddly a bastardized return to traditional pre-modern hierarchies based on kowtow, which ritualized inequality among states and recognized the moral superiority of China.

However, in autocracies like China’s, there is often a fatal flaw. Chinese leaders have painted themselves into a corner by not embracing diversity of opinion and by failing to admit when they make mistakes. An apt analogy is the recent Covid-19 lockdown in Shanghai. To control the spread of the virus, China locked down the city of 25 million but in so doing created lasting damage to its economy while harming the livelihoods and psychosocial well-being of its residents. China’s overreach led to a rare outpouring of dissent.

Xi has stressed that CCP leadership and the “advantages of the socialist system” are the cure for all problems, but challenges keep piling up. China’s economy is slowing, local debts are increasing, and its corporations have borrowed with reckless abandon. Trumpeting that only the CCP can solve mounting social and economic problems is dangerous since it raises the risk of over-promising and under-delivering. During the 1980s, there were criticisms of Deng’s reforms. The absence of any dissenting voices riled not just university students but workers as well. The inability of a tone-deaf CCP leadership to listen to criticism directly led to the Tiananmen movement.

China’s imperial overreach, a combination of inflexible leadership, a failure to admit mistakes, and intolerance of criticism is alive and well.

China is experiencing pain in its economy that it hasn’t felt in decades. A zero-tolerance policy on Covid-19, as well as a regulatory crackdown on the tech sector and the real estate industry, have left China’s labor market in a precarious state. Beijing reported an urban employment figure of more than 5 percent, but the devil is in the details. Migrants from rural areas aren’t working in urban areas because of changes in the labor market, including having to be in quarantine. For example, the number of rural laborers working in major metropolitan areas declined by 5.2 million workers in 2020, or 1.8 percent due to Covid-19 restrictions. There’s scant evidence they are going to return and this will cause significant damage to the economy. Some of the jobs previously held by migrants aren’t coming back due to declines in manufacturing and increased automation. As China now struggles with a labor shortage, it looks to automation to solve some of its critical manufacturing challenges.

But the Chinese Communist Party cannot get out of its own way. A regulatory crackdown on private enterprise has left tens of thousands of people out of work in the critically important tech sector. The move to better regulate private enterprise and disrupt monopolies comes with little explanation and is a departure from the past, where a hands-off approach led to a surge in growth evidenced by the success of e-commerce giant Alibaba, as well as Huawei and Tencent. China’s overreach has held back its economic engine to the tune of $1.5 trillion and has been personified by the silencing of billionaire Jack Ma. In 2020, when Ma in 2020 spoke at a conference against the actions of Chinese state-owned banks, regulators brought him in for questioning and halted the IPO of Alibaba subsidiary Ant Group. Since then, the private sector crackdown has spread across industries related to education, cryptocurrencies, and finance.

The motivations behind Xi Jinping’s economic crackdown point to a desire to consolidate his political power ahead of the 20th Party Congress, which is scheduled for later this year. The “common prosperity” rhetoric designed to shift the narrative to closing income gaps between China’s richest and its most beleaguered masses feels like a secondary effort that will do little to address institutionalized inequalities and corruption.

Hong Kong also personifies Xi’s overreach. The recent arrest of ninety-year-old Cardinal Joseph Zen, a democracy and human rights activist, provides valuable insight. To outsiders, the arrest of an elderly man is a testament to how petty Chinese enforcement of its 2020 national security law has become, because after all, what national security threat does an elderly retired Catholic cleric pose to China? The arrest of pro-democracy activists, opposition lawmakers, and a crackdown on political expression has been brutal. Now, the potential of a crackdown on religious freedom makes Chinese overreach another step beyond the pale. Zen’s arrest exemplifies Xi’s intolerance of pluralism where other ideas, including democratic ones, might exist alongside his own.

Hong Kong’s Western-influenced political and cultural norms and values have been all but dismantled since the national security law took effect. While Hong Kong’s “zero Covid” policy has contributed to the largest brain drain in the city’s history, some of the vast relocations of expats and residents are also linked to the draconian security law. Its passage also accelerated the growth of Hong Kong’s diaspora which numbers in the hundreds of thousands. Even now, while safe across oceans or international borders, Beijing holds potential leverage over those who speak out and have family or financial assets remaining in Hong Kong.

China’s relentless pursuit of growth and a dogged insistence on reclaiming the hierarchies that existed prior to its Century of Humiliation at the hands of the West have harmed its international reputation. One does not need to look far to find examples. The Mekong River originates in China but flows down into lower basin countries such as Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam. To satisfy its vast energy demands, China built the Manwan Dam in 1995 and has since built ten more. Eleven more dams are in different stages of construction in Laos and Cambodia.

The Mekong River is host to 20 percent of the world’s freshwater fish and is a critical economic resource for people in the region. However, China has used upstream dams as leverage against downstream countries. Even though evidence, such as that provided by the Mekong Dam Monitor, shows that Chinese dams are damaging the environment around the Mekong, China is resistant to help. Rather than provide information to downstream countries about potential changes in the flow of the river, China has largely refused to share valuable data.

Since its inception, the discourse surrounding the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has been vociferous and wide-ranging. There are multiple dimensions, but aside from the trade and strategic ramifications, financing has always been a major concern. The BRI is not a Chinese-style Marshall Plan done largely through grants; Chinese investors expect to make a profit. According to AidData, policymakers in low and middle-income countries are mothballing high-profile projects because of overpricing, corruption, and debt sustainability concerns. Malaysia is a prime example. Instead of creating meaningful coalitions, the BRI has exposed China’s shortcomings, which ignore critical measures like monitoring and evaluation.

China’s promise of a peaceful rise has instead taken on an aggressive military dimension, threatening the entire Indo-Pacific region. China’s maritime ambitions and buildup of a blue water navy pits it not only against its Southeast Asian and East Asian neighbors but also against the United States. Moreover, claims related to the nine-dash line or an exclusive East China Sea Air Defense Identification Zone place it in opposition to international norms governing both freedom of the sea and navigation. Additionally, speculation over whether China’s heightened rhetoric and enhanced weapons capability regarding an invasion of Taiwan have increased fears of an outcome that would be nothing less than catastrophic.

The rise of China as a world power has been an epic event. Its promise of being an integral part of the international system was heralded and encouraged, but the question of whether Xi Jinping and the CCP understand the dangers of overreach will determine whether shared prosperity will be realized. For China, real genius is knowing when and where to stop.

Mark S. Cogan is an associate professor of peace and conflict studies at Kansai Gaidai University based in Osaka, Japan and a former communications specialist with the United Nations.

Paul Scott is a Japan-China specialist and democracy activist who is currently teaching in the Graduate Program in Peace and Conflict Studies at the Universitat Jaume I, Castellón de la Plana, España and at the Catholic University of Lille, France.

Image: Reuters.