Beware Collusion of China, Russia

Mini Teaser: U.S. policies have created a risk of pushing two great powers together.

VISITING MOSCOW during his first international trip as China’s new president in March, Xi Jinping told his counterpart, Vladimir Putin, that Beijing and Moscow should “resolutely support each other in efforts to protect national sovereignty, security and development interests.” He also promised to “closely coordinate in international regional affairs.” Putin reciprocated by saying that “the strategic partnership between us is of great importance on both a bilateral and global scale.” While the two leaders’ summit rhetoric may have outpaced reality in some areas, Americans should carefully assess the Chinese-Russian relationship, its implications for the United States and our options in responding.

VISITING MOSCOW during his first international trip as China’s new president in March, Xi Jinping told his counterpart, Vladimir Putin, that Beijing and Moscow should “resolutely support each other in efforts to protect national sovereignty, security and development interests.” He also promised to “closely coordinate in international regional affairs.” Putin reciprocated by saying that “the strategic partnership between us is of great importance on both a bilateral and global scale.” While the two leaders’ summit rhetoric may have outpaced reality in some areas, Americans should carefully assess the Chinese-Russian relationship, its implications for the United States and our options in responding.

The Putin-Xi summit received little attention in official Washington circles or the media, and this oversight could be costly. Today Moscow and Beijing have room for maneuver and a foundation for mutual cooperation that could damage American interests.

Specifically, the two nations could opt for one of two possible new courses. One would be to pursue an informal alliance to counter U.S. power, which they see as threatening their vital interests. This path might prove difficult, given competing interests that have burdened relations between Russia and China in the past. Still, stranger things have happened in history between two nations that confront similar challenges. But there is a second possibility. They could play a game of triangular diplomacy similar to the Nixon/Kissinger strategy of the 1970s. In this scenario, Moscow and Beijing could dangle the prospect of a potential alliance or ad hoc cooperative arrangement with the other to gain leverage over Washington and put the United States at a bargaining and power disadvantage.

So far, Russian-Chinese ties appear in large part to be an unintended consequence of American policies aimed at other objectives. Thinking about unintended consequences in foreign policy has never come easily to U.S. policy makers, particularly since the end of the Cold War, when the pursuit of democratic and humanitarian triumphalism has virtually become a form of political correctness among both Republicans and Democrats. Though the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan eventually produced a modest degree of soul-searching, the excitement of the Arab Spring—and the external pressure of the interventionist impulses of Britain and France in particular in Libya and Syria—seems to have cut short this much-needed introspection about what works and what doesn’t in U.S. foreign policy.

It is ironic that some European countries that are unable to pursue minimally sound economic policies, or to effectively integrate exploding immigrant populations, have developed the irresistible temptation to promote Europe as a model for the rest of the world—if, of course, the United States supplies the muscle. Taking into account their own history, it is especially curious that these Europeans should not recognize the increasingly apparent reemergence globally of traditional power politics at the expense of their social-engineering vision of peace through democracy.

In fact, the future in many ways now resembles the past, with competing power centers and clashing values. As historian Christopher Clark writes in his magisterial work on the origins of World War I, “Since the end of the Cold War, a system of global bipolar stability has made way for a more complex and unpredictable array of forces, including declining empires and rising powers—a state of affairs that invites comparison with the Europe of 1914.” While his stark comparison may seem excessive, there is reason for concern that the current multipolar confusion could once again evolve into two loose alliances or ad hoc alignments increasingly at odds with one another.

AMERICA’S CONVENTIONAL wisdom virtually dismisses the possibility of a global realignment set in motion by China and Russia, which feel threatened by American and European policies and by having to function in the world’s Western-made system. And, whatever the likelihood of a lasting alliance between the two based on their particular strategic interests and values, even a temporary tactical arrangement could have a huge and lasting impact on global politics. Remember the short-lived Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, which in less than two years had dramatic consequences for the world on the eve of World War II. Hardly anyone in London or Paris could conceive of such a diplomatic development.

True enough, much stands in the way of a genuine Chinese-Russian alliance: a history of mutual mistrust; the combination of China’s sense of superiority and Russia’s imperial nostalgia; China’s declining need for Russian technology, including military hardware; Russia’s wariness of substantial Chinese investment in Siberia’s energy development; and the fact that in the long run, China and Russia alike need more from the United States and the European Union than from each other.

Nevertheless, Chinese and Russian leaders will measure these very important differences against fundamental interests that Beijing and Moscow have in common. First and foremost, both face challenges to the very legitimacy of their rule as well as serious challenges from restless ethnic and religious minorities. Accordingly, they are highly sensitive to outside influence in their political systems. And make no mistake, what U.S. and European politicians consider noble efforts to promote freedom and democracy look like hostile efforts at regime change to Chinese and Russian leaders. Foreign guidance on governance to countries with different histories, traditions and circumstances is rarely welcomed, particularly by proud major powers.

Second, despite the fact that Russia’s leaders played a critical part in destroying the Soviet Union, the West generally has treated Russia as heir to the USSR’s policies and objectives. Thus did NATO expand to incorporate not only the former Warsaw Pact but also the three Baltic states. And it has declared its intent to admit Ukraine and Georgia. More broadly, in almost every dispute between Russia and other former Soviet states, even with the authoritarian and repressive Belarus, the United States and the European Union have sided with Moscow’s opponents. This creates an impression that the West’s top priorities, long after the Cold War, include not merely containing Russia but also transforming it.

Similarly, the United States has supported China’s neighbors in nearly all disputes with that country, including territorial disputes. This is not only the case with respect to traditional U.S. allies, such as Japan and the Philippines, but also with Vietnam, which is no more democratic than China and represents a painful episode in American history. The Obama administration’s pivot, while weak on substance, has contributed to China’s narrative of encirclement. From an American standpoint, these moves make sense, and many Asian nations welcome the pivot. But Beijing predictably sees it as a threat. Thus, it isn’t surprising that during President Barack Obama’s recent two-day summit with Xi Jinping at Rancho Mirage, California, the Chinese leader kept the atmospherics positive but evaded any concessions on major issues currently separating the two countries.

China and Russia want to break out of what appears to many in both countries as a new “dual containment” policy, and they also wish to reshape a global political and economic system they see as created by and for the United States and the West to their own benefit. Russian and Chinese leaders instantly see their nations disadvantaged when they hear that they should be “responsible stakeholders” in supporting decisions made in Washington and Brussels, when they see the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund operating largely as instruments of Western policy, and when they experience the United States and the European Union regularly orchestrating the international financial system to advance their own interests. More important, all this stimulates a desire to reshape the global rules to accommodate their power and their aspirations. A number of emerging regional powers seem to share these sentiments.

No wonder leading Russian commentator Andranik Migranyan asks rhetorically whether, notwithstanding many common Russian and U.S. interests, there might be “a greater convergence in Russian and Chinese interests on the matter of containing Washington’s arrogant and unilateral foreign policy that attempts to dominate the world.”

Similar concerns are seen in Beijing and Moscow when the United States pushes them on hot-button issues such as Syria, Iran and North Korea. Certainly, pushing is the right course for Washington. The United States needs their help on these matters, and China and Russia do have their own worries about these countries. But those worries are not necessarily equal to America’s, and they have other important priorities to consider. Accordingly, they don’t feel comfortable being yoked to American interests, especially when they don’t see much effort by Washington to engage in genuine give-and-take or to significantly accommodate their interests in these troubled lands.

Many in Washington seem to believe that notwithstanding the frustrations and ambitions of Chinese and Russian decision makers, they inevitably will wish to avoid rocking the boat in their relations with the United States and the European Union. The European Union is China’s number-one trading partner, while the United States is number two—and Russia comes in at number nine. Likewise, the European Union is Russia’s top trade partner, with China a distant second. The United States is number four on Russia’s list, after Ukraine. China and Russia also have a huge stake in the stability of the euro and particularly the dollar, since a large share of their central-bank reserves is held in these currencies. And China’s holdings of U.S. debt give Beijing a big interest in America’s fiscal solvency.

Despite these close economic ties, however, history demonstrates that economic interdependence only goes so far in preventing international conflict. Indeed, U.S.-Japanese economic interdependence actually contributed to tensions before World War II. Likewise, before World War I, Britain and Germany were each other’s top trading partners. Russia and Germany were economically intertwined before they went to war against each other in 1914—and also before Germany’s invasion of the USSR in June 1941. The decisions to go to war in these cases clearly demonstrate that economic interests may be quickly subordinated to national-security concerns and domestic political priorities when disagreements reach the boiling point.

This is why it is a mistake to assume that Washington or Brussels can essentially continue to set the global agenda and decide upon international actions. China and Russia alike agree with the United States and the European Union that it would be better to see Iran and North Korea without nuclear weapons and to avoid Taliban rule in Afghanistan. From Moscow’s perspective as well as Beijing’s, however, these mutual interests are secondary when set against their efforts to retain influence in Central Asia or East Asia and particularly their desire for stability at home.

LOOKING TO the future, we cannot know the precise consequences of a Sino-Russian alliance if one should emerge. Among other factors, the results would depend on the durability of the arrangement, the strength of the conflicting interests pushing Beijing and Moscow apart, and the magnitude of the pressure from the United States and its allies pushing them closer together. Nevertheless, the Cold War was not so long ago that Americans cannot envision a polarized world, with increasing diplomatic stalemate or worse.

Regarding Iran, imagine if China and Russia offered Tehran security guarantees or promised to rebuild its nuclear infrastructure after a U.S. or Israeli attack. In Syria, we already see the results of having Russia on the other side and China sitting on the fence. Or imagine Chinese support for guerrillas in the Philippines or Kremlin encouragement of Russian-speaking minorities in Latvia and Estonia. If U.S. relations with Russia and China sour, these nightmares can’t be excluded.

Russia and particularly China already are steadily increasing and modernizing their military capabilities. For now, Washington is responding with caution to avoid the appearance of overreacting. But picture what might happen if those militaries continue to grow and maneuver worldwide, especially in cooperation with each other. It isn’t that war would become likely between the West and these other superpowers. But tensions and conflicts could grow; hot spots could further fester, à la Syria. Great-power animosities would seriously complicate international efforts at crisis management. This all would make international life that much more uncomfortable, if not also dangerous. It certainly would create a specter of miscalculation, escalatory pressure and sense of crisis. And there would be nasty consequences for U.S. prospects for prosperity.

A world of a Sino-Russian alliance or even triangular diplomatic games is certainly not inevitable. But it is a risk the West must be much more aware of. Moreover, making it less likely does not require surrender or appeasement. The United States, Europe, Japan, South Korea, and numerous other allies and friends around the world have enough power and leverage to discourage leaders in Beijing or Moscow who might set aside their own conflicts and seek to disadvantage the United States and the West. But a tough-minded yet prudent American foreign policy based on the world as it actually is would realistically evaluate the interests of other powers and take them into account in order to reduce the risk of provoking a counterbalancing global coalition. Thus, U.S. foreign policy should pay more attention to the benefits of working with Russia and China and taking into account their fundamental interests. Obviously, U.S. leaders must stand their ground on matters of national concern. But more cooperation with Russia and China should be on their minds. Such cooperation is not a reward for good behavior. It’s the best and perhaps the only way to defuse crises and reduce international stalemate; it is also a fundamental U.S. national interest.

Leslie H. Gelb is president emeritus of the Council on Foreign Relations, a former senior official in the State and Defense Departments, and a former New York Times columnist. He is also a member of The National Interest’s Advisory Council. Dimitri K. Simes is president of the Center for the National Interest and publisher of The National Interest.

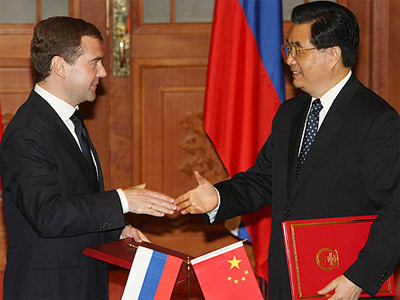

Image: Wikimedia Commons/kremlin.ru. CC BY 3.0.

Image: Pullquote: Make no mistake, what U.S. and European politicians consider noble efforts to promote freedom and democracy look like hostile efforts at regime change to Chinese and Russian leaders.Essay Types: Essay

Pullquote: Make no mistake, what U.S. and European politicians consider noble efforts to promote freedom and democracy look like hostile efforts at regime change to Chinese and Russian leaders.Essay Types: Essay