Pariahs in Tehran

Mini Teaser: We shouldn't believe all we hear about the success of Obama's Iran strategy. The world needs to put a stranglehold on Tehran.

THE MOST interesting thing about the Obama administration’s Iran policy is that it is working, but it probably isn’t going to work.

THE MOST interesting thing about the Obama administration’s Iran policy is that it is working, but it probably isn’t going to work.

The United States has achieved some truly remarkable feats in pursuit of the White House’s Iran policy over the course of the past twelve months, achievements many critics from left, right and center all thought impossible. With perseverance and perspicacity, and some help from the stupidity of the Islamic Republic’s leadership, Washington has secured widespread backing in Europe, East Asia and the Middle East for imposing various new sanctions on the country.

Of greatest importance, in June 2010 the administration secured the passage of a new UN Security Council resolution (number 1929) that imposed a fourth round of sanctions on Tehran for its failure to comply with its obligations to the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) and its failure to cease its nuclear-enrichment activities. In concert with France, Britain and Germany (and some quiet help from Israel, Saudi Arabia and the UAE), the United States convinced both Russia and China to agree to the new resolution as well. Resolution 1929 bans arms sales to Tehran, something most thought unthinkable given the Russian and Chinese ardor to continue profiting from that market. It also included language that enabled member states to impose harsh new financial controls and limits on investment in the Iranian energy sector.

The Russians have even gone so far as to privately convince their own oil giant, Lukoil, to stop selling gasoline to Iran. The Europeans have likewise pushed Shell and a variety of other major firms on the Continent to reduce their purchases of Iranian oil, and major European banks and businesses are shutting down their operations in the Islamic Republic. The new sanctions, both those contained in the resolution itself and those enacted by member states (particularly the EU, Japan and South Korea) in conformity with the provisions of the resolution, go far beyond what most believed possible. They truly are harsh measures, something U.S. officials had hoped for and threatened, but in private had doubted would be diplomatically feasible. And they have gotten Tehran’s attention, with no less a figure than former-President Ayatollah Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani warning his countrymen that the sanctions are no joke and that the country’s situation is dire.

Indeed, since the passage of the UNSCR, the Iranian regime has been broadcasting on all frequencies, overt and covert, that it is ready to talk seriously with Washington about its nuclear program. For this reason, it seems likely that the United States, along with Britain, France, Russia, China and Germany (the P5+1), will sit down with Iranian representatives before the end of this year for formal negotiations. It is also likely that Iran will offer to discuss reprocessing its low-enriched uranium (LEU) to refuel the Tehran Research Reactor, something it already agreed to in a deal brokered by Brazil and Turkey in an eleventh-hour effort to stave off the UN sanctions vote. The Iranians are reportedly hinting that such an agreement with the P5+1 could lead to further deal making over its nuclear program more generally.

All of this constitutes a tremendous turnaround from Bush 43. It’s not surprising that the White House would want to believe that its successes will pay off, compelling Tehran to bow to international pressure and agree to a deal on its nuclear program in toto.

But just because the administration’s critics have been wrong, does not mean that they will be wrong.

THE PROBLEM with Washington’s current approach is that it is intended to put intense-enough pressure on Tehran that the government will negotiate a halt (or even a rollback) of its current nuclear program. It is a reasonable position—one I proposed back in 2004 and staunchly supported up until Iran’s disputed presidential election on June 12, 2009. But it is no longer enough.

June 12, 2009, and the weeks that followed were a watershed for the Islamic Republic. The regime confronted its most dangerous internal threat ever as millions of Iranians took to the streets and to their rooftops to protest what they believed was a stolen election. For the first time, they demanded the resignation of Iranian Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. In effect, they demanded an end to the Islamic Republic itself.

At that moment, the more moderate voices within the Iranian establishment counseled making concessions to the opposition. These were the leaders of the Iranian reform movement and, not coincidentally, the same people who had shown a willingness to negotiate with the West in the hope of alleviating Iran’s crippling economic and diplomatic problems—from unemployment to declining oil revenues to rampant corruption. However, Tehran’s hard-liners, particularly the leadership of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, insisted on cracking down on the opposition instead. So too did the supreme leader, who apparently believes that the shah fell because he was weak, having compromised with the revolutionaries (including himself). The ayatollah sees those very concessions as the beginning of the end of the shah’s rule. Neither Khamenei nor the Revolutionary Guard, nor any of Iran’s other hard-line leadership, plans to be ousted the way that the shah was, and they have made clear that they will employ whatever levels of violence are necessary to retain power.

In the weeks and months that followed, the regime embarked on a massive, systematic and brutal, but also highly sophisticated, crackdown that for all intents and purposes crushed the street protests of the opposition Green movement. Simultaneously, the regime’s hard-liners effectively “purged” the government’s more moderate elements. Some were imprisoned; most were simply left in place but deprived of power—which in Iran’s Byzantine system of personal politics derives largely from informal influence ultimately bestowed by the supreme leader himself.

Thus, today, Tehran’s hard-liners dominate Iranian decision making in ways that they have not since the early 1980s. Of course, there are still fissures even within these innermost circles—it is Iran after all. However, the problem for the Obama administration is that Iran’s hard-liners have shown absolute consensus in consistently maintaining that Iran needs, and is entitled to, its nuclear program. Some have gone so far as to question the utility of Iran remaining part of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT); some have openly supported the acquisition of nuclear weapons. Ayatollah Muhammad Taqi Mesbah-Yazdi, a member of the Assembly of Experts and an important adviser to President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, wrote that Tehran “must” produce nuclear weapons even if Iran’s “enemies” don’t like it.

What’s more, the hard-liners overwhelmingly neither want nor care about having a better relationship with the United States. President Ahmadinejad is the exception that proves the rule: alone among the hard-liners, he has called for negotiations with the Americans, but only to demonstrate that Iran is so powerful and important that it must be seen as an equal by the United States. Ahmadinejad has been fiercely opposed by the rest of the Islamic Republic’s hard-line establishment, including (as best we can tell) by Khamenei himself.

Ultimately, Tehran’s hard-liners insist that Iran is strong enough to withstand and outlast any sanctions that might be imposed upon it, and they are certain that everyone else will realize that the world needs Iran more than Iran needs the rest of the world. Certainly, they might ultimately change their minds. Muammar el-Qaddafi once believed much the same about Libya. He eventually figured out that he was mistaken, and he was forced to give up his own nuclear program and make amends with the United States and the international community. But even that took ten years, and Iran is a lot bigger and a lot richer than Libya—a point that Tehran’s hard-liners regularly recite.

As Iran scholar Ray Takeyh nicely summarized the problem:

The essence of Washington’s approach is that confronted with a choice of debilitating isolation or rejoining the community of nations, Iran will eventually make the “right” decision. The Islamic Republic, however, is too wedded to its ideological verities and too subsumed by its rivalries to engage in such judicious determinations.

So even if the Obama administration is able to build a sanctions regime as harsh as that imposed on Libya, we should not assume that it is going to succeed—be it in months or in years. Given Iran’s size, oil wealth, internal paralysis, and ideological and nationalist stubbornness, history suggests it is going to take a long time to work—if it ever will.

OF COURSE, the catch is that unless and until the sanctions succeed, Iran’s nuclear program will keep plugging along. Within a few years, Iran is likely to have the capability to produce nuclear weapons and, should the regime so desire, could deploy a full-blown arsenal soon after.

This is why a growing number of Americans want to give up on pressure and persuasion altogether and instead just bomb Iran’s nuclear program. It’s easy to empathize with the fear and frustration that drives smart, patriotic people to embrace air strikes as a means of eradicating the potential threat from Iran’s nuclear program. It is not an option I would rule out unequivocally, but it is an option with a great many flaws.

It is worth starting any discussion of the military option by recognizing that, unless Tehran does something stupidly belligerent, the United States will not have any standing in terms of international law (or international opinion) to mount such an attack. All of the UNSC resolutions against the Iranian nuclear program have very clearly stipulated that they do NOT authorize the use of force. This reflects the Russian, Chinese and scores of other countries’ deep and widespread animosity toward a military solution. Any unprovoked American attack on Iran is likely to be harshly condemned across the globe.

Perhaps even more importantly, it is likely to be condemned by ordinary Iranians. Many advocates of air strikes argue that they would help turn the people against the regime, as the population would blame the leadership for bringing this calamity down upon them. This is obviously possible, but there really isn’t much evidence to support the idea. In fact, the vast majority of the evidence, both from Iran and from other historical cases, points in the opposite direction. Iranians are highly nationalistic, and past aggression—from the Iraqi invasion of 1980 to the Taliban’s killing of eight Iranian diplomats in 1998—has typically engendered a powerful “rally ’round the flag” effect, regardless of who is in power. Likewise, in most cases of strategic bombardment, or even just more limited air strikes, the people getting bombed have tended to blame their attackers, not their leaders.

This means that an American air campaign would probably strengthen popular support for the current leadership—exactly the effect we should hope to avoid. It will also provide those in power with the opportunity to crack down even more on the opposition, pushing any change in regime even further into the future.

Moreover, a different group of leaders might decide that having once been attacked for pursuing nuclear enrichment, the smart thing would be to give up this effort. But Iran’s hard-liners are not the kind to reach that conclusion. They are mostly motivated by fear and hatred of the United States, consistently favoring belligerence over acquiescence. What’s more, many of the hard-liners seem to want nuclear weapons to deter just such a strike. Consequently, the best bet is that in the wake of a bombing, the regime will redouble its efforts to acquire a nuclear deterrent to prevent Washington from being able to bully Tehran again.

As well, an unprovoked American attack will likely mean the end of the international effort to contain the Iranian nuclear program altogether. Tehran will probably withdraw from the NPT, arguing (rightly) that the vast majority of the information that the United States relied on to mount the air strikes came from the IAEA inspectors—and since the NPT was a vehicle for American aggression against Iran, there is no reason for Tehran to remain a party to it. As for the international community, they will doubtless blame Washington for having driven the Iranians out of the treaty. Gone too will be the international consensus to compel Iran to end its nuclear activities through sanctions. America would have violated a critical provision of the resolutions, not to mention the UN Charter, and will have to expect that China will lead a stampede of countries away from that effort and back into the arms of the Islamic Republic.

A repeat attempt by the United States (or anyone else) to destroy Iran’s facilities by force will then be impossible. Once the IAEA inspectors are gone, so too will be our best and most comprehensive sources of information on the Iranian program. Washington won’t have the option of bombing Iran again if the regime begins to rebuild its nuclear capabilities after the first round of strikes. And serious international pressure on Tehran will come to an end.

Thus, air strikes have to be seen as a “bet everything on one throw of the dice” kind of policy: either they succeed in ending the Iranian program now and forever (which seems extremely implausible), or else they thoroughly undermine all of America’s options to do so—additional military strikes, sanctions, international isolation and everything else. Under current conditions, attacking Iran is more likely to guarantee an Iranian nuclear arsenal than to preclude it.

Nor does the other side of the ledger have much to recommend it. Most American (and Israeli) nuclear experts now think that Tehran is so far along that it could rebuild the entire program and be back to where it is at present in just a year or two. And many already fear that Iran has secret facilities, or is hiding key machinery and material for its nuclear program—then the program wouldn’t be set back much at all by a military campaign.

It is also worth keeping in mind that Iran probably will retaliate against the United States. Again, this isn’t certain, but the evidence indicates that Iran does retaliate whenever it is (or believes it is) attacked. The Islamic Republic has a formidable capacity to employ terrorism and a lot of allies, like Hezbollah and Palestinian Islamic Jihad, who could also cause a great deal of damage on Tehran’s behalf. If there is anyone out there who might be able to replicate a terrorist attack as terrible as 9/11, it is Iran. Tehran can also ramp up its support of Taliban fighters battling U.S. troops in Afghanistan, and it could turn up the heat on American allies in the region, particularly Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Bahrain and Iraq. Now, all of this might be a worthwhile price to pay if the United States could eliminate the threat of an Iranian nuclear program altogether, but given the fairly modest delays that air strikes seem likely to impose—and the damage to U.S. policy in the aftermath—these risks further suggest that the costs of an attack outweigh the benefits.

Once the United States starts a war with Iran—and launching air strikes will be war—it is impossible to know how it will end, and what would be required of Washington to end it. America may well feel compelled to respond to any Iranian retaliation, setting off a tit-for-tat cycle, raising the risk of escalation on both sides. The incredible paranoia and intractability of the Iranian regime has led to repeated instances in which Tehran refused to abandon courses of action even though it was suffering horrific damage—remember the hostage crisis? The Iran-Iraq war? In other words, the same behavior patterns that make it hard for the United States to coerce Iran by sanctions also make it unlikely that Washington can coerce the Islamic Republic by war. As we should have learned in Iraq, wars always entail very significant unforeseen consequences, and we need to recognize that bombing Iran could lead us down unexpected paths to even-worse outcomes (like invading and occupying Iran) to end what we started.

With a country as difficult as Iran, the United States should only launch air strikes if it is ready to pay all of the potential costs—and there are few Americans ready to bear the price of another major U.S. war in the Middle East.

SINCE THE cost-benefit analysis of a military campaign against Iran still does not add up the right way for the United States, a number of Americans have begun to argue that Washington should fall back on deterrence instead. While there is considerable evidence that deterring Tehran could work, many find it an unpalatable option: simply acquiescing to an Iranian nuclear capability—and possibly to an Iranian nuclear arsenal. And the problem with nuclear deterrence is that as robust as it has proven to be, there are no guarantees of success, and failure is invariably catastrophic. For that reason, it would still be far more preferable to convince Iran not to acquire a nuclear-weapons capability in the first place, rather than to allow it to do so and then try to protect American interests without triggering a nuclear exchange.

So what is the right answer? For those concerned that the current approach won’t succeed, but are fearful that air strikes will create more problems than they solve (and are not yet ready to simply accept an Iranian nuclear capability), the best course of action is to go back to the administration’s basic strategy—and put it on steroids.

Pressure is our only recourse. Even intense pressure may not be enough, but it is better than doing nothing, and better than war—and it might even work. Intense pressure on the regime could slow the program further. It could create new stresses and strains in the system. It could create new opportunities for Iran’s moderates, those most interested in reaching an accommodation with the international community. It could even empower the Green movement.

The key is to defeat Tehran’s strategy. Since Iran’s hard-liners believe that they can withstand any pressure from the international community and that eventually that pressure will slacken, America’s best chance is to design a strategy that will ensure that the pressure never lets up, and instead increases steadily over time. If Iran’s situation gets worse and worse, rather than better and better, the United States and its allies may just be able to alter Tehran’s path. It could happen from above: the more pragmatic Iranian power wielders may change course, discrediting the hard-liners along with the rest of the Iranian elite. It could happen from below: the opposition could be strengthened by deepening disaffection, creating bottom-up pressures on the leaders that would frighten them into reversing course. Either way, Iran might finally back down. The question is whether we have the time to enact such a python-like strategy.

There is reason to believe we do. The IAEA has reported that Tehran is having trouble with its centrifuge cascades and has not been rapidly adding new ones to its main enrichment facility at Natanz. Unless there are covert enrichment facilities like the one discovered near Qom last fall up and running without our knowledge, this means that the rate at which the regime is manufacturing LEU has not risen. In addition, at some point in 2009 or early 2010, Iran had enriched enough LEU so that if it wanted to break out of the NPT and build a bomb it could do so. This was something the Israelis feared intensely, calculating that Iran might be able to have a deliverable weapon in as little as a year. Yet once the Iranians crossed that dangerous threshold, they did not mount a crash program to build a bomb. Now, Tehran may ultimately want an arsenal, but this shows that the regime is not simply looking to get its hands on one as quickly as it can.

Indeed, the American intelligence community and most of its foreign counterparts believe that Iran probably won’t field a nuclear arsenal until the middle of the decade. Even Israeli officials have privately indicated that they think the program has slowed. In 2009, Israeli Mossad chief Meir Dagan said that it would probably take Iran until 2014 before it could produce a functional nuclear weapon.

What this adds up to is the sense that the United States and its allies have some time, probably several years—but not forever. Which is why we can afford to try a policy of pressure. But we need to make sure that we apply it with real determination, ratcheting up the heat on Iran more than the administration has done thus far. The key is to take on a range of new activities that the White House has mostly resisted.

AN EFFECTIVE strategy will need to be harsher, more varied and more sustainable than our current course of action. The United States needs to make Iran a true pariah state, and one squeezed enough from both outside and inside that it eventually recognizes it would be better to make some concessions than continue under the strain.

First, we must expand the focus of the pressure: from ire at the nuclear program to ire at Iran’s abuse of human rights. There are lots of countries that abuse human rights, and the Iranians will doubtless claim a double standard. But the past thirty years have demonstrated that the world is actually quite comfortable with double standards, harshly punishing some human-rights abusers while ignoring others. This is not to condone such hypocrisy, only to point out that it should not be seen as a practical obstacle to pressing the Iranian regime for its increasingly authoritarian behavior. The United States need not wait until every nation with a worse human-rights record has reformed itself to point out that Iran’s has become egregious, and to mobilize international opinion to hold the regime accountable. The existence of a worse crime should not excuse a very bad one.

Since Iran’s recent disputed presidential election, I have had the opportunity to speak to a range of Iranians in permissive environments. On every one of those occasions, I have asked them how the United States could help the Iranian opposition, and what I have consistently heard from them is that Washington needs to sanction Tehran, not for its pursuit of a nuclear-enrichment capability, but because of its abuse of human rights. They argue that the current leaders are very sensitive to any criticism of their record because they believe that it delegitimizes them in the eyes of many of the people—as it actually has done. The administration’s September decision to impose sanctions on eight senior Iranian officials for their role in Iran’s internal crackdown was a terrific start, but it falls far short of what is needed. Calling Iran to account for its deplorable abuses in this arena is likely to strike a much-more-responsive note with a number of other states around the world—even those whose own histories are far from spotless. Many other third-world countries resent the great-power monopoly over nuclear weapons (and so sympathize with Iran’s nuclear ambitions), but very few will condone gross, systematic human-rights violations. Indeed, the European Left, which was once made up of avid Iran apologists, has now largely turned against the regime, incensed by its brutal crackdowns.

Although Iran and apartheid South Africa have little in common, the human-rights campaign that eventually succeeded in forcing the white South African government to dismantle its odious system could serve as a useful model. Various nations and human-rights organizations kept up a steady drumbeat, exposing abuses with concomitant condemnation. Over time, it became impossible for businesses and even countries (including governments that could not have cared less about human rights) to have normal relations with Pretoria. The stigma simply became too great. And just as in South Africa, human rights could become an important vehicle to galvanize international support to choke off investment in Iran and perhaps provide some much-needed relief to the Iranian opposition by making it more painful for the regime to suppress them with violence.

This expanded effort needs to be coupled with a more tenable sanctions regime than the one now in effect. Sanctions cannot be the only means by which the United States and its allies pressure Iran to change its behavior, but as one necessary part of the strategy, they need to work better—and for longer.

We need to remember the lessons of our unsuccessful effort to do the same to Saddam Hussein’s Iraq. In 1991, the United Nations imposed strict sanctions on the country, expecting that this would force Saddam to comply with its demands in a matter of months (145 days, to be precise). The problem was that Saddam refused to back down, and the United States and its allies were then forced to attempt to hold to those draconian measures for a dozen years in a vain attempt at compellence. By 2003, the sanctions were in shambles. Saddam and his trading partners were flouting the few remaining prohibitions that the UN had not yet repealed. This is because the sanctions were unsustainable: the Iraqis found ways around the financial controls, and the trade restrictions allowed the regime to starve large segments of its population and then claim that it was the sanctions that were responsible for hundreds of thousands of deaths. Trade sanctions inevitably inflict hardship on average people—which the international community will find impossible to stomach for long. Washington should beware this type of coercion.

The kinds of sanctions that tend to work best over time instead focus on cutting off foreign investment in the targeted country. No one dies from such a loss, so it is much easier to sustain. Here as well, South Africa provides a useful analogy. The human-rights-based campaign against apartheid focused on slowly choking off direct foreign investment in South Africa. The “divestment” campaigns, coupled with state and business actions, squeezed South Africa’s GDP, but not in a way that caused severe, direct harm to the vast majority of South Africans. Instead, what the efforts did was paint an unmistakable picture for the South African leadership that if they did not change, their country would be reduced to a poor, isolated pariah state—North Korea with elephants—and that was simply intolerable. Given Iranian pretensions to world-power status, a similar perspective might have equally palliative effects.

If the systematic choking off of investment to Iran’s economy is coupled with clandestine efforts to destabilize the regime and its nuclear ambitions, we may just have a workable strategy. First, the obvious. Washington ought to be mounting a full-court press to try to sabotage the Iranian nuclear program. Israel seems to have been hard at work on this for decades, and there is talk that the United States has as well. One can only hope that, in this case, the rumors are true. Successful sabotage operations, both physical and cyber, will slow down the program, giving all the other aspects of the pressure campaign a greater chance of having an impact.

But more important is the ultimate goal of putting at risk the current leadership’s hold on power. For many Americans, “covert action” is nothing but a four-letter word. It is certainly the case that covert-action campaigns can backfire badly, as the United States has learned to its chagrin at a wide variety of times and in a wide variety of places—including in Iran more than once. But this history should serve as a warning, not a prohibition. Turning up the pressure on Iran’s hard-liners is going to be very difficult as it is; the United States should not unilaterally eschew an option that could be helpful just because it too will be hard to get right. The question is whether specific operations have a high-enough probability of success, a low-enough probability that failure would cause serious harm, and a reasonable expectation that even partial success would be significantly useful.

It seems highly unlikely that the CIA could help usher in the sort of regime change in Iran that it did in 1953. But the United States can and should do more to help the opposition. It would be irresponsible for Washington to bet its Iran policy on engineering a second revolution; still, support ought to be an element of a new American strategy—even if it is not the primary focus. Indeed, instead of wasting our time on far-fetched notions of toppling the regime altogether, the United States and its allies ought to be working overtime to try to discover what they could do to help the Green movement, rather than discrediting it with the Iranian people and encouraging even-harsher crackdowns from the regime.

America’s covert actions against Iran need not stop there. The Green movement is the biggest and most liberal opposition movement, but it is not the only one. There are Kurdish, Baluch, Arab and other groups fighting those in power, and Washington should consider supporting any and all of them. If nothing else, they can certainly help turn up the heat by attacking the government’s security forces and diminishing the regime’s fearful reputation and control over the countryside. Moreover, since Tehran is convinced that the United States is doing this already, there would appear to be little further downside to fulfilling Iran’s paranoid suspicions, at least in terms of the leadership’s response.

But while we isolate, constrict and undermine the regime, we must ever allow for the possibility of a peaceful reconciliation. Obama administration officials like to say that they will always “leave the door open” for Iran to indicate that it wants a better relationship. They say they are ready to sit down and negotiate an end to all the animosity. It’s a good line—and a good policy.

The whole point of a policy of pressure is to convince Iran to give up its nuclear ambitions and its efforts to overturn the Middle Eastern status quo by supporting terrorists and other violent groups. That requires being willing to take “yes” for an answer from Tehran, and always giving the Iranian regime the chance to cry, “Enough!” There’s nothing to be lost from regularly reiterating that the United States would prefer a cooperative resolution of our differences. In fact, there is a lot to be gained. The rest of the world will be far more willing to support the United States against Iran if Washington’s efforts at pressure are taken with a measure of sorrow, rather than anger. Then, perhaps the rest of the world won’t fear that the United States is looking for any excuse to invade another Middle Eastern country whose government it doesn’t particularly like. To this end, it would also be helpful for the administration to more loudly and fully enumerate what it is prepared to do to benefit Iran if the leadership was willing to halt its nuclear program, its support for terrorists and its efforts to destabilize Southwest Asia.

IN THE end, all this may fail. With its hard-liners firmly in charge, Tehran may choose further suffering, isolation and weakness rather than give up its nuclear program. If so, the United States will then face a choice between military operations and a containment strategy meant to limit or prevent a nuclear Iran from making mischief beyond its borders until the regime finally collapses from its own dysfunctions.

Containment always gets a bad rap in American policy debates, but it is an approach that has served us well in the past. The United States successfully contained the Soviet Union as well as a host of lesser countries—Cuba, North Korea, Nicaragua, Libya, Iraq (less successfully) and Iran itself since the revolution. Part of the reason that Americans dislike containment is that it is always the last-ditch approach: when a country does not want to have good relations with us, but we aren’t willing to invade and can’t find a way to overthrow the regime, we contain it until the government falls, changes its ways or some other opportunity comes along.

Yet this doesn’t have to be a passive strategy in which the United States does little more than play defense and wait. Containment can be very confrontational or very cooperative, very aggressive or very passive. Our policy toward the USSR ranged from rollback to flexible response to détente. Our containment of Iraq featured draconian sanctions backed up by a blockade, frequent air strikes, sabotage, and support to a wide range of attempted coups, insurgents and opposition groups.

If a policy approach that combines an expanded mandate of isolation, pressure and support to opposition groups does fail to persuade Iran to halt its nuclear program, it will still create the foundation for an extremely robust, if not highly aggressive, containment strategy. That may prove critically important over the long term, as it will help us avoid our bad habit of refusing to consider containment until our other, preferred policies all fail catastrophically and we are forced to quickly cobble together a containment regime from whatever is left at hand. Let us still hope, however, that it proves extremely useful long before that.

Ironically, because the current Iranian regime is betting that it can outlast the sanctions, one thing that might make Tehran reconsider its current course when all else fails would be a concerted effort by the United States and the international community to build an aggressive new containment regime that Iran cannot possibly outlast. Like North Korea, Iran would not be allowed to enjoy any benefit from its acquisition of a nuclear capability or even a nuclear arsenal. It would face a situation where it was left weaker, poorer, more isolated and more diminished by its pursuit of nuclear weapons. Perhaps that might be a sobering-enough thought to convince the ruling elite to change course. It would be only fitting that the puzzling Iranian regime would ultimately be persuaded to cease its pursuit of a nuclear capability by an international policy built around the premise that Iran could not be persuaded to do so.

Kenneth M. Pollack, a contributing editor to The National Interest, is director of the Saban Center for Middle East Policy at the Brookings Institution and the lead author of Which Path to Persia? Options for a New American Strategy Toward Iran (Brookings Institution Press, 2009).

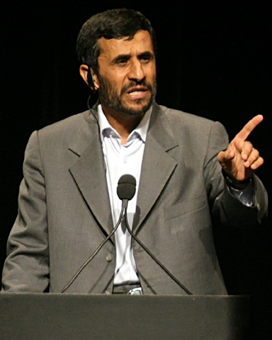

(Photo by Daniella Zalcman)

Image: Pullquote: The United States needs to make Iran a true pariah state, and one squeezed enough from both outside and inside that it eventually recognizes it would be better to make some concessions than continue under the strain.Essay Types: Essay

Pullquote: The United States needs to make Iran a true pariah state, and one squeezed enough from both outside and inside that it eventually recognizes it would be better to make some concessions than continue under the strain.Essay Types: Essay