When Kerry Stormed D.C.

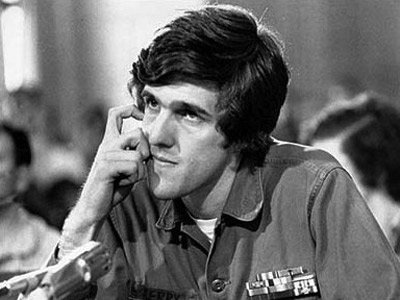

Mini Teaser: John Kerry was just five years out of Yale when he testified before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee and became an instant celebrity.

These are commanders who have deserted their troops, and there is no more serious crime in the law of war. The Army says they never leave their wounded. The Marines say they never leave even their dead. These men have left all the casualties and retreated behind a pious shield of public rectitude.

The senators did not move. The reporters tried to look unmoved. The room was very silent. Only the cameras hummed politely as they recorded Kerry’s testimony for later broadcast to the nation.

In conclusion, Kerry accused “this administration” of paying the veterans the “ultimate dishonor.” He said, “They have attempted to disown us and the sacrifice we made for this country. In their blindness and fear they have tried to deny that we are veterans or that we served in Nam. We do not need their testimony. Our own scars and stumps of limbs are witnesses enough for others and for ourselves.”

And then, more in sadness than artificial pomp, though maybe a bit of both, since Kerry was an accomplished orator, he finished with these words:

We wish that a merciful God could wipe away our own memories of that service as easily as this administration has wiped their memories of us. But all that they have done and all that they can do by this denial is to make more clear than ever our own determination to undertake one last mission, to search out and destroy the last vestige of this barbaric war, to pacify our own hearts, to conquer the hate and the fear that have driven this country these last 10 years and more, and so when, in 30 years from now, our brothers go down the street without a leg, without an arm, or a face, and small boys ask why, we will be able to say “Vietnam” and not mean a desert, not a filthy obscene memory but mean instead the place where America finally turned and where soldiers like us helped it in the turning.

The room, which had been still, erupted in applause and cheers. The Vietnam Veterans Against the War (VVAW), the organization Kerry was representing, had finally been heard, not just on Capitol Hill but in time across the nation. Outside, among the veterans gathered on the Washington Mall, small groups formed around transistor radios, listening to Kerry’s critique. Many got down on one knee, raising their right fists to the sky. American flags were unfurled. One could even see a number of Vietcong banners. On the fringes, there were other flags: “Quakers for Peace” and “Hard Hats Against the War.” One veteran, who had lost both legs, sat in a wheelchair—he too raised his fist to the sky. He had fought his last war.

CHAIRMAN J. William Fulbright, a Democrat from Arkansas, who had helped steer the Tonkin Gulf resolution through Congress in August 1964, providing the “legal” authority for American military action in Vietnam, but who later became an active critic of the war, praised Kerry for his eloquence and his message and asked whether he was familiar with the antiwar resolutions then under discussion and debate in Congress. Fulbright said that a number of committee members had advanced resolutions to end the war, “seeking the most practical way that we can find and, I believe, to do it at the earliest opportunity that we can.” Kerry responded that his veterans would like to end the war “immediately and unilaterally.” Based on his talks with the North Vietnamese in Paris, Kerry believed, naively as it turned out, that if the United States “set a date . . . the earliest possible date” for its withdrawal from Vietnam, the North Vietnamese would then release American prisoners of war. What we later learned was that the North Vietnamese had other plans. Kerry added that he didn’t “mean to sound pessimistic,” but he really didn’t think “this Congress” would end the war by legislation.

Senators known for their volubility sat speechless.

“You have a Silver Star; have you not?” injected Senator Stuart Symington of Missouri. A Silver Star was the army’s third-highest award for valor.

“Yes, I do,” Kerry responded.

“You have a Purple Heart?” Symington continued.

“Yes, I do.”

“How many clusters on it?”

“Two clusters.”

“You were wounded three times?”

“Yes, sir.”

“I have no further questions,” Symington concluded.

Other senators asked other questions, but they were mostly in the form of compliments and congratulations—they were not probing for substantive information.

Fulbright and Kerry were obviously reading from the same sheet of antiwar music. The two had met at a reception honoring the VVAW held at the home of Senator Phil Hart of Michigan, and Fulbright liked Kerry’s style. He was, according to historian Douglas Brinkley, “very impressed by Kerry’s polite . . . demeanor. He was not a screamer. He didn’t look disheveled.” The next morning a Fulbright staffer called Kerry. “We want you to testify,” he said. Happily, Kerry agreed, even though he knew he did not have enough time to prepare properly. With Adam Walinsky, a former aide to both John and Robert Kennedy, at his side, Kerry spent the whole night writing and rewriting his testimony, while balancing other responsibilities as one of the principal coordinators of the five-day demonstration.

Around 9:30 a.m., Thursday, April 22, 1971, a friend, reporter Tom Oliphant of the Boston Globe, found Kerry at a meeting at a demonstration on the Hill. “Do you realize what time it is?” he asked. “Shouldn’t we get going?” Kerry checked his watch. “Oh, my God,” he said. “Let’s go.” With Oliphant, he set off at a brisk pace down Independence Avenue toward the Dirksen Senate Office Building. As they passed the Supreme Court, Kerry noticed an angry group of veterans on the top steps of the building. He then did what he had been doing all week. “Up he went, and once again, you know, the hand on the arm, the talking them down.” Oliphant heard Kerry say: “We don’t want any sideshows. Please help.” Kerry always worried about image—about whether the veterans, many of them looking like Woodstock hippies, were making a positive impression on the American people.

By then, it was “six or seven minutes” to the start of the hearing. “Uh, John,” Oliphant said, pulling on his sleeve, “you might want to go testify before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee.” Kerry broke away from the protesting veterans. The two rushed off to room 4221. “We got to the door, and I actually opened it,” Oliphant remembered, “and he started to go towards it, at which point he pulled back like somebody had punched him, just went back like this, and said, ‘Oh shit!’” Kerry had just caught his first glimpse of the crowded, noisy conference room. He suddenly realized he was entering the big leagues of national politics.

Oliphant continued:

The room was completely jammed. There was a full spread of television cameras, completely filled press tables, the most prestigious committee in the entire United States Congress, to see a twenty-seven-year-old in combat fatigues make a statement about the Vietnam War. The response, not just inside the hearing room, but nationally—it was electric, and it was immediate. This person and that message had gone national in the blink of an eye.

AT THE White House, which had anxiously observed the antiwar demonstration all week and done everything in its power to contain and downplay it, President Nixon met with his chief of staff, H. R. Haldeman, to consider other steps they could take against the antiwar veterans. Neither could ignore the impact of Kerry’s testimony. They had decided early on that the Nixon administration would have no contact with these veterans. No official would be allowed to talk to them or to receive them at the White House, the Pentagon or the State Department. They had even refused to grant permission to five “Gold Star Mothers” to enter Arlington National Cemetery to lay two wreaths at gravesites for Asian and American soldiers. The next morning, seeing the negative play in the media, they changed their minds and allowed a few of the “Mothers” to enter. The administration also withheld permission for the veterans to camp on the Washington Mall, but three remarkable things then happened: the courts imposed a ban on Mall camping, the veterans simply ignored it and the Washington police did nothing to enforce it.

Before both Nixon and Haldeman were reports of media coverage of Kerry and the veterans, which was extensive and for the most part favorable. According to the official audiotape of their conversation, both were impressed by Kerry’s performance, and both realized that it only made their job harder. They were still responsible for prosecuting a war and for running a country that was quickly losing confidence in their leadership.

Nixon: “Apparently, this fellow, uh, that they put in the front row, is, that you say, the front, according to [White House aide Patrick] Buchanan . . . ‘the real star was Kerry.’”

Image: Pullquote: From 1972, when he ran unsuccessfully for Congress, until 2004, when he ran unsuccessfully for president of the United States, Kerry’s world was intimately entangled with Vietnam.Essay Types: Essay

Pullquote: From 1972, when he ran unsuccessfully for Congress, until 2004, when he ran unsuccessfully for president of the United States, Kerry’s world was intimately entangled with Vietnam.Essay Types: Essay