America's Boys in Blue: Battledress Revolutionary War

Unlike the soldier of the modern era, who has specially made packs and a plethora of equipment, the Continental Army soldier basically headed into battle with his uniform, weapon and little else.

Today’s Army Service Uniform, which is the military uniform worn by the United States Army personnel in situations where formal dress is called for, including workday situations, has returned to the “greens and pinks” retro look of the Second World War, yet it has its roots in the “army blue” uniform that harkens back to the Revolutionary War. Yet, during the earliest days of the American Revolution—before independence was even declared—the uniforms worn by the American colonial forces differed greatly and weren't even originally slated to be blue.

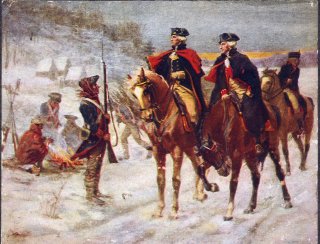

When the Continental Army was established the soldiers had no actual uniforms. In 1775, the Continental Congress adopted brown, not blue, as the official color for the uniforms. This was already a popular color with the New England Provincials. Various regiments were distinguished by different color collars, cuffs and lapels; while the cut of the coat was similar to the British, albeit plainer. The plan under General George Washington was to have the Continental Army all in uniform by the beginning of 1776, but this was only partially successful.

After a few months of campaigning the earliest uniforms were already worn out; while there were also shortages of brown cloth. As a result, many regiments used the colors of blue or gray instead. This increased when in the spring of 1778 a shipment of blue coats arrived from France. This may have influenced Washington's decision to issue a General Order that formed the basis for the first American dress regulations. The infantry were to be clothed in dark blue with different facings and distinctions to denote the states from which the soldier came. White facing was used for New England, red for the Mid-Atlantic, blue for the south. Musicians wore uniform coats in reverse color, however.

This European style military dress was in scarce supply, but American hunting dress—the type worn by frontiersmen in Pennsylvania and Virginia, and which derived from Indian clothing—was used as a supplementary solution. Washington had some 10,000 sets furnished to the army.

Revolutionary War Headdress

Military fashion in the era generally followed styles embedded in civilian society and this is seen in the cocked hats or tricorn hats that were worn by the major powers, including the Continental Army. There were attempts at military elitism, where field officers attached red or pink cockades to their hats, while captains displayed cockades in yellow or black. There were several different styles of the tricorn hats, but typically these were worn with the front corner directly over the left eye—and this was done to avoid a conflict while carrying the musket.

While popular the tricorn hat was not the only headdress worn by the Continental Army—despite Hollywood misconceptions that would suggest otherwise. Another style of headgear that was popular was the “liberty cap,” which was a wool knit cap that would be rolled over the ears in the winter. Contemporary illustrations suggest it was common to have the words “Congress” or “Liberty or Death” embroidered on the front.

Cavalry units followed other European traditions and wore helmets made of either leather or brass, but this generally depended upon available supply. The American dragoon pattern helmets were inspired—likely even supplied—by the French. This dragoon helmet could thus be considered the first true American combat helmet.

Small Arms of the Continental Army

The American small arms industry was barely in its infancy during the Revolutionary War, and as a result, most American soldiers carried smoothbore flintlock muskets including the British “Brown Bess” as well as French-made muskets. As the war progressed the colonial forces obtained Dutch and even Prussian muskets. While this supplied the Army and ensured that the men could be armed this also resulted in many different types and size calibers. There were efforts to standardize the muskets by regiments, but even by war's end it was anything but a standard affair.

The American Continental Army also made some use of rifles, which were only introduced in the colonies circa 1700 by German and Swiss emigrants. These long guns had greater range and were more accurate than the smoothbore muskets, but these took about three times as long to load, and were prone to being put out of action in bad weather. Moreover, the rifles of the era lacked a bayonet. Riflemen, therefore, could neither stand nor charge in the line of battle, and as a result, the rifle was essentially removed from general service by 1781.

Flintlock pistols were used primarily for personal purposes—and were much like private purchase sidearms used in later conflicts, so many officers and men of higher stature carried these as an extra weapon. The accuracy of pistols was not good, and most had an effective range of less than 20 feet, while the loading time was still limited to just two or three rounds a minute.

Officers up to and including carried swords and/or espontoons (half pikes), while most soldiers—apart from riflemen—relied on the bayonet in combat. Due to the differing sizes of the calibers of the muskets the bayonets had to be practically tailor-made to the particular firearm!

Equipment of the Continental Army

Unlike the soldier of the modern era, who has specially made packs and a plethora of equipment, the Continental Army soldier basically headed into battle with his uniform, weapon and little else. Each soldier carried about thirty rounds made up into cartridges ahead of battle, and these were held in waterproof leather cartouche boxes that also held a musket tool and supply of flints. Powder pouches and cow horns were also used.

In addition, each soldier also carried a haversack, usually made of linen to carry food rations and eating utensils that include a fork, knife, spoon, plate and cut. Soldiers were equipped with a canteen that was made of wood, tin, or glass. Additional items included flint and steel for starting a fire, candle holders, a comb, mirror, and razor for shaving.

Peter Suciu is a Michigan-based writer who has contributed to more than four dozen magazines, newspapers, and websites. He is the author of several books on military headgear including A Gallery of Military Headdress, which is available on Amazon.com.