Coronavirus Is Awful. The Black Death Killed Nearly Half of Europe.

It was hell on earth if you caught it.

The modern world is unaccustomed to public health crises. We live in an era that eliminated smallpox, can treat cancer, and has made HIV into a condition that is treatable and no longer a death sentence.

That is why the coronavirus pandemic has shaken so many in their confidence about modern medicine and faith in the security of their society. The panic, the uncertainty, and even the isolation are small cases of what has come before, in the form of Europe’s worst disease outbreak in its history.

What became known as the Black Death was an outbreak of plague that infested Europe from 1347 to 1351. Originating, like the coronavirus, in the East, it was carried in the form of fleas on the backs of rats on trading ships, and eventually spread to the entire western continent. It is estimated that the plague killed half of Europe’s population, perhaps as many as one hundred million people.

Giovanni Boccaccio was an Italian writer living in the city of Florence, and his firsthand account of the Black Death is considered the best of the period. His descriptions of both the horror of the disease and the corresponding human behavior resemble how people are being affected in the here and now.

Boccaccio described the means that Florence took to keep out the disease, including travel bans and the recommendation of personal hygiene, both of which were attempted and failed to stop the coronavirus outbreak in the United States. “There, spite of all the means that art and human foresight could suggest, such as keeping the city clear from filth, the exclusion of all suspected persons, and the publication of copious instructions for the preservation of health, and notwithstanding manifold humble supplications offered to God in processions and otherwise,” the Black Death still arrived in Florence.

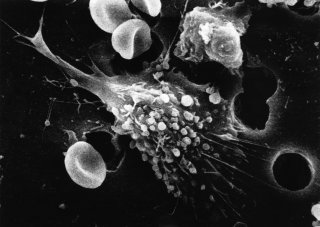

The author described the symptoms of the plague in grotesque detail. “[T]here appeared certain tumors in the groin or under the arm-pits, some as big as a small apple, others as an egg; and afterwards purple spots in most parts of the body; in some cases large and but few in number, in others smaller and more numerous—both sorts the usual messengers of death,” he wrote in 1348.

“These facts, and others of the like sort, occasioned various fears and devices amongst those who survived, all tending to the same uncharitable and cruel end; which was, to avoid the sick and everything that had been near them, expecting by that means to save themselves.,” Boccaccio wrote, the results of which are reminiscent of how Americans are coping with social distancing today. People “made parties and shut themselves up from the rest of the world; eating and drinking moderately of the best and diverting themselves with music and such other entertainments as they might have within doors; never listening to anything from without to make them uneasy.”

Furthermore, this destruction of the public atmosphere led to a complete loss of civic virtue and trust in governing institutions. “And such, at that time, was the public distress that the laws, human and divine, were no more regarded; for the officers, to put them in force, being either dead, sick, or in want of persons to assist them, everyone did just as he pleased,” Boccaccio said.

For the masses of peasants and serfs who survived the Black Death, their allotment in life was able to marginally improve. The apocalyptic severing in half of the labor market caused wages to increase for those left alive, and there was more land to share among them. But it would take two centuries before Europe recovered from the population loss.

Hunter DeRensis is a senior reporter for the National Interest. Follow him on Twitter @HunterDeRensis.