France and Britain's Cold War: The Race to Zero Emissions

They have the same target: carbon neutrality by 2050.

The long-running rivalry between France and Britain has entered a new era: who will decarbonise the fastest. As the UK government announced on June 11 that it had committed to a net zero emissions target for 2050, the French parliament is currently working on a draft energy and climate bill that has the same target for 2050.

In both cases, the net zero objective ramps up earlier targets. In France, it would replace one set by a 2015 energy transition law, which targeted a 75% cut in greenhouse-gas emissions by 2050 compared to 1990 levels. In the UK, net zero for 2050 replaces a previous target of an 80% reduction over the same period; it was introduced in the law on June 12. The increased ambition is the result of advice from the UK’s Committee on Climate Change (CCC), the country’s independent advisory body.

France and the UK are the largest countries so far to set such an ambitious objective in legislation. Sweden, Denmark and Norway have already adopted the legal objective of carbon neutrality, but with the use of international emissions-trading mechanisms.

The French project and the recommendation of the CCC in UK do not include this type of mechanism, although the UK government announced it reserves the right to use credits. Other countries – such as Ethiopia, Costa Rica, Bhutan, Fiji Islands, Iceland, Marshall Islands and Portugal – have also announced plans for carbon neutrality by 2050 in strategic documents but without legislative scope.

The 2018 report of the IPCC indicates that to stabilise global warming at 1.5°C, net emissions at the global scale must reach zero by 2050; and by 2070 for 2°C.

Emissions of other greenhouse gases must also be significantly reduced to maintain these trajectories. The CCC report also shows that neutrality of “all greenhouse gases” by 2070 is compatible with the 1.5°C trajectory. This means that the 2050 net zero emissions goal for all greenhouse gases is more ambitious than the global trajectory compatible with 1.5°C warming.

Comparing emissions on both sides of the Channel

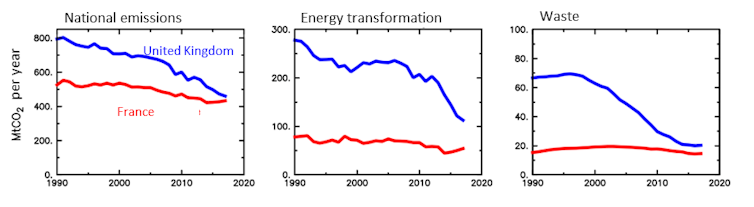

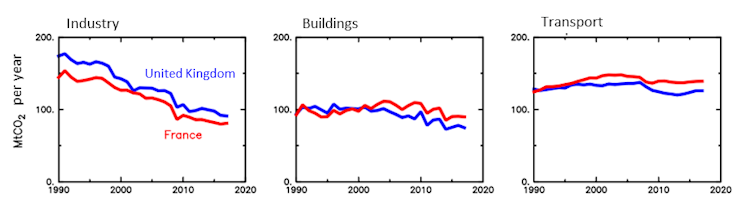

France and the United Kingdom share many characteristics. They have similar populations, comparable levels of development and their territorial greenhouse-gas emissions are similar – 7 tCO₂ per inhabitant for the United Kingdom and 6.7 tCO₂ per inhabitant for France in 2017.

Emission trajectories since 1990 have been decreasing overall, with a larger decrease for the UK from a higher level in 1990. This is mostly due to the transition away from coal-fired power plants for electricity, as well as a significant catch-up in waste management.

Emissions from the industrial sector are decreasing significantly and similarly in both countries. According to CCC’s analysis, this decline in the United Kingdom can be explained by changes in economic structure, improved energy efficiency and a reduction in the carbon intensity of the energy mix.

Emissions from the building sector have declined over the past 10 years in both countries, with larger decreases in the United Kingdom. In contrast, emissions from the transport sector have stagnated in both countries, with a slight decrease in the United Kingdom and an increase in France since 1990.

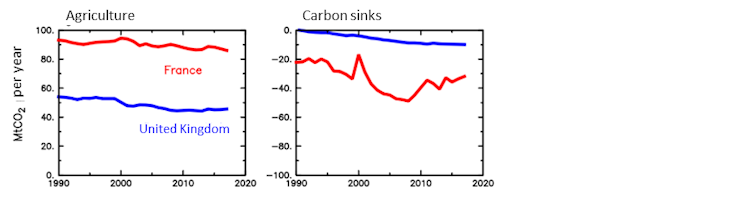

However, important differences exist in agriculture and carbon sinks. Agriculture is economically more important in France, emitting twice as much carbon much as in the United Kingdom. Carbon sinks, which are largely based on the increase in carbon stored in forests, are also more significant in France. Emissions reduction in both sectors are comparable.

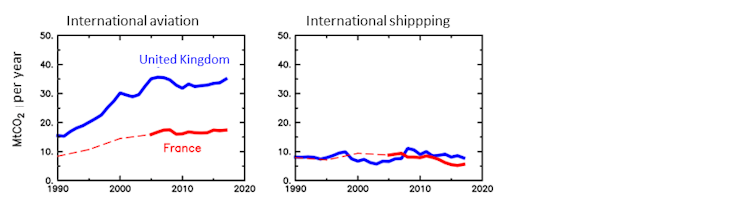

One important difference concerns emissions from international transport. Aviation and maritime transport emissions are not included in the reporting to the United Nations under the Paris Agreement. The UK’s net zero objective includes these emissions, while France’s current draft energy bill does not.

If the other sectors follow the projected reduction pathways, emissions from aviation, which are relatively low for the time being, will be responsible for the majority of remaining emissions in 2050. They will therefore have to be offset by carbon sinks or other CO2 extraction mechanisms, requiring a significant increase in the number of sinks (see figure below, based on data from the United Kingdomand France).

“Hidden” emissions

In their 2050 net zero objectives, France and the United Kingdom do not include so-called “imported” emissions – those associated with consuming products and services from abroad.

Including these imported emissions, the carbon footprints of both nations reach 11 tCO₂/inhabitant/year for France and 11.9 tCO₂/inhabitant/year for the United Kingdom.

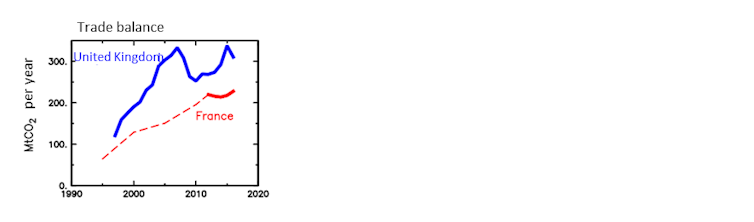

After accounting for products consumed abroad (“exported” emissions), emissions from the trade balance are very high and have risen since the mid-1990s (see figure opposite) with a possible slowdown since 2005 in the United Kingdom and since 2011 in France. These emissions are difficult to control, they are nevertheless the responsibility of consumers.

While France’s draft energy and climate law states that these emissions must be controlled, it gives no quantitative targets. In the UK, the CCC recommendation is that these emissions should decline in response to certain efficiency measures, but recognizes that these emissions can only be reduced to zero when global emissions reach this threshold.

Time is running out

The United Kingdom has managed to rapidly reduce its emissions over the past decade, which are now close to the French level. This rapid decrease was recommended and monitored by the Committee on Climate Change, which has prioritized the decarbonisation of electricity production that underlies that of other sectors. Today, both countries are at a point where emissions must decrease rapidly in the coming decades to reach their net zero targets by 2050.

A shared challenge is initiating and accelerating the transition in sectors that are tough to decarbonise because, compared with the energy sector, emissions are more diffuse – particularly transport and buildings.

The Haut Conseil pour le Climat, of which we are both members, was created in late 2018 and directly inspired by the UK CCC. There is no magic policy package that will lead nations to net zero emissions in 2050. The UK example demonstrates, and France acknowledges, the need for an independent advisory group that is focused on the long-term to support and guide the transition in the coming decades.

The French Haut Conseil will assess the implementation of France’s national low-carbon strategy and propose course corrections where necessary, while taking into account the socio-economic impacts of the transition on households and businesses as well as environmental impacts. Its first report will be made public on June 25.

Céline Guivarch is part of the team of authors of the 6th IPCC report. She is a member of the French High Council for Climate Change. Céline Guivarch has received funding from the European Commission, the Ministry of Ecological and Solidarity Transition, the French Environment and Energy Management Agency, the French Environment and Energy Management Agency, the International Energy Agency, the World Bank, EDF, Renault, the "Modélisation prospective pour le développement durable" chair and the Institut pour la mobilité durable. It is a member of the "Weather and Climate" association.

Corinne Le Quéré is President of the High Council for Climate Change. For her research on the carbon cycle, she has received funding from the European Commission, the Royal Society of the United Kingdom, the Natural Environment Research Council (UK).

Their article first appeared in The Conversation in June 2019.

Image: Reuters.